AP Syllabus focus:

‘Grassroots direct action and nonviolent protest tactics expanded the movement, demonstrating the power of organized community resistance.’

Nonviolent mass protest in the 1950s marked a transformative phase in the civil rights movement, as grassroots activism reshaped tactics, mobilized communities, and challenged entrenched systems of segregation nationwide.

The Rise of Nonviolent Mass Protest

Grassroots activism in the 1950s emerged as a powerful response to entrenched segregation, racial violence, and unequal access to political and economic rights. Drawing upon longstanding traditions of African American community organizing, local leaders and ordinary citizens developed new strategies of nonviolent direct action, emphasizing disciplined protest over confrontation. These methods built momentum for later national civil rights victories and demonstrated that collective resistance could pressure institutions resistant to change.

Intellectual and Strategic Foundations

The nonviolent movement drew heavily from Christian ethics, Black church organizing traditions, and the writings of Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of satyagraha influenced key civil rights leaders. Activists argued that moral force and public pressure could expose the injustice of segregation more effectively than violent resistance. Nonviolence also offered a strategic advantage: by refusing to retaliate, protesters undermined segregationists’ claims that African American activism posed a threat to social order.

Nonviolent Direct Action: A coordinated strategy of peaceful protest designed to confront injustice, create tension, and force negotiation without the use of physical violence.

Nonviolent direct action became a foundational approach in the 1950s, shaping how activists organized boycotts, demonstrations, and community coalitions to challenge discriminatory systems.

The Central Role of Black Churches and Local Organizations

Local institutions—especially Black churches—served as key hubs for mobilization. Led by charismatic preachers and respected community organizers, churches provided gathering spaces, communication networks, and moral justification for protest.

Functions of Black Churches in Movement Building

Communication centers: Churches spread information quickly across communities unfamiliar with national organizations.

Training grounds: They hosted workshops on protest discipline, including how to remain nonviolent under provocation.

Logistical foundations: Congregations raised funds, organized transportation, and provided mutual aid during campaigns.

Leadership incubators: Ministers such as Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as influential movement voices through church networks.

These institutions offered not only structure but legitimacy, linking religious identity to political activism and strengthening solidarity among participants.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott as a Turning Point

The 1955–56 Montgomery Bus Boycott demonstrated the power of sustained grassroots protest. Sparked by Rosa Parks’ refusal to surrender her seat to a white passenger, the boycott mobilized thousands of African Americans to avoid city buses for over a year.

Key Elements of the Boycott

Mass participation: Nearly the entire Black population of Montgomery joined the effort.

Alternative transportation: Carpools and organized ride-sharing minimized disruptions to workers’ lives.

Central leadership: The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) coordinated strategy and negotiations.

Legal challenges: Activists pursued court action alongside protest, culminating in the 1956 Supreme Court ruling striking down segregated buses.

The boycott’s success proved that coordinated, nonviolent community action could win major victories, inspiring similar activism across the South.

Sit-Ins and the Spread of Direct Action Tactics

By the late 1950s, students became increasingly influential in shaping nonviolent protest. Sit-ins began when African American college students challenged segregated lunch counters by refusing to leave after being denied service.

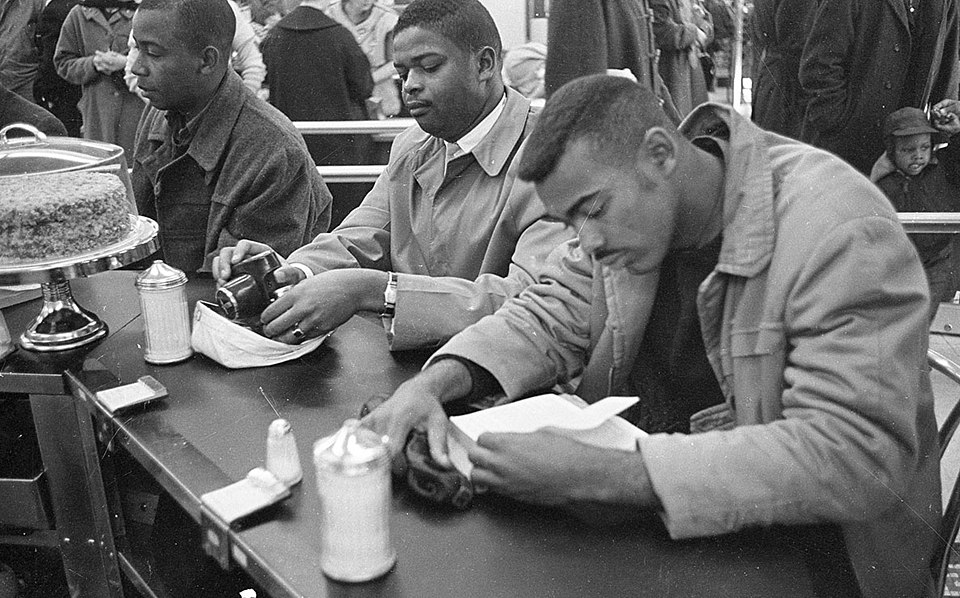

This photograph depicts three African American protesters at a Durham Woolworth’s sit-in in February 1960, illustrating the disciplined nonviolent tactics of student activists. Their calm refusal to leave exemplifies direct challenges to segregated public spaces. The specific Durham location exceeds syllabus requirements but provides a representative visual of sit-in methods. Source.

Characteristics of Sit-In Tactics

Disciplined nonviolence: Participants trained to endure harassment without retaliation.

Disruption of daily business: Denying service to protesters forced storeowners to confront discriminatory practices.

Media visibility: Images of calm students facing hostile crowds generated widespread sympathy.

Rapid diffusion: Sit-ins spread to dozens of cities through student networks and growing youth involvement.

These demonstrations expanded the geography of nonviolent protest and demonstrated the increasing role of young people in the struggle for racial equality.

This image shows the preserved Greensboro Woolworth’s lunch counter where students initiated a landmark sit-in in 1960, now displayed at the National Museum of American History. The stools and counter provide a tangible representation of nonviolent protest sites. Exhibit details extend beyond syllabus needs but effectively illustrate the tactic’s historical significance. Source.

The Emergence of Coordinated Regional Movements

Although early activism was often localized, regional leadership soon emerged to unify campaigns. Organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) provided strategic guidance, training, and cross-community coordination.

SCLC’s Influence

Promoted nonviolent direct action as the core tactic of the civil rights movement

Coordinated protests across Southern states

Offered leadership workshops and theological justification for protest

Encouraged grassroots participation rather than top-down directives

SCLC helped transform scattered protests into a broader movement with shared principles, enhancing the national profile of nonviolent resistance.

Nonviolence, Media, and Public Opinion

Media coverage played a crucial role in shaping public response to nonviolent protest. Images of peaceful demonstrators facing police violence, mob intimidation, or mass arrests exposed the brutality of segregation to national audiences.

Effects of Media Visibility

Increased pressure on elected officials to address civil rights abuses

Helped shift moderate Northern opinion toward supporting reform

Created moral contrast between activists and segregationists

Elevated civil rights issues into national political debate

Nonviolent protest strategically leveraged this visibility, demonstrating that moral clarity could be a powerful political tool.

Challenges and Internal Debates

Despite the effectiveness of nonviolent protest, activists faced significant challenges. Many African Americans questioned whether nonviolence was sufficient against deeply entrenched racial oppression. Others feared economic retaliation, police brutality, or community division.

Persistent Tensions

Concerns about safety and the emotional burden of nonviolence

Debates over the role of legal challenges versus direct action

Divergent strategies between older clergy-led groups and younger student leaders

Ongoing fear of backlash from white supremacist organizations

Still, the movement’s commitment to nonviolent tactics remained central in the 1950s, forming the strategic foundation for the transformative civil rights campaigns of the 1960s.

FAQ

Activists often underwent workshops that simulated verbal harassment and physical intimidation, helping them practise maintaining composure under pressure.

Training emphasised body posture, eye contact, and silence as tools for de-escalation.

It also taught protesters how to protect themselves without retaliating, such as linking arms or using sit-down formations to avoid being separated or isolated.

These skills ensured that demonstrations remained peaceful even when opponents attempted to provoke violence.

Women frequently managed essential organisational tasks, including arranging transportation networks, coordinating communication chains, and preparing mass meetings.

Many also served as strategists within community groups and church committees, shaping protest logistics and ensuring participation across neighbourhoods.

Their behind-the-scenes labour sustained long-term campaigns like the Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped translate local grievances into structured mass action.

Nonviolent protests often targeted businesses dependent on consistent local spending, meaning even small-scale boycotts could significantly reduce revenue.

Sit-ins disrupted lunch counter operations at busy commercial sites, pressuring managers to negotiate to restore normal business activity.

Because many white-owned establishments relied on Black customers for economic survival, the sustained withdrawal of custom created leverage that neither legal action nor political appeals could immediately generate.

Students brought fresh organisational energy, strong peer networks, and a willingness to confront segregation more directly.

Their campuses served as bases for rapid mobilisation, allowing demonstrations to spread quickly across states.

Students also reframed nonviolent protest as a moral responsibility of youth, helping inspire a generational shift that expanded the movement’s visibility and urgency.

Segregationists increasingly used legal tools such as trespass and disorderly conduct charges to justify arrests and deter participation.

They also coordinated economic retaliation, including job loss or credit denial, to punish activists.

In some communities, officials issued new regulations limiting public assembly or requiring permits, attempting to restrict where and how nonviolent protests could occur.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why nonviolent direct action became a central strategy of the civil rights movement during the 1950s.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., moral authority, strategic contrast with segregationist violence, effectiveness in mobilising communities).

1 mark for describing how this reason influenced movement tactics.

1 mark for explaining why this made nonviolence particularly effective or appealing in the 1950s.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which grassroots organisation shaped the success of nonviolent mass protest in the 1950s.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for identifying ways grassroots organisation contributed to protest success (e.g., churches as organising centres, student involvement, community-wide participation).

1–2 marks for developing these points with specific examples (e.g., Montgomery Bus Boycott logistics, sit-in coordination).

1–2 marks for a reasoned judgement on the extent of grassroots influence compared with other factors (e.g., national leadership, media coverage, legal strategies).