AP Syllabus focus:

“During World War I, restrictions on speech increased as fears of radicalism produced a Red Scare and attacks on labor activism and immigrant culture.”

Wartime fears, government action, and social tensions converged during World War I, sharply limiting civil liberties while escalating anxieties about radicalism and igniting the nation’s first Red Scare.

Civil Liberties Under Strain in World War I

Federal efforts to mobilize national unity against external threats during World War I reshaped American political culture. The government increasingly linked dissent with disloyalty, creating a climate in which restrictions on speech, surveillance, and prosecutions expanded dramatically. The state justified these measures as necessary to maintain wartime morale and protect national security, yet their implementation revealed deep anxieties about domestic radicalism and perceived threats from immigrants, labor unions, and political movements on the left.

Federal Legislation Limiting Expression

To suppress dissent, Congress enacted laws that empowered the federal government to punish perceived antiwar activity.

The Espionage Act of 1917 criminalized interference with military operations and prohibited attempts to cause insubordination within the armed forces.

The Sedition Act of 1918 expanded these powers by banning “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive” language about the government or the war effort.

Espionage Act of 1917: A federal law enabling prosecution of individuals who obstructed military recruitment or supported America’s enemies during wartime.

These laws signaled a dramatic expansion of federal authority over public expression, bringing thousands of Americans—journalists, pacifists, labor organizers, and socialists—under investigation or indictment.

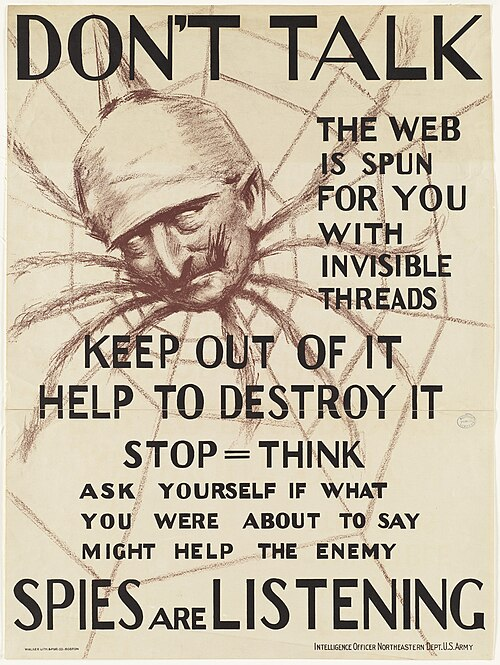

This World War I propaganda poster warns against careless speech by depicting the German Kaiser as a spider weaving a dangerous web. The dramatic imagery reflects efforts to link ordinary conversation with national security risks. Although visually heightened beyond syllabus requirements, it demonstrates how public fear helped justify wartime limits on civil liberties. Source.

The Supreme Court upheld these laws in cases such as Schenck v. United States (1919), famously invoking the “clear and present danger” standard to justify limits on civil liberties during wartime.

A nationwide climate of vigilance encouraged organizations such as the American Protective League to assist federal agencies by monitoring communities, workplaces, and immigrant neighborhoods for questionable activities. The government’s reliance on volunteer surveillance blurred boundaries between state authority and local suspicion, fostering an environment of coercion and intimidation.

Radicalism and Wartime Anxieties

Public fears intensified as labor unrest, ideological conflict, and international upheaval converged. Many Americans interpreted strikes and union activism as signs of radical influence, particularly after the 1917 Russian Revolution, which heightened anxieties about Bolshevism, a term broadly applied—often inaccurately—to labor organizers and immigrant activists.

Labor Activism as a Target

Labor disruptions during and immediately after the war appeared threatening to industries considered vital to national security. Several factors contributed to heightened suspicion:

Wartime production methods strained workers with long hours and rising costs of living.

Major strikes in industries such as steel and coal were publicly framed as attempts to sabotage the war effort or destabilize the economy.

Immigrant workers, who made up large portions of the industrial labor force, were often blamed for importing radical ideologies.

Bolshevism: A revolutionary ideology associated with the Russian Revolution, commonly invoked in the United States to describe perceived radical threats, regardless of accuracy.

Accusations of disloyalty weakened unions’ bargaining power and encouraged both employers and government officials to equate collective action with subversion.

The First Red Scare

The Red Scare of 1919–1920 grew from these wartime anxieties, transforming temporary security measures into a broader campaign against alleged radical infiltration. As bombings, strikes, and political unrest erupted across the country, government agencies intensified surveillance and repression.

The Palmer Raids

Under Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, the Justice Department—assisted by J. Edgar Hoover and the young Bureau of Investigation—conducted mass arrests and deportations targeting suspected radicals.

Key features included:

Warrantless raids on meeting halls and private homes

Seizure of records from labor and socialist organizations

Detention of thousands of individuals, many of whom lacked formal charges

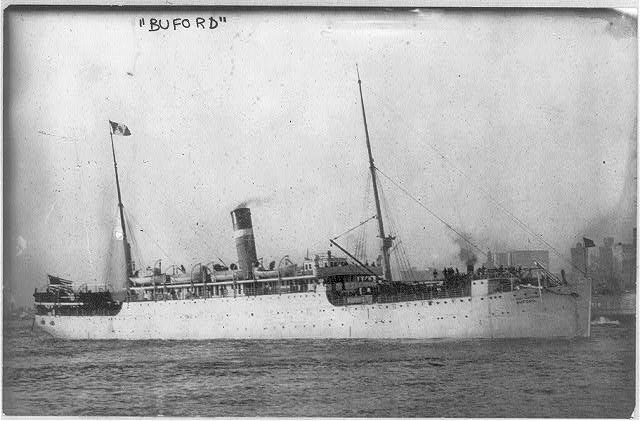

Deportation of immigrant activists, such as those aboard the so-called “Soviet Ark”

This photograph shows the U.S. transport Buford, the vessel used to deport hundreds of alleged radicals during the Palmer Raids. Its role in transporting detainees abroad illustrates how deportation became a major tool of the early Red Scare. The photograph focuses on the ship rather than individual deportees, offering a structural view of state power in this period. Source.

