AP Syllabus focus:

‘Civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., fought racial discrimination using legal challenges, direct action, and nonviolent protest.’

The Strategic Foundations of Direct Action

Direct action emerged as a deliberate tactic to expose the injustice of segregation and force political, legal, and economic responses. Rooted in Gandhian nonviolence and Christian ethics, these methods relied on public confrontation without physical retaliation, allowing activists to highlight oppressive systems in real time.

Philosophy of Nonviolent Resistance

Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. emphasized that nonviolence required not only peaceful behavior but also active engagement with systems of oppression. Activists sought to dramatize inequality and provoke negotiation by enduring arrest, violence, and public scrutiny.

Nonviolent Resistance: A method of social change in which participants confront injustice through peaceful actions designed to highlight oppression and pressure institutions to alter discriminatory policies.

Nonviolent direct action differed from legal strategies because it attempted to create immediate crisis conditions. These campaigns aimed to make segregation untenable by disrupting daily routines and attracting national attention.

Student Activism and the Birth of Sit-Ins

A pivotal development was the rise of student-led activism, which broadened participation and accelerated the pace of change. Sit-ins began in 1960 when four Black students challenged a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Their quiet refusal to leave after being denied service sparked widespread emulation.

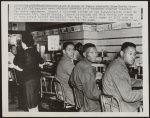

This photograph shows three African American students staging a sit-in at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro in 1960, illustrating the peaceful discipline of the sit-in movement. Their calm presence dramatized the injustice of segregated public facilities and helped inspire similar actions across the South. The photo includes surrounding bystanders and counter details not explicitly described in the notes but remains fully relevant to the event. Source.

Tactics and Expansion

Sit-ins rapidly spread across southern cities due to their simplicity and high visibility. Participants prepared for violent backlash through training in nonviolent discipline, ensuring that maintaining moral high ground remained central.

Key elements of sit-in campaigns included:

Physical occupation of segregated public spaces

Refusal to retaliate despite harassment or assault

Mass arrests that strained local legal systems

Boycotts supporting protest efforts and pressuring businesses economically

These actions motivated the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which formalized youth activism and coordinated regional campaigns.

Freedom Rides and Interstate Transportation

After early sit-in successes, activists turned toward segregation in interstate travel. The Freedom Rides of 1961 tested federal court rulings that banned segregation in bus terminals.

This image depicts Freedom Riders at the Birmingham Greyhound station in 1961 as they prepared to challenge segregated interstate facilities. Their presence demonstrates the disciplined courage required for nonviolent direct action under threat of mob violence. The photo reflects the environment activists entered, though it includes background architectural details not discussed in the notes. Source.

Challenges and Federal Response

Freedom Riders faced severe violence, including bus bombings and mob attacks, especially in Alabama. Their persistence forced the Kennedy administration to act, resulting in new federal regulations enforcing desegregation in interstate facilities.

Interstate Commerce: Economic or travel activity crossing state boundaries and thus falling under federal regulatory authority.

These campaigns demonstrated how direct action could compel federal intervention by revealing gaps between constitutional rulings and local practices.

Birmingham and the National Spotlight

In 1963, Birmingham, Alabama—one of the most segregated cities in the South—became the stage for a major nonviolent campaign. Led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and King, the movement combined marches, sit-ins, and selective boycotts designed to put pressure on the city’s political and economic structures.

Project C (Confrontation)

The Birmingham movement’s strategy included:

Coordinated actions across multiple segregation targets

Mass arrests, including King himself

Youth participation, especially in the Children’s Crusade

Media visibility that captured violent police responses

Images of police dogs and fire hoses used against peaceful demonstrators shocked the nation and helped accelerate support for federal civil rights legislation. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” articulated the moral and strategic foundations of nonviolent direct action, defending its necessity against critics who urged patience.

The March on Washington and Movement Cohesion

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963 showcased the national reach of nonviolent protest.

