AP Syllabus focus:

‘As Vietnam escalated, youth-led protest expanded, questioning U.S. policy and increasing conflict over dissent and patriotism.’

Escalating U.S. involvement in Vietnam ignited widespread campus activism, as students challenged government policy, expanded antiwar protest networks, and heightened national conflicts over dissent, patriotism, authority, and democratic participation.

The Expansion of Youth-Led Protest

Student activism surged as Vietnam intensified, particularly after major troop deployments in 1965. Many young Americans questioned whether the war aligned with democratic values and constitutional principles. The rise of mass higher education—with millions attending colleges for the first time—created environments conducive to political engagement, debate, and mobilization.

Key Drivers of Campus Engagement

Students reacted to a combination of political, moral, and personal pressures that made the war feel immediate and consequential.

• Draft policies converted abstract foreign policy into a personal fate for young men, intensifying scrutiny of government decisions.

• University communities fostered networks that enabled rapid organization, publication, and protest.

• Expanding media coverage exposed students to wartime brutality and contradictory official statements, fueling doubts about credibility.

• The growth of postwar youth culture encouraged broader questioning of authority and tradition.

Selective Service System arose as a frequently targeted institution, especially because local draft boards held broad discretionary power.

Selective Service System: Federal agency responsible for administering the military draft, determining eligibility, and issuing classifications for potential conscripts.

Student challenges to draft procedures contributed to wider critiques of executive power and Cold War priorities, linking campus activism to national debates.

Student Organizations and Mobilization

Prominent groups shaped the direction and intensity of antiwar protest. The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) expanded rapidly, positioning campus dissent as part of a broader democratic revitalization. SDS chapters held teach-ins, published critiques of containment, and challenged assumptions about the Cold War.

The Teach-In Movement

Teach-ins emerged as a distinctive form of academic protest beginning in 1965.

