AP Syllabus focus:

‘After 1965, disagreements over nonviolence and strategy grew, reflecting new approaches to achieving racial justice and community control.’

Shifting Contexts After 1965

The passage of major federal civil rights legislation altered the political landscape but did not eliminate structural racism, economic inequality, or police brutality. Many African Americans, especially in northern and western cities, felt that nonviolent protest had achieved legal change without addressing deeper social and economic injustices. These frustrations, combined with rising urban unrest and disillusionment with federal responsiveness, encouraged activists to explore alternative strategies for achieving racial justice beyond traditional civil rights approaches.

Declining Consensus Around Nonviolence

Nonviolence, once the dominant framework for civil rights activism, came under increasing scrutiny after 1965. Some activists argued that nonviolent protest placed moral burdens on Black communities without compelling meaningful concessions from governmental authorities. Others maintained that nonviolence remained essential for broad-based coalitions and public sympathy.

These tensions created space for new ideological currents, including Black Power, which emphasised autonomy, dignity, and self-determination.

The Emergence of Black Power

Black Power emerged as both a political slogan and an ideological framework challenging the gradualism and integrationist goals of earlier civil rights strategies. It reflected a desire for greater control over Black communities, resources, and institutions.

Black Power: A movement and philosophy advocating racial pride, economic independence, community control, and, in some interpretations, self-defence as alternatives or complements to traditional civil rights strategies.

Origins and Meaning

The term gained national prominence when Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture), then a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), used it during the 1966 Meredith March Against Fear.

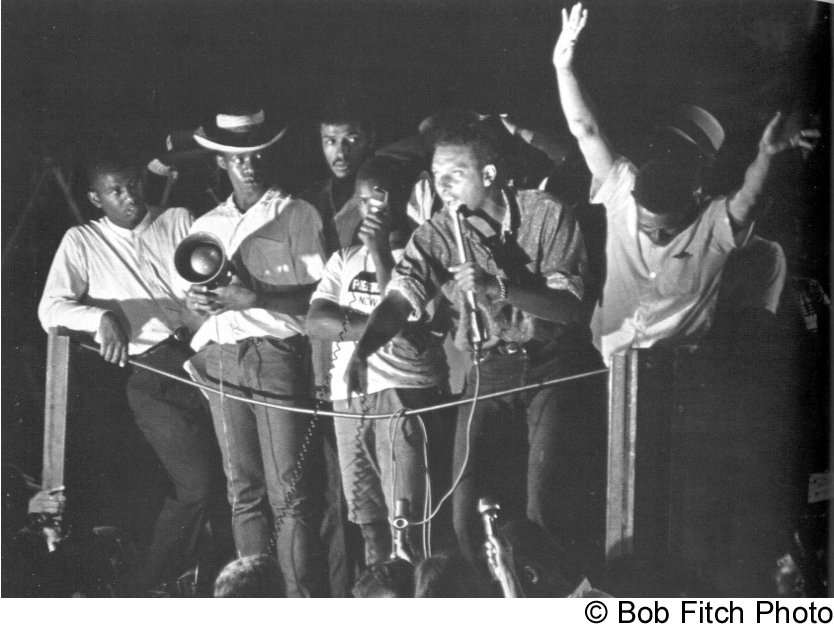

This photograph captures Stokely Carmichael introducing the call for “Black Power” during the Meredith March Against Fear. His speech symbolised the shift toward self-determination and frustration with gradualist strategies. The image also includes additional contextual detail from the broader march not covered directly in the notes. Source.

Although its meanings varied, Black Power generally called for:

Strengthening Black political and economic institutions

Rejecting paternalistic or token integration

Promoting cultural pride

Supporting self-defence in the face of violence

These perspectives resonated with many younger activists who had become frustrated with persistent inequality and slow progress.

Organisational Change and Strategic Divisions

The rise of Black Power reshaped major civil rights organisations. SNCC, once committed to interracial nonviolence, increasingly embraced separatist ideas, limiting white participation. This shift reflected growing distrust of federal institutions and scepticism about whether interracial cooperation could achieve meaningful reforms.

Tensions Within the Movement

Differences emerged over several key issues:

Integration vs. autonomy: Whether Black communities should prioritise working within existing systems or building independent structures

Nonviolence vs. self-defence: Whether armed self-protection was legitimate in the face of police brutality and white supremacist violence

Leadership models: Debates over charismatic, centralised leadership versus grassroots, community-driven structures

These disagreements did not signal the collapse of the movement but revealed its increasing ideological diversity.

The Black Panther Party and Community-Based Approaches

One of the most influential expressions of Black Power was the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, founded in Oakland, California, in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. Contrary to popular perception, the Panthers were not solely focused on armed patrols but developed extensive community programmes.