This photograph captures the immense crowd gathered for the 1963 March on Washington, illustrating the scale and unity of the nonviolent demonstration. The image reinforces how peaceful mass mobilization became a powerful force in the civil rights movement. It includes broader scene details, such as the Reflecting Pool and surrounding landscape, extending slightly beyond the scope of the notes while remaining fully relevant. Source.

Bringing over 200,000 participants to the capital, the march emphasized economic justice, civil rights legislation, and racial unity.

Coordinating a National Demonstration

Although large and diverse, the march maintained disciplined nonviolence. It highlighted:

The broad coalition of civil rights organizations

The importance of federal action for civil rights protections

Public support generated by peaceful, integrated mass gatherings

This event amplified King’s message and demonstrated the movement’s ability to operate on a national scale.

The Power and Limits of Nonviolent Protest

Direct action successfully exposed the brutality of segregation, mobilized widespread participation, and pressured federal authorities. Its strengths included moral clarity, media resonance, and the ability to disrupt discriminatory systems. However, activists also confronted limitations: entrenched local resistance, internal debates over strategy, and the physical danger faced by participants.

Still, the period’s nonviolent campaigns decisively shaped public opinion and laid essential groundwork for landmark legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

FAQ

Preparation involved structured workshops, often run by groups like the Fellowship of Reconciliation or the Nashville Student Movement. These sessions trained volunteers to remain calm under verbal or physical assault.

Participants practised scenarios involving harassment, arrest, and intimidation.

Training also reinforced dress standards, body language, and the discipline required to maintain moral authority during demonstrations.

Students often held fewer economic or family obligations, making them more able to risk expulsion, arrest, or job loss. They were also heavily influenced by campus networks, including church groups and activist societies.

The moral clarity and energy of young people helped accelerate the spread of sit-ins and sustain participation in intense campaigns like the Freedom Rides.

Local residents provided logistical and emotional support, which was essential for prolonged action.

Support included:

Hosting out-of-town activists

Providing transport to court hearings or demonstrations

Donating food, legal aid funds, and communication networks

Their involvement ensured campaigns could continue even when national organisations had limited resources.

Authorities often used bureaucratic tactics such as enforcing obscure local ordinances, manipulating permit rules, or imposing excessive bail fees.

Economic retaliation was also common. Businesses fired employees who participated in protests, and landlords threatened eviction to discourage activism.

These strategies sought to erode momentum while avoiding the national backlash triggered by overt brutality.

Television and photojournalism amplified the visibility of local struggles, transforming otherwise isolated incidents into national concerns.

Images of dignified, peaceful demonstrators contrasted sharply with abusive responses from segregationists, shifting public opinion.

News reports also increased federal pressure to intervene, as political leaders could no longer ignore widespread evidence of civil rights violations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one specific tactic used by civil rights activists during direct action campaigns in the early 1960s and explain how it supported the strategy of nonviolent protest.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for correctly identifying a tactic (e.g., sit-ins, Freedom Rides, selective boycotts, nonviolent training, mass arrests).

1 mark for explaining how this tactic exposed segregation, provoked public attention, or highlighted injustice.

1 mark for linking the tactic explicitly to the broader strategy of nonviolence (e.g., demonstrating moral authority, refusing retaliation, forcing negotiation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how direct action and nonviolent protest between 1960 and 1963 helped shift national attitudes and federal responses to racial segregation. In your answer, refer to at least two specific campaigns.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks as follows:

Up to 2 marks for accurate description of at least two campaigns (e.g., Greensboro sit-ins, Freedom Rides, Birmingham Campaign, March on Washington).

Up to 2 marks for explaining how these campaigns shaped national attitudes, such as increasing media visibility, generating public sympathy, or exposing violence of segregationists.

Up to 2 marks for explaining how federal responses changed, such as the Kennedy administration enforcing interstate desegregation, increased support for civil rights legislation, or greater willingness to intervene.

High-level responses will:

Connect nonviolent strategy to its political effects.

Offer specific and accurate historical detail.