These actions tested constitutional limits and generated significant debate. Critics argued that Palmer’s methods violated due process and represented an abandonment of American principles, while supporters viewed them as essential to national security during a moment of perceived crisis.

Attacks on Immigrant Culture and Ideological Diversity

Fears of radicalism heightened existing nativist sentiment. Immigrant communities—especially those from Eastern and Southern Europe—were often portrayed as inherently prone to radical thought.

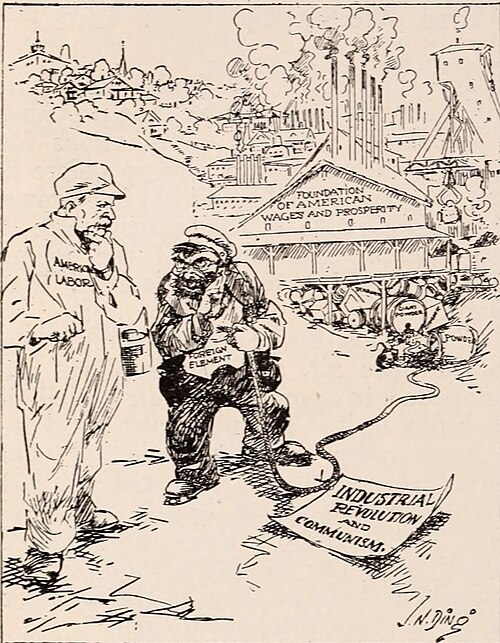

This period cartoon depicts exaggerated fears of foreign radicals, illustrating how wartime suspicion fueled xenophobia. Its publication in a mainstream employee magazine shows how anti-immigrant messaging circulated widely. Although it includes surrounding contextual text not covered in the syllabus, it effectively conveys public anxieties about immigrant political activity. Source.

Consequences included:

Censorship of foreign-language newspapers

Pressure on schools to eliminate non-English instruction

Discrimination against immigrants in employment and public life

These developments reinforced the belief that American identity required cultural conformity, linking patriotism to assimilation and political orthodoxy.

Civil Liberties in Retrospect

Although many wartime restrictions faded after 1920, the era left a lasting imprint on American political culture. The broad suppression of speech, the conflation of dissent with disloyalty, and the distrust of immigrant communities established precedents for future conflicts over civil liberties.

FAQ

Local police forces and city governments often enforced federal wartime laws aggressively, sometimes exceeding their intended scope.

Many cities passed their own loyalty ordinances, enabling arrests for refusing to salute the flag or criticising wartime measures.

Vigilante groups, such as hometown “loyalty leagues,” collaborated informally with law enforcement, conducting surveillance and intimidating dissenters without formal oversight.

Unions were associated with collective action at a time when the government equated unity with patriotism.

Their demands for higher wages and better conditions during wartime production were framed as disruptive or un-American.

Union members often included Eastern and Southern European immigrants, making ethnic prejudice and political suspicion mutually reinforcing.

Newspapers frequently amplified fears of radical infiltration.

Headlines highlighted bomb plots, strikes, and arrests, often with little verification, reinforcing the idea that radicals threatened national stability.

Sensationalist reporting gave legitimacy to government crackdowns by portraying repression as necessary self-defence against internal enemies.

Public anxiety after a series of bombings and labour unrest made decisive action appear necessary.

Attorney General Palmer presented the raids as protective measures against a looming revolutionary threat.

For many citizens, the promise of restoring order outweighed concerns about due process or civil liberties.

Suspicion of immigrant political loyalties fuelled campaigns promoting cultural uniformity.

Schools emphasised English-only instruction as a marker of loyalty.

Community organisations pressured immigrants to abandon native-language publications, clubs, and traditions, equating assimilation with patriotism.

These efforts reflected the belief that cultural difference could mask radical sympathies.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which the United States government restricted civil liberties during World War I and explain briefly how this restriction related to fears of radicalism.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a specific restriction on civil liberties (e.g., Espionage Act, Sedition Act, surveillance by the American Protective League).

1 mark for describing how this restriction operated (e.g., criminalising dissent, prosecuting anti-war speech, monitoring immigrant communities).

1 mark for linking the restriction to fears of radicalism, disloyalty, or wartime subversion.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which fears of radicalism shaped government action during the First Red Scare (1919–1920).

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

Up to 2 marks for describing the historical context of the First Red Scare (e.g., post-war strikes, Russian Revolution, bomb scares).

Up to 2 marks for explaining specific government actions driven by fears of radicalism (e.g., Palmer Raids, mass arrests, deportations aboard the “Soviet Ark”).

Up to 1 mark for evaluating the extent of this influence (e.g., distinguishing between genuine security concerns and political opportunism, discussing the scale of civil liberties violations).

Up to 1 mark for supporting the argument with accurate, relevant evidence from the period.