AP Syllabus focus:

‘Civil rights advocates used legal challenges to end segregation, including landmark Supreme Court decisions that questioned “separate but equal.”’

Legal battles after World War II challenged entrenched racial segregation, as civil rights lawyers strategically targeted discriminatory laws, culminating in Brown v. Board of Education, which transformed American constitutional principles and social institutions.

The Legal Foundations of Early Civil Rights Victories

Civil rights advocates in the 1940s and 1950s pursued a deliberate legal campaign to undermine Jim Crow segregation, especially in public education. These efforts were led primarily by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) under the guidance of Thurgood Marshall, who believed that dismantling segregation required demonstrating its inherent inequality within constitutional frameworks.

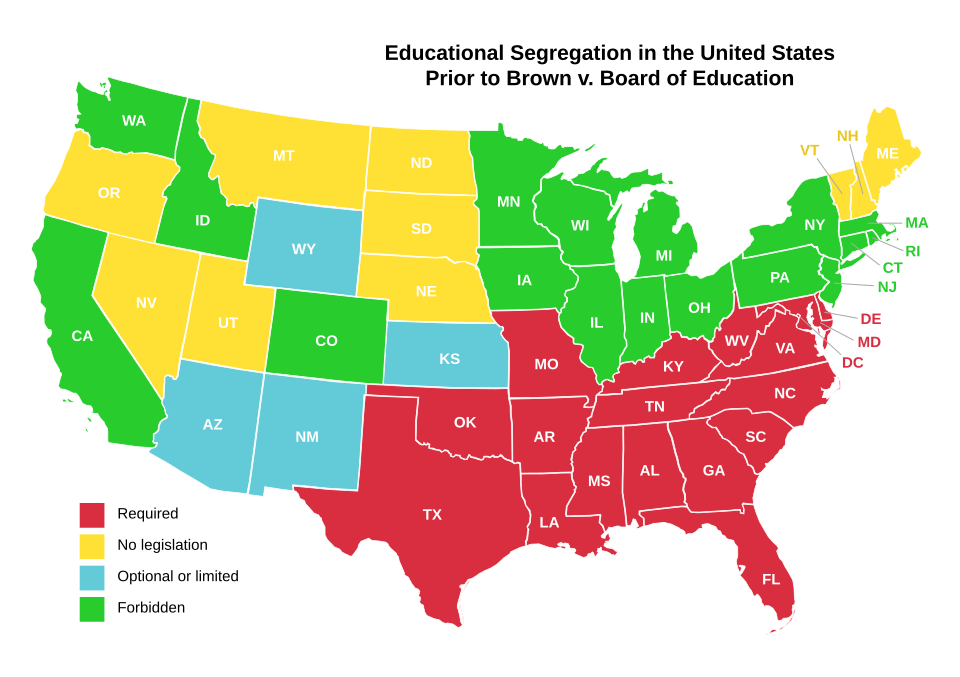

Prior to Brown, school segregation varied by region, with some states mandating separate schools by law and others allowing or banning segregation.

Map of the United States showing school segregation laws before Brown v. Board of Education. States are color-coded to reflect where segregation was required, permitted, banned, or not addressed. Although the map contains more detail than students must memorize, it clearly illustrates the legal landscape NAACP lawyers confronted. Source.

The Role of the NAACP and Legal Strategy

The NAACP’s multi-step approach focused on challenging the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Lawyers sought to show that segregated institutions were unequal in practice and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Equal Protection Clause: A constitutional principle in the Fourteenth Amendment requiring states to apply the law equally and prohibiting discrimination under state authority.

To build momentum, the NAACP pursued incremental victories, typically attacking segregation in graduate and professional education before confronting racial separation in elementary and secondary schools. This strategy aimed to create binding precedents and expose the unsustainability of maintaining “equal” conditions across racially segregated systems.

After securing early successes, the organization increasingly shifted toward direct challenges to segregation itself, arguing that separation created psychological harm and civic inequality.

