AQA Specification focus:

‘Students should appreciate that deflationary policies are policies to reduce aggregate demand and do not necessarily result in deflation.’

Introduction

Deflationary policies are government or central bank measures designed to reduce aggregate demand (AD). While they may slow price increases, they do not always produce actual deflation.

Deflationary Policies and Aggregate Demand

Deflationary policies aim to lower spending and demand pressures in the economy, often as a response to inflationary concerns. By targeting the components of aggregate demand (consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports), these policies work to curb excessive demand growth. However, they do not necessarily result in deflation, which refers to a sustained fall in the general price level. Instead, their usual effect is to slow inflation or return it to a target range.

Key Concepts

Deflationary Policies: Policies that reduce aggregate demand, generally through contractionary fiscal or monetary tools, aimed at lowering inflationary pressures in the economy.

Deflation: A sustained fall in the general price level, distinct from disinflation, which is a fall in the rate of inflation.

Types of Deflationary Policies

Monetary Policy Measures

Central banks often use monetary tools to manage demand:

Raising interest rates: Higher rates increase borrowing costs and encourage saving, reducing consumption and investment.

Tightening money supply: Through open market operations (selling bonds) or increasing reserve requirements for banks.

Forward guidance: Signalling tighter policy in the future to influence expectations and spending behaviour today.

Fiscal Policy Measures

Governments may reduce demand directly by adjusting taxation and spending:

Higher direct taxes: Cuts disposable income, lowering household consumption.

Increased indirect taxes (VAT, excise duties): Reduces demand for goods and services by raising prices.

Cuts in government spending: Reduces aggregate demand by lowering public sector contributions to GDP.

Effects on Aggregate Demand

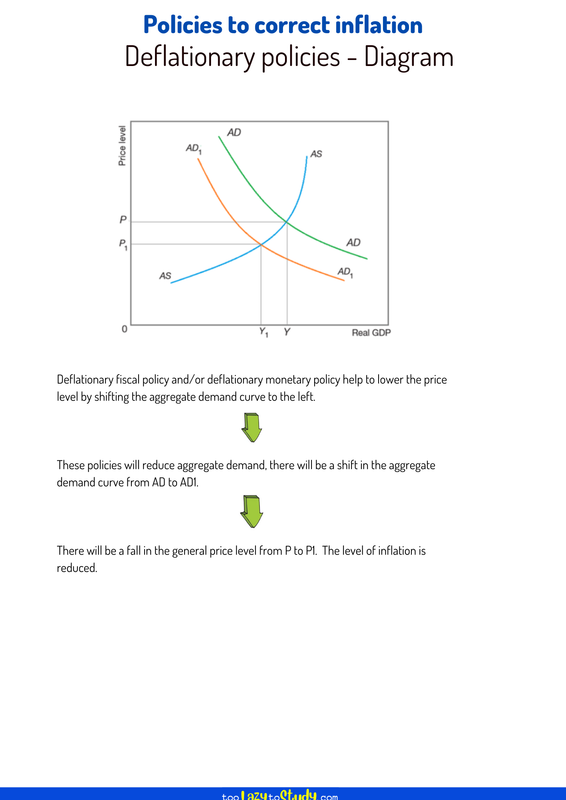

Aggregate demand (AD) represents total planned spending in an economy at different price levels. Deflationary policies shift the AD curve leftward.

Initial position: High AD may create inflationary pressures when output nears full capacity.

Policy effect: Leftward AD shift reduces inflationary pressure, stabilising the economy.

Outcome: Usually results in disinflation (a slowing rate of inflation) rather than outright deflation.

AD/AS Framework

Within the aggregate demand and aggregate supply (AD/AS) model:

A rightward shift of AD risks inflation.

Deflationary policies aim for a controlled leftward shift, aligning output closer to long-run aggregate supply (LRAS).

If excessive, these policies risk creating a negative output gap, leading to higher unemployment.

The diagram illustrates the effect of deflationary policies on the AD curve, showing a leftward shift from AD to AD1, leading to lower output