AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the 1920s, Americans clashed over gender roles, modernism, science, religion, and issues tied to race and immigration.’

The 1920s witnessed fierce cultural conflict as Americans confronted rapid social change, negotiating tensions between tradition and innovation across religion, science, gender, race, and national identity.

Culture Wars in a Decade of Transformation

The decade’s social upheaval reflected broader struggles over what it meant to be “American.” Economic growth, urbanization, mass immigration, and technological change created new cultural landscapes. These shifts intensified debate between modernists—who embraced scientific inquiry, cultural experimentation, and evolving social norms—and traditionalists, who defended established religious beliefs, moral values, and racial hierarchies.

Religion, Science, and the Modernist–Fundamentalist Divide

At the center of the era’s cultural divisions was a conflict between modernist and fundamentalist interpretations of Christianity. Modernists sought to reconcile faith with scientific understandings, including evolutionary theory and higher biblical criticism. Fundamentalists rejected these developments, insisting on the literal truth of scripture and viewing modernism as a moral and spiritual threat.

One of the most emblematic episodes was the Scopes Trial of 1925, in which a Tennessee schoolteacher, John Scopes, was prosecuted for teaching evolution.

Outdoor court proceedings during the 1925 Scopes Trial show defense attorney Clarence Darrow interrogating prosecutor William Jennings Bryan. The scene illustrates how a local dispute over teaching evolution became a national showdown between modernist science and fundamentalist religion. The large audience and reporters highlight how intensely Americans followed this cultural conflict. Source.

Although the trial ended in Scopes’s conviction, the intense national media attention demonstrated how deeply Americans disagreed over the authority of science and religion.

These disputes shaped broader political debates, including efforts to regulate public education and resist perceived moral decline in urban culture.

Gender Roles, Sexuality, and Social Morality

Rapid cultural change challenged traditional expectations for women. The emergence of the “New Woman” reflected growing female independence, visible through increased participation in the workforce, consumer culture, and public life. Women’s suffrage, secured through the Nineteenth Amendment, expanded political engagement. Meanwhile, changing fashion, social behavior, and attitudes toward sexuality provoked criticism from conservative Americans concerned about weakening family structures.

The flapper, a young woman who embraced shorter hemlines, bobbed hair, and assertive social freedoms, became a powerful cultural symbol.

This photograph of Mlle. Rae highlights typical flapper style—shorter skirt, bobbed hair, and a garter flask suggesting defiance of Prohibition-era respectability. Her confident stance reflects changing gender norms and growing female autonomy. The additional detail related to nightlife extends beyond the syllabus but helps contextualize anxieties about cultural change. Source.

Flapper: A cultural icon of the 1920s representing young women who challenged traditional norms through fashion, behavior, and greater personal autonomy.

Disputes over gender roles also intersected with debates about birth control, marriage, and family stability. Reformers such as Margaret Sanger advocated broader access to contraception, arguing that reproductive control was essential to women’s autonomy. Critics condemned these efforts as immoral, linking them to fears of cultural decline and shifting gender expectations.

Race, Immigration, and the Politics of Exclusion

Racial tensions intensified in the 1920s as African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans continued to face structural discrimination and violence. At the same time, massive internal and international migrations reshaped cities, fueling cultural creativity but also backlash. Many white Americans, especially in rural and small-town areas, viewed demographic change as destabilizing established racial hierarchies.

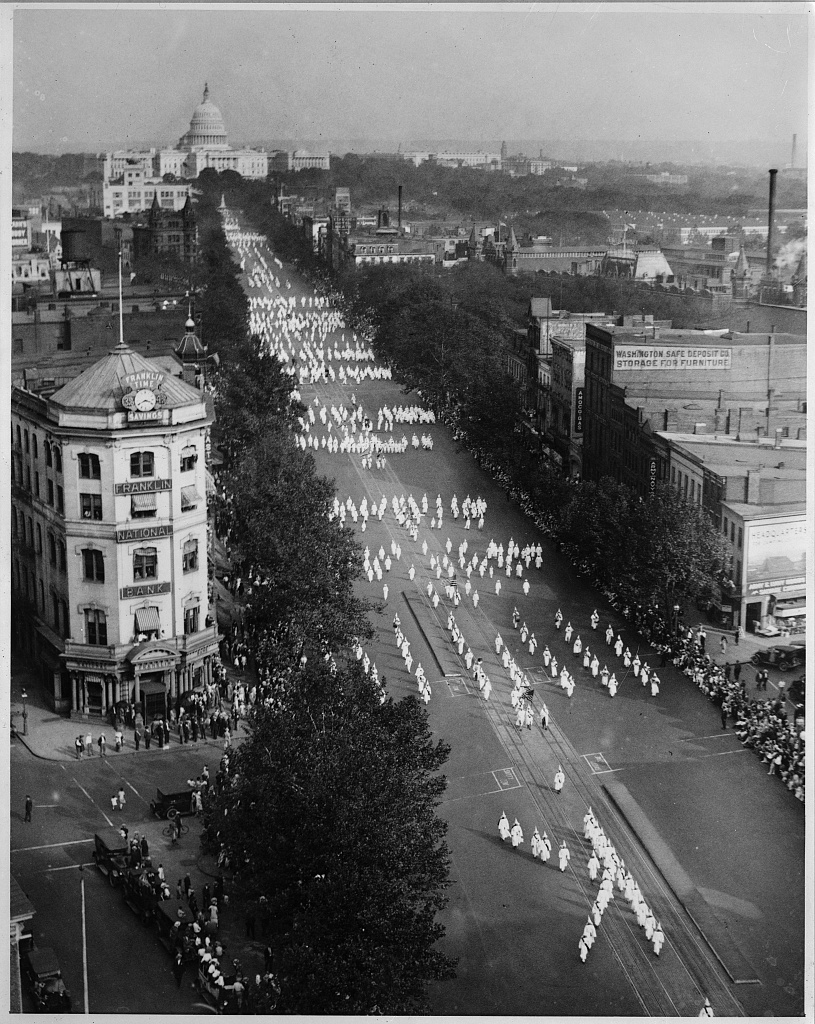

These anxieties contributed to the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, which expanded its influence nationwide by presenting itself as a defender of “100 percent Americanism.”