Key Precedents Before Brown

Before the 1954 decision, several significant cases weakened the legal validity of segregation:

Sweatt v. Painter (1950) – The Court ruled that a separate Black law school in Texas could never match the intangible qualities of the white institution, including reputation and professional networks.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950) – The Court found that segregating a Black graduate student within the same institution violated his ability to learn, collaborate, and participate fully.

These decisions collectively undermined claims that segregated education could ever be truly equal, preparing the legal foundation for a broader challenge to Plessy.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): The Landmark Decision

The Brown v. Board of Education case consolidated multiple lawsuits from Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware, all challenging segregated public schools. The plaintiffs argued that segregation stigmatized African American children and denied them equal educational opportunities.

One of the five consolidated cases involved Linda Brown, a Black third-grader in Topeka, Kansas, whose family challenged the denial of access to a nearby white school.

Front view of Monroe Elementary School, the former Black school central to Brown v. Board of Education. The building represents the real educational inequality at issue in the case. The National Park Service signage visible in the image goes beyond syllabus requirements but highlights modern preservation of this historic site. Source.

The Court’s Reasoning

Chief Justice Earl Warren, seeking unanimity, framed segregation as incompatible with democratic ideals and modern understandings of child development. He rejected the historical reasoning behind Plessy, stating that the doctrine had no place in public education.

Segregation: A system of enforced separation of racial groups in public or private facilities, typically justified through discriminatory law or custom.

Drawing on social science evidence, including studies by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, the Court argued that segregation produced feelings of inferiority among Black students, impairing their motivation to learn and violating the Equal Protection Clause.

The Decision’s Core Holding

In May 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” This statement directly overturned Plessy in the realm of public education and signaled a profound constitutional shift.

The Court ruled that public school segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment and denied African American children equal protection under the law. This decision provided a powerful judicial endorsement for integration and set a national precedent.

Brown II (1955) and Implementation Challenges

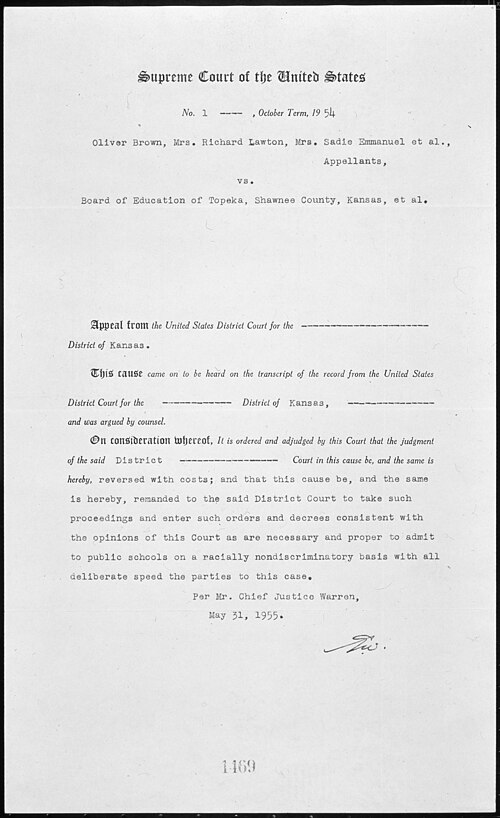

Because the 1954 ruling did not establish specific enforcement procedures, the Court revisited the issue in Brown II (1955). The justices required that school districts desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

In 1955, in Brown II, the Court issued an implementation ruling instructing local authorities to desegregate public schools “with all deliberate speed,” leaving room for delay and resistance.

Scan of the Supreme Court’s judgment implementing Brown v. Board of Education. The document contains the directive for desegregation to proceed “with all deliberate speed,” a phrase that shaped local resistance. While the full legal text exceeds syllabus detail, students should focus on its role in guiding and complicating enforcement. Source.