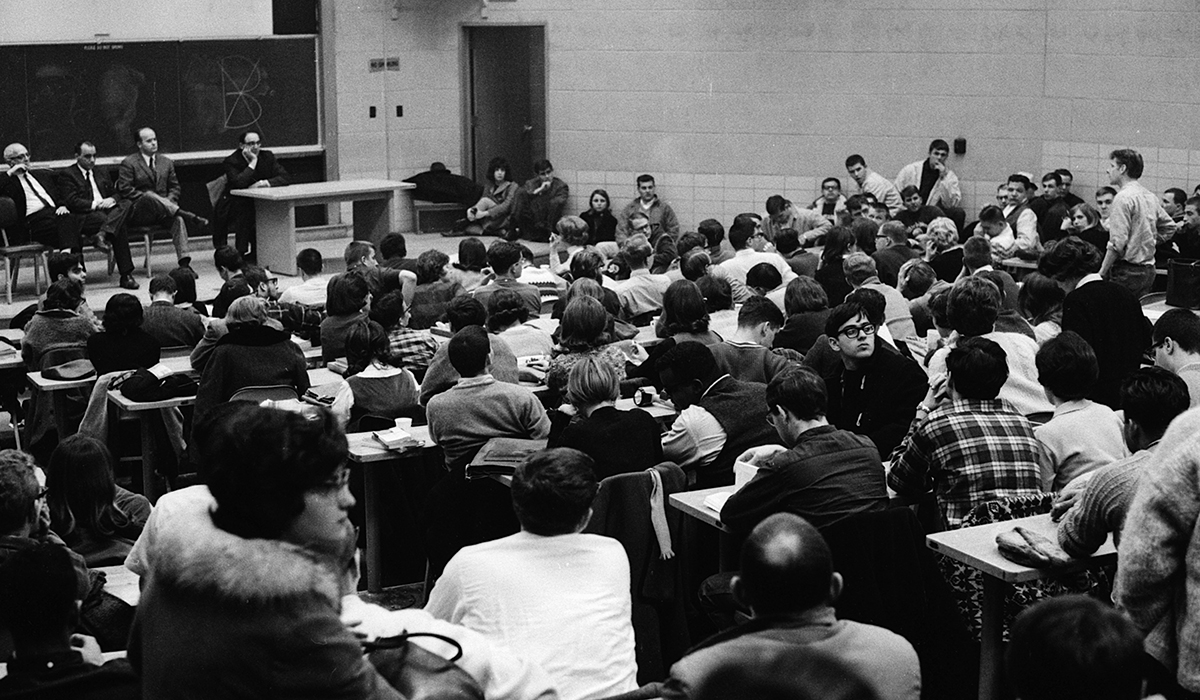

Students and faculty gather in a packed lecture hall during one of the earliest Vietnam War teach-ins in March 1965. The scene illustrates how teach-ins transformed classrooms into extended forums on foreign policy and constitutional debate. The image includes specific institutional detail beyond the syllabus but clearly models the type of campus forum described in the notes. Source.

• Professors and students met for extended sessions to debate war strategy, moral implications, and constitutional questions.

• Unlike rallies, teach-ins emphasized open inquiry, attracting thousands and legitimizing dissent within intellectual life.

• Media coverage of early events at the University of Michigan and the University of California, Berkeley amplified their national impact.

The teach-in became one of the first mass forms of antiwar communication, bridging activism and scholarship and challenging norms of political neutrality on campus.

Escalation of Protest Tactics

As U.S. involvement deepened, student actions became more confrontational. Demonstrators increasingly framed the war as a violation of democratic ideals and human rights. This escalation reflected frustration with government intransigence and distrust of official narratives following developments such as the Tet Offensive in 1968.

Forms of Direct Action

Students adopted a wide range of protest tactics that highlighted moral urgency and broadened participation.

Dickinson College students gather outdoors in 1969 to protest the Vietnam War, many signaling support or solidarity through raised hands and peace signs. The scene captures the nonviolent mass participation typical of campus movements. The image contains institution-specific context not required by the syllabus but closely reflects the forms of demonstration described in the notes. Source.

• Sit-ins at draft boards and university buildings aimed to obstruct military recruitment and expose institutional complicity.

• Marches and mass rallies on campuses created visible solidarity networks and attracted national attention.

• Draft card burnings, protected at first as symbolic speech but later criminalized, publicly rejected wartime authority.

• Building occupations, such as those at Columbia University in 1968, protested not only the war but also university governance and research ties to the defense establishment.

These actions reflected a shift from debate to direct confrontation, intensifying national polarization over dissent and patriotism.

Government and Institutional Responses

Federal and state authorities viewed campus protest as both a political and security issue. As demonstrations expanded, officials questioned whether dissent undermined national unity during wartime. Political leaders charged activists with lacking patriotism or aiding communist interests, echoing lingering anxieties from earlier Cold War fears.

Surveillance and Policing

Government agencies monitored student groups and sought to limit disruptive protest.

• The FBI’s COINTELPRO targeted antiwar organizations through infiltration, surveillance, and attempts to sow internal divisions.

• Local police increasingly intervened on campuses, sometimes at university request, leading to clashes that deepened mistrust.

• Public universities faced political pressure to discipline activists or restrict protests, provoking debates about First Amendment protections.

Campus administrators struggled to balance maintaining order with protecting academic freedom, revealing tension between institutional authority and student rights.

The Kent State and Jackson State Shootings

By 1970, growing frustration, unrest, and government force culminated in deadly confrontations that shifted national opinion. The U.S. decision to expand the war into Cambodia sparked widespread campus strikes. At Kent State University, National Guardsmen opened fire on protesters, killing four students.

Student photojournalist John Filo observes National Guardsmen and assembled students on May 4, 1970, capturing the tense environment leading up to the Kent State shootings. The image reflects the militarized presence and heightened confrontation on campuses during the later stages of the war. It includes contextual detail about the photographer and vantage point beyond syllabus requirements, enriching understanding of the moment’s atmosphere. Source.

Days later, police at Jackson State College killed two more during demonstrations by predominantly Black students.

These tragedies intensified national divisions over dissent and reinforced concerns about the government’s willingness to use violence against its own citizens.