A 1926 Ku Klux Klan parade marches down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the U.S. Capitol, demonstrating the organization’s national visibility and influence. The image reflects how the Klan promoted white Protestant supremacy and nativism during the decade. Architectural details extend beyond the syllabus but illustrate how public and mainstream these displays became. Source.

The Klan targeted African Americans, Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and anyone viewed as deviating from traditional Protestant norms. Its growth reflected widespread racial and religious nativism, even as civil rights organizations such as the NAACP sought to fight segregation, lynching, and discrimination.

Immigration debates further revealed deep cultural divisions. Nativist groups argued that newcomers from southern and eastern Europe threatened American identity and were incapable of assimilating due to supposed racial and cultural differences. Their activism helped produce restrictive federal laws.

Nativism: The belief that immigration should be limited to protect the cultural, economic, or political interests of native-born Americans.

The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924 established numerical quotas that sharply reduced immigration and heavily favored northern and western European nations. These policies institutionalized racial and ethnic hierarchy in federal law and reflected broader fears of radicalism, cultural change, and economic competition.

Meanwhile, Asian immigration faced near-total exclusion, reinforcing long-standing discriminatory policies.

Cultural Expression and Conflict

The period’s cultural conflicts also unfolded through art, literature, and mass entertainment. The Harlem Renaissance showcased the creative achievements of African American writers, musicians, and thinkers, who used cultural expression to articulate modern Black identity and challenge racism. Their work confronted stereotypes and highlighted the contradictions between American democratic ideals and ongoing racial injustice.

At the same time, new mass media—especially radio and film—created shared national experiences that could unify but also divide Americans. While some embraced these technologies as reflections of modern dynamism, others feared they encouraged immorality, secularism, and the erosion of local traditions.

Persistent Tensions in a Changing Society

By the end of the 1920s, the culture wars over modernism, religion, race, and gender had reshaped national politics and identity. These conflicts did not resolve the nation’s underlying divisions; rather, they exposed enduring debates about American values, authority, and belonging that would continue into subsequent decades.

FAQ

Rural communities tended to resist modernist ideas, viewing urban cultural change as a threat to traditional morality and religious authority.

Urban areas, by contrast, were more exposed to new technologies, diverse populations, and scientific debate, making them more receptive to modernist thought. These regional differences intensified national cultural conflict.

Public schools became a battleground for defining national values. Debates over whether evolution should be taught reflected fears that modern science would undermine religious belief.

• State legislatures passed anti-evolution laws to protect traditional morality.

• Educators and reformers argued that scientific literacy was essential in a modern society.

The struggle highlighted competing visions of citizenship and intellectual authority.

Flappers symbolised challenges to long-standing gender norms, particularly in behaviour, fashion, and autonomy.

They represented:

• Greater social freedom for young women

• Willingness to reject Victorian moral codes

• Participation in consumer culture and nightlife

Conservatives saw this as a sign of moral decline and a breakdown of family stability, intensifying cultural anxiety.

The Klan framed itself as a defender of Protestant Christian values, claiming that immigration, urbanisation, and changing social norms threatened the nation’s spiritual purity.

It used religious rhetoric to portray Catholics, Jews, and immigrants as dangers to American identity. This allowed the organisation to broaden its appeal beyond the South and operate nationwide.

Supporters of restriction argued that the United States should preserve a cultural identity rooted in northern and western European heritage.

They believed newer immigrants from southern and eastern Europe brought radical political ideas or were culturally incompatible.

Opponents argued that such views contradicted American ideals of opportunity and pluralism. The debate revealed deep uncertainty about who counted as “truly” American.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Scopes Trial reflected broader cultural tensions in the United States during the 1920s.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Offers a general statement about cultural tensions without clear connection to the Scopes Trial.

(e.g., “There were disagreements about modern ideas in the 1920s.”)

2 marks:

• Demonstrates a clear link between the Scopes Trial and a broader cultural divide (e.g., religion vs. science, rural vs. urban values) with some explanation.

3 marks:

• Provides a developed explanation showing how the Scopes Trial symbolised major national divisions, such as fundamentalism vs. modernism, conflict over educational authority, or fears of moral decline, with explicit contextual detail from the 1920s.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how debates over gender roles and race shaped cultural conflict in the United States during the 1920s. In your answer, refer to specific groups and developments of the decade.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Identifies at least one example of gender-related conflict (e.g., the flapper, debates over sexuality or birth control) and one example of race-related conflict (e.g., Ku Klux Klan revival, immigration restriction) with basic explanation.

• Demonstrates some understanding of how these issues contributed to cultural tensions.

5 marks:

• Provides clear and accurate analysis of how debates over gender and race shaped cultural conflict, with relevant specific detail (such as the behaviour and symbolism of flappers, or the Klan’s promotion of “100 per cent Americanism”).

• Shows how these debates reflected wider struggles over American identity.

6 marks:

• Offers a well-structured and nuanced analysis linking gender and race issues to the broader phenomenon of 1920s culture wars.

• Uses specific evidence (e.g., Margaret Sanger, Immigration Act of 1924, national visibility of the Klan) to demonstrate significance.

• May comment on the interaction of gender and racial anxieties or how these conflicts shaped national politics and social attitudes.