Ambiguities and Resistance

The phrase lacked clear timelines and allowed segregationists to delay compliance. Many Southern states adopted tactics to preserve segregation, such as:

Massive Resistance policies, including school closures and funding cuts for integrated districts

Legal maneuvers designed to slow or circumvent integration orders

Public campaigns promoting segregation as a defense of “states’ rights”

These responses reflected the contentious political climate surrounding federal authority and highlighted the gap between judicial rulings and practical implementation.

Broader Impact of Legal Victories

Although Brown faced resistance, the ruling profoundly shaped the trajectory of the Civil Rights Movement.

Transforming Constitutional Principles

The decision reaffirmed federal responsibility to enforce civil rights, even against entrenched state opposition. It also advanced a broader interpretation of equality, suggesting that laws reinforcing racial hierarchy were inherently unconstitutional.

Mobilizing Social and Political Activism

Legal victories encouraged a new wave of direct-action protest and energized organizations committed to dismantling segregation. Communities drew inspiration from the Court’s declaration, perceiving it as a moral and legal affirmation of their demands for justice.

Expanding Federal Engagement

Following Brown, federal courts increasingly supervised local school boards, and the executive branch—particularly under Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy—became more involved in enforcing integration orders. These developments deepened debates over the proper relationship between federal and state power.

Long-Term Significance

The legal victories culminating in Brown v. Board of Education reshaped national discourse about race, citizenship, and the Constitution. By declaring segregation incompatible with equality, the Supreme Court established a foundational precedent that would support subsequent civil rights legislation and future legal challenges to discrimination across American society.

FAQ

The NAACP targeted locations where segregated school systems were clearly unequal and where families were willing to withstand social and economic pressure. It prioritised cases that could generate strong constitutional arguments and involved plaintiffs who were stable community members seen as credible in court.

The organisation also selected districts where judges were more likely to issue favourable rulings, creating strategic precedents for future challenges.

Social scientists, including Kenneth and Mamie Clark, provided evidence on the psychological effects of segregation on Black children. Their “doll tests” suggested that segregation fostered low self-esteem and internalised racism.

Although not the sole factor, such research helped the Court argue that segregation inflicted intangible harms beyond material inequality, strengthening the rejection of “separate but equal.”

Chief Justice Earl Warren believed a divided decision would undermine the ruling’s moral authority and encourage resistance.

To secure unanimity, he avoided inflammatory language, focused on broad constitutional principles, and crafted a short, accessible opinion that all justices could support despite differing legal philosophies.

Many Southern leaders invoked “states’ rights,” claiming education was a state matter outside federal intervention. They framed resistance as defence of local autonomy rather than explicit defence of segregation.

States also used legal technicalities, new statutes, and administrative barriers to slow integration while publicly asserting commitment to law and order.

Local resistance often took less visible but highly effective forms, including:

Pressuring Black families who attempted to enrol in white schools

Reassigning teachers to maintain segregation informally

Creating private “segregation academies” to replace integrated public schools

These grassroots efforts operated alongside state-level policies, slowing practical implementation despite federal legal victories.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education challenged the legal doctrine of “separate but equal.”

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying that Brown v. Board declared segregated schools inherently unequal.

1 mark for explaining that this ruling overturned the precedent established in Plessy v. Ferguson.

1 mark for noting that the decision found segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the significance of legal strategies used by the NAACP in achieving the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for identifying the NAACP’s long-term legal campaign against segregation.

1 mark for describing the use of incremental cases (e.g., Sweatt v. Painter, McLaurin v. Oklahoma) to undermine “separate but equal.”

1 mark for explaining how these cases demonstrated the inherent inequality of segregated education.

1 mark for linking NAACP strategies to evidence used in Brown, such as psychological research showing harm to Black children.

1 mark for analysing how these strategies helped persuade the Supreme Court to issue a unanimous ruling.

1 mark for evaluating the broader significance of this approach, such as its role in shifting civil rights activism and constitutional interpretation.