Media, Public Opinion, and the Question of Patriotism

Television coverage of campus protest made student activism a central battleground for public opinion. Supporters argued that dissent represented democratic engagement and moral responsibility. Critics condemned activists as unpatriotic or irresponsible, contributing to generational and ideological polarization.

Growing Conflict over National Identity

Debates about the war increasingly became debates about the meaning of citizenship.

• Activists claimed that speaking against injustice was a patriotic duty.

• Opponents insisted that wartime loyalty required unity and deference to elected leaders.

• Many Americans struggled to reconcile protest with traditional expectations of national solidarity.

This conflict shaped broader political realignments in the 1970s, as concerns about order and dissent influenced emerging “law and order” politics.

Legacy of Campus Antiwar Activism

Youth-led protest became a defining feature of the Vietnam era, influencing public debate, shaping the war’s political trajectory, and expanding expectations for civic participation. University activism forged new models of democratic engagement and left a lasting imprint on American political culture.

FAQ

Administrations often attempted to balance institutional stability with the protection of academic freedom, producing varied responses that influenced protest dynamics.

Some universities tolerated teach-ins and peaceful demonstrations, which allowed activism to grow and normalised political engagement. Others imposed restrictions on assembly, disciplined student leaders, or invited police onto campus, escalating confrontations.

Administrative decisions about defence-related research contracts also heightened tensions, as students criticised universities for supporting the war effort.

University students often received temporary deferments, which created a perception of privilege and moral tension within the antiwar movement.

Many activists argued that deferments unfairly shielded middle-class and white students while leaving working-class and minority youths more vulnerable to conscription.

This perceived inequality led some students to reject deferments voluntarily, organise draft resistance counselling, or protest university cooperation with Selective Service officials.

Faculty involvement gave protests intellectual legitimacy and organisational support.

Lecturers participated in or helped organise teach-ins, offering historical, legal and ethical critiques of the war that strengthened student arguments.

Some faculty senates passed resolutions opposing the war or condemning the presence of law enforcement on campus, while a minority faced criticism for supporting more radical tactics or refusing to cooperate with university directives.

Variation reflected local political cultures, institutional structures and the presence of military infrastructure.

• Large public universities with Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) programmes often experienced more direct action, such as building occupations or blockades.

• Liberal arts colleges tended to host smaller-scale demonstrations, discussion forums and symbolic protests.

• Campuses in conservative regions sometimes faced stronger community backlash, increasing tensions between students and local authorities.

Antiwar activism reshaped daily life, prompting debates within classrooms, student unions and residence halls.

Some students became deeply involved in organising, altering social circles and redefining campus identities around political engagement. Others felt alienated or pressured, viewing activism as disruptive or polarising.

Universities also saw shifts in curriculum, with increased interest in political science, international affairs and contemporary history courses responding to student demand for deeper contextual understanding.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one reason why university campuses became major centres of anti–Vietnam War protest during the 1960s. Explain how this reason contributed to the growth of student activism.

Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason, such as the draft, expansion of higher education, or exposure to media coverage.

• 1 mark for explaining how the reason intensified student concerns (e.g., draft made the war personally consequential; media revealed contradictions in official statements).

• 1 mark for linking the reason to increased mobilisation on campuses (e.g., students formed organisations, held teach–ins, or staged demonstrations).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain the factors that contributed to the escalation of antiwar protest tactics on university campuses between 1965 and 1970. To what extent did government and institutional responses shape the development of student activism?

Question 2

• 1–2 marks for identifying relevant factors such as frustration with government escalation of the war, distrust after events like the Tet Offensive, and rising youth willingness to challenge authority.

• 1–2 marks for describing specific protest tactics (e.g., sit–ins, draft card burnings, building occupations) and explaining why they became more confrontational.

• 1 mark for explaining government and institutional responses such as surveillance (e.g., FBI involvement), police intervention, or administrative restrictions.

• 1 mark for assessing the extent to which these responses intensified activism (e.g., clashes heightened resentment, strengthened protest networks, or framed dissent as a constitutional issue).