Community Survival Programmes

Among the Panthers’ most notable initiatives were:

This image shows a member of the Black Panther Party serving breakfast to schoolchildren, illustrating the Party’s community survival work. These programmes reflected Black Power’s emphasis on practical support, autonomy, and local control. The article also discusses later federal responses, which exceed syllabus requirements but offer broader historical context. Source.

Free Breakfast for Children initiatives

Health clinics providing medical care and screening

Political education classes

Legal aid and community support services

These programmes aimed to build self-sufficiency and demonstrate how community control could address unmet needs.

Confrontation with Law Enforcement

The Panthers’ armed police patrols, designed to monitor police behaviour and assert constitutional rights, heightened tensions with local and federal authorities. Their visibility and assertiveness made them targets of surveillance and disruption by the FBI’s COINTELPRO programme.

COINTELPRO: A covert FBI initiative aimed at infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting political organisations deemed subversive, including Black Power groups.

Federal repression intensified internal organisational strains and contributed to the decline of the Panthers by the early 1970s.

Cultural Nationalism and the Politics of Identity

Alongside political activism, the Black Power era saw a flourishing of Black cultural nationalism, which celebrated African heritage, promoted pride in Black identity, and challenged dominant cultural norms.

This photograph of the Wall of Respect mural highlights the cultural expression central to Black Power. Artists used public space to celebrate Black identity and honour community heroes. Although the image includes wider Black Arts Movement themes beyond the syllabus, it directly supports discussions of cultural nationalism in the notes. Source.

Influence on Education, Arts, and Community Life

Black Power transformed cultural expression through:

Rising interest in African-inspired art, clothing, and names

Development of Black Studies programmes at universities

Expansion of independent Black media and publishing

Greater emphasis on community-controlled schools

These cultural shifts helped redefine what liberation meant beyond legal equality, linking personal identity with broader struggles for autonomy.

Broader Impact on Civil Rights Debates

The emergence of Black Power pushed national conversations about racial justice into new territory. While some Americans perceived the movement as confrontational, others saw it as a necessary response to structural inequality and unfulfilled promises of earlier reforms.

Continuing Debates

Disagreements after 1965 centred on:

How quickly and radically American institutions should change

Whether integration or independence offered the most effective path to equality

The role of federal institutions in protecting Black communities

The legitimacy of armed self-defence in contexts of systemic violence

These debates reflected an evolving movement adapting to new conditions, expanding the meanings and methods of African American activism in the late 1960s and beyond.

FAQ

Many younger activists lived in segregated urban neighbourhoods where discrimination in housing, policing, and employment remained severe despite civil rights legislation.

Their daily encounters with economic inequality and police harassment led them to doubt that nonviolence or integrationist strategies could address the conditions facing their communities.

Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. worried that militant language would alienate moderate white supporters and undermine bipartisan support for federal reforms.

They also believed that an emphasis on separatism risked fragmenting a movement that had relied on interracial cooperation for national influence.

Black Power thinkers drew inspiration from anti-colonial movements in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

They saw parallels between global struggles for independence and the fight for self-determination within the United States, which reinforced arguments for autonomy and resistance to state oppression.

Key points of tension included:

Growing frustration with federal inaction in the South

Disputes over whether white activists should participate in Black-led groups

Differing responses to state violence and police repression

These disagreements highlighted contrasting visions for how to achieve racial justice.

Activists believed that reclaiming African heritage and affirming Black identity were essential to resisting cultural domination.

Cultural nationalism also provided accessible tools—art, language, education, fashion—through which ordinary people could participate in the movement, strengthening community cohesion and pride.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one goal of the Black Power movement after 1965 and briefly explain how it differed from earlier civil rights strategies.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid goal (e.g., community control, cultural pride, economic independence, self-defence, political autonomy).

1 mark for explaining how this goal reflected new priorities or frustrations.

1 mark for contrasting it accurately with earlier strategies, such as integrationism or nonviolent protest.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the ways in which debates over nonviolence, self-defence, and community control reshaped the civil rights movement after 1965. In your answer, refer to specific groups or leaders such as SNCC, the Black Panther Party, or Stokely Carmichael.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks as follows:

Up to 2 marks for describing changes in strategy or ideology after 1965 (e.g., rejection of interracial cooperation, emphasis on local autonomy, support for armed self-defence).

Up to 2 marks for referring to specific organisations or leaders (e.g., SNCC’s shift toward separatism, the Panthers’ community programmes, Carmichael’s advocacy of Black Power).

Up to 2 marks for evaluating how these debates reshaped the movement, such as creating ideological diversity, altering public perceptions, or prompting federal repression.

High-scoring answers will use specific evidence and show a clear understanding of how internal debates transformed the movement.