AP Syllabus focus:

‘Activists targeted barriers to voting and political participation, pressuring federal officials to protect civil rights and expand democratic access.’

The Landscape of Disfranchisement in the Early 1960s

African Americans across the South faced entrenched obstacles that severely restricted their access to the ballot box. Although constitutional amendments had theoretically guaranteed voting rights, state and local officials manipulated electoral systems to exclude Black citizens. These discriminatory practices ensured that political power remained concentrated in white hands, weakening African Americans’ capacity to influence policy, hold officials accountable, or secure equal protection under the law.

Structural Barriers to Voting

Segregationist authorities deployed a range of techniques designed to deny African Americans political agency while maintaining the veneer of legal legitimacy. These included:

Literacy tests requiring applicants to interpret complex constitutional clauses

Poll taxes that imposed economic burdens on low-income Black communities

Intimidation and violence, often carried out by local law enforcement or vigilante groups

Arbitrary registration procedures, including limited office hours and frequent purges of voter rolls

Poll Tax: A fee required to vote in many Southern states, disproportionately affecting African Americans and poor citizens and serving as a key tool of disfranchisement.

Although some barriers were challenged through litigation, activists increasingly recognised that direct action and federal legislation were necessary to secure durable voting rights.

Grassroots Campaigns for Voting Rights

Local organising formed the foundation of voting rights activism. Community leaders, church networks, and youth organisers mobilised residents to attempt registration, document discrimination, and challenge the legitimacy of exclusionary systems. These campaigns exposed how state-level obstruction undermined democratic participation.

SNCC, SCLC, and Local Leadership

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) played a crucial role in building long-term organising efforts in rural areas where poverty and intimidation were most acute. SNCC workers lived among local residents, developing trust and strengthening political consciousness. In contrast, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) often launched high-profile campaigns designed to attract national attention and pressure policymakers.

Despite differences in strategy, both organisations aimed to create conditions in which federal intervention became unavoidable. Their efforts demonstrated that disfranchisement was not the result of apathy but of deliberate political structures.

Selma and the National Crisis of Voting Rights

One of the most pivotal moments in the movement occurred in Selma, Alabama, where African American registration rates remained extremely low despite repeated attempts to challenge discriminatory practices. Activists launched sustained protests in 1965, culminating in the violent events of “Bloody Sunday,” when state troopers attacked peaceful marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

This photograph shows the Selma to Montgomery march of 1965, illustrating the scale and determination of the campaign that followed the violence of Bloody Sunday. It highlights the collective mobilisation that compelled federal authorities to act. The image includes full march scenes that extend beyond the specific moment described but remains directly relevant to the Selma campaign. Source.

The Impact of Bloody Sunday

Televised images of the violence galvanised national outrage and intensified demands for federal action. Selma revealed the stark divide between constitutional guarantees and local realities. The crisis created an atmosphere in which federal officials, including President Lyndon B. Johnson, could no longer justify incremental approaches.

The brutality in Selma thus became a critical turning point, linking grassroots activism with legislative momentum.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 as a Response to Activist Pressure

Federal action came in the form of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, which directly confronted state-level suppression.

This image captures the moment President Johnson handed a signing pen to John Lewis after signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It visually represents the federal government’s decisive response to the grassroots campaigns described in the notes. Additional individuals appear in the background, offering broader historical context beyond the immediate legislative act. Source.

The Act sought not only to prohibit discriminatory practices but also to prevent future attempts to evade federal protections.

Key Features of the Voting Rights Act

Several core provisions reshaped the political landscape:

Section 2, banning voting discrimination nationwide

Section 5, imposing preclearance requirements on jurisdictions with histories of discrimination

Section 4(b), establishing the formula for determining which areas required federal oversight

Deployment of federal examiners and registrars to ensure fair registration

Preclearance: A requirement mandating that certain states and localities obtain federal approval before implementing changes to voting procedures, preventing discriminatory laws from taking effect.

The VRA created a proactive enforcement model, allowing the federal government to intervene before discriminatory policies could be implemented.

Transforming Political Power Through Enfranchisement

The expansion of voting rights triggered major shifts in political representation and policymaking across the South. African Americans gained access not only to the ballot but also to the mechanisms of democratic participation that had been systematically denied for decades.

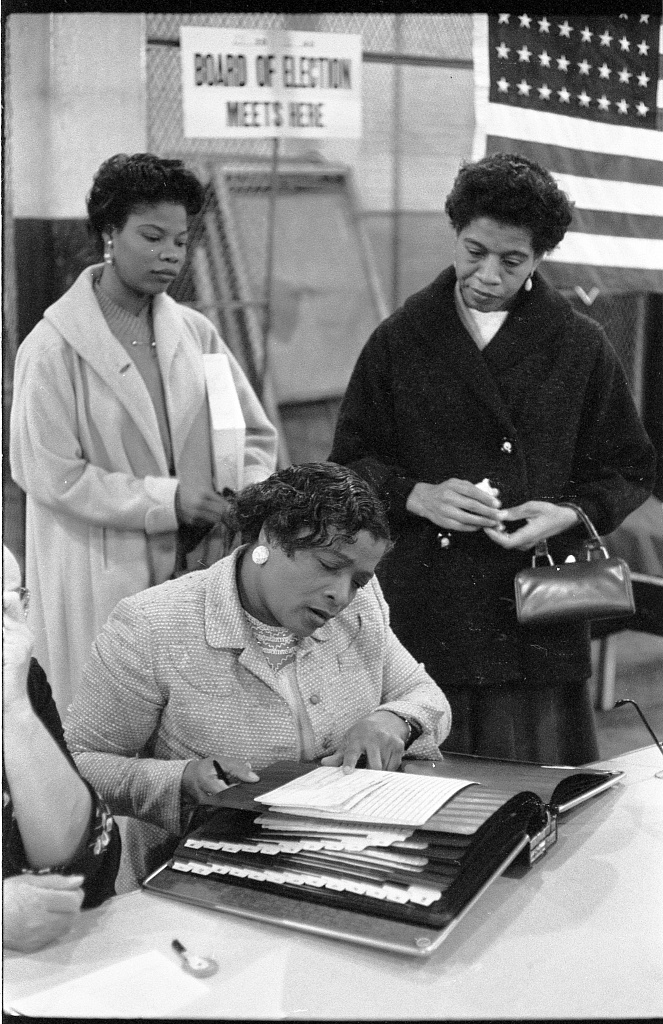

This photograph shows African American women participating in the voting process, illustrating the broader theme of democratic engagement discussed in the notes. Although taken in 1957 in a northern setting, it provides a clear visual example of Black citizens interacting with electoral institutions. The image includes contextual details not specific to the 1960s South but remains relevant for showing the significance of access to voting mechanisms. Source.

Effects on Local and National Politics

Wider enfranchisement reshaped political dynamics through:

Dramatic increases in African American voter registration

Election of Black officials at local, state, and federal levels

Diminishing strength of segregationist political machines

Greater federal oversight of local elections, ensuring continuing compliance

These developments redistributed political power and created space for new coalitions advocating civil rights, economic equality, and community representation.

Ongoing Challenges to Political Participation

While the VRA represented a monumental step forward, activists continued to face structural inequalities that limited full political participation. Economic disparities, unequal access to education, and local resistance persisted in many regions.

Continuing Activist Strategies

To sustain political gains, civil rights organisations emphasised:

Voter education initiatives

Legal advocacy to defend the VRA in court

Coalition-building to support emerging Black political leaders

Their efforts underscored that voting rights were not static achievements but part of a continuous struggle for democratic equality.

FAQ

Local officials had broad discretion to design and administer literacy tests, allowing them to tailor the difficulty to their desired outcome. White applicants often received simplified questions, while Black applicants faced highly complex or obscure tasks.

This variability ensured that African Americans could be systematically rejected without an explicit breach of state law.

Organisers used networks of churches, sympathetic homeowners, and community groups to provide safe meeting spaces and shelter. They also documented threats and violence to present evidence to national civil rights organisations and the federal government.

Many campaigns relied on carpool systems, night patrols, and coordinated communication to navigate hostile environments.

Employers, landlords, and local authorities often used economic retaliation to discourage registration attempts.

Common tactics included:

Firing employees who tried to register

Evicting tenant farmers or sharecroppers

Cutting off credit from white-owned banks or stores

These pressures forced many to choose between their livelihoods and their political rights.

National audiences were shocked by the televised brutality on Bloody Sunday, especially because marchers were unarmed and visibly peaceful.

The contrast between nonviolent demonstrators and violent law enforcement challenged assumptions about Southern governance and helped build bipartisan support for federal voting rights legislation.

Past court victories had been undermined by local officials who quickly adopted new, equally discriminatory methods once old ones were banned.

Federal supervision ensured:

Immediate intervention when discriminatory practices emerged

Protection of newly registered voters

Standardisation of fair registration procedures

This oversight was designed to prevent cyclical patterns of suppression from resurfacing.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one method used by local officials in the early 1960s to block African Americans from voting, and briefly explain how this method restricted political participation.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a correct method of disfranchisement (e.g., literacy tests, poll taxes, intimidation, arbitrary registration rules).

1 mark for explaining how the method prevented African Americans from registering or voting.

1 mark for linking the method to broader political exclusion or the maintenance of white political dominance.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how grassroots activism and federal legislation between 1960 and 1965 worked together to expand African American political power. In your answer, refer to specific campaigns or events such as Selma and to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks as follows:

Up to 2 marks for describing specific grassroots efforts (e.g., SNCC organising in rural communities, SCLC’s Selma campaign, documentation of discrimination).

Up to 2 marks for explaining how these efforts exposed systemic barriers and increased national pressure for federal action.

Up to 2 marks for analysing how the Voting Rights Act of 1965 expanded political power (e.g., increased voter registration, federal oversight, weakening of segregationist control).

Higher-mark answers will show clear links between activism, federal intervention, and the transformation of political representation.