AP Syllabus focus:

‘By 1920, most Americans lived in urban centers that offered new economic opportunities for women, international immigrants, and internal migrants.’

Urban America in the 1920s transformed daily life and expanded opportunities for diverse groups as cities became hubs of industry, culture, and social change, reshaping American society.

Expanding Urbanization and Demographic Change

The early twentieth century witnessed a major shift from a predominantly rural society to one centered on urban industrial growth. By 1920, the U.S. Census confirmed that most Americans lived in urban areas, reflecting nationwide reliance on wage labor and mass production.

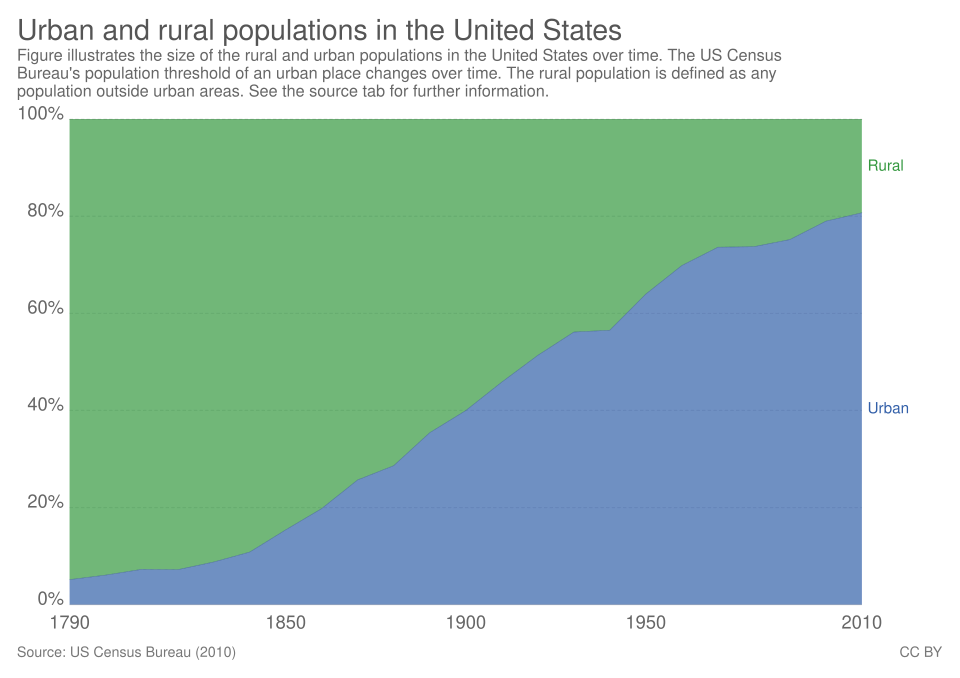

Urban and rural population trends in the United States from 1790 to 2010. The chart shows the gradual rise of the urban share and decline of the rural share, with the transition point around 1920 when the nation became majority urban. The image includes later years for context beyond the syllabus period. Source.

Cities drew millions of Americans seeking better wages, independence, and community life. Industrial centers such as Chicago, New York, Detroit, and Philadelphia became magnets for people leaving rural regions. Migrants pursued jobs in steel, automotive, and consumer-goods factories, where mass production methods expanded hiring needs.

High wages compared to agricultural income

Greater access to public amenities and transportation

Diverse neighborhoods that supported social mobility

The migration included rural white Southerners, African Americans participating in the Great Migration, and young adults seeking alternatives to agricultural labor. These movements contributed to a new, heterogeneous urban population.

International Immigration and Urban Settlement

International immigration, especially from southern and eastern Europe, profoundly shaped urban growth. Immigrants often settled in ethnic neighborhoods—Little Italys, Chinatowns, and Jewish districts—where cultural networks eased adaptation.

Mulberry Street in New York City around 1900 illustrates the vibrancy of immigrant ethnic neighborhoods. The dense street markets and tenement housing reflect how immigrants created supportive communities while adapting to urban life. The image focuses on one Italian district, offering additional specificity beyond broad national patterns. Source.

Ethnic Enclave: A neighborhood dominated by a particular immigrant or cultural group, offering social networks, familiar customs, and community institutions.

Immigrant communities forged strong cultural ties through churches, mutual-aid societies, and newspapers, while also navigating pressures to assimilate into American culture.

New Opportunities for Women in Urban America

Urbanization opened new pathways for women’s economic and social participation. Cities created labor markets beyond domestic service, expanding roles in clerical work, retail, and manufacturing.

Women working in a typing pool demonstrate the expanding clerical workforce of the early 20th century. Urban business centers required extensive office labor, providing new wage-earning opportunities for women. Though taken in 1931, the image accurately represents the office settings already emerging in the 1920s. Source.

Women and the Modern Workforce

The rise of department stores, offices, and communication industries broadened employment options. Women now worked as:

Typists and stenographers

Telephone operators

Retail clerks

Assembly-line workers

These positions supported financial independence and increased visibility in public life. Opportunities still varied by race and class; white middle-class women often gained access to office and service positions, while working-class and minority women remained concentrated in manufacturing or domestic labor.

A more modern, urban womanhood emerged, shaped by mass culture and new expectations. Clothing styles, leisure activities, and professional ambitions reflected changing norms regarding gender.

Social Mobility and Cultural Transformation

Urban centers facilitated encounters among migrants, immigrants, and longtime residents. These interactions generated both cultural flowering and social tensions.

Neighborhood Life and Community Institutions

Cities were dense environments in which distinctive communities developed educational, religious, and cultural institutions. These spaces created support systems for newcomers and helped define urban identity.

Settlement houses provided language training, job assistance, and childcare.

Churches and synagogues preserved traditions while promoting social mobility.

Newspapers and theaters supported cultural continuity.

Settlement houses were especially active among immigrant families adapting to industrial society.

Settlement House: A community-based reform institution offering social services, education, and welfare programs to immigrants and the urban poor.

These institutions linked social reform to lived experience, reflecting broader Progressive Era concerns about poverty, public health, and community well-being.

Economic Structure and Urban Labor Markets

Urban labor systems evolved rapidly as mass production reshaped employment and required new forms of worker organization. The 1920s economy emphasized consumer goods, automobiles, and communication technologies, each supported by specialized labor.

Opportunities and Challenges in Labor

Although cities generated wealth and employment, conditions varied widely:

Many workers earned steady wages and participated in consumer culture.

Others faced dangerous workplaces, long hours, or discriminatory hiring practices.

Women and immigrants often received lower wages than white male workers.

These inequalities highlighted the limitations of urban opportunity and fueled debates about economic justice.

Social Tensions and Cultural Adjustment

The rapid influx of migrants and immigrants produced cultural complexity and social friction. Native-born Americans sometimes viewed changing demographics with suspicion, contributing to nativism and calls for immigration restriction. These tensions intersected with debates about religion, modernity, and cultural identity throughout the decade.

Navigating Urban Modernity

Urban life required adaptation to crowded housing, diverse languages, and rapid technological change. Yet cities also fostered vibrant arts, music, and entertainment scenes. They were central to the emergence of a shared national culture, shaped by radio, cinema, and advertising, though not fully addressed within this subsubtopic. Urban opportunities thus represented both economic advancement and cultural transformation for millions of Americans in the early twentieth century.

FAQ

Many newcomers encountered overcrowded tenements, where poor ventilation and limited sanitation created health risks. These conditions were often the result of rapid population growth outpacing urban infrastructure.

Some families adapted by taking in lodgers, sharing costs, and relying on neighbourhood networks. Others moved frequently in search of safer or more affordable accommodation, reinforcing the instability many migrants experienced upon arriving in urban centres.

Electric streetcars and expanding bus routes allowed workers to live farther from factories and offices, widening access to employment beyond immediate neighbourhoods.

These transport networks also encouraged the development of commercial districts, where shops and offices concentrated around major transit routes. This helped to create new service-sector jobs and contributed to a more mobile and connected urban workforce.

Cities brought together people of different nationalities, languages, and customs, creating environments unfamiliar to many rural Americans. Some feared that such diversity would dilute established cultural norms or challenge existing social hierarchies.

This anxiety contributed to stereotyping and social boundaries, influencing debates over immigration restriction and American identity during the period.

Urban residents gained access to new forms of entertainment linked to commercial culture. These included amusement parks, dance halls, cinemas, and sporting events.

Working-class youths frequented inexpensive venues near industrial districts.

Middle-class residents often engaged in more regulated leisure, such as museums or organised clubs.

The variety of choices reflected the dynamic social environment of growing cities.

City governments struggled to provide adequate services, such as waste removal, clean water, fire protection, and policing. Growth often outpaced public budgets and administrative capacity.

Corruption and political machines sometimes filled gaps by offering informal assistance but demanded voter loyalty in return. These pressures pushed many reformers to seek more professional, efficient urban governance.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which urbanisation in the early twentieth century created new opportunities for women in the United States.

Mark scheme

1 mark: Identifies an appropriate opportunity (e.g., clerical work, retail employment).

2 marks: Provides a clear explanation of how urbanisation made this opportunity possible (e.g., expansion of offices and department stores).

3 marks: Develops the explanation with specific historical detail (e.g., growing need for typists and telephone operators as businesses expanded).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which immigration contributed to the transformation of urban life in the United States by the 1920s.

Mark scheme

1–2 marks: Provides a basic description of immigrant presence in cities.

3–4 marks: Offers a developed explanation of ways immigrants shaped urban culture, labour markets, and neighbourhood structure (e.g., ethnic enclaves, industrial labour).

5–6 marks: Presents a well-supported evaluation addressing both the extent of immigrant influence and other contributing factors (e.g., internal migration, industrialisation), demonstrating analytical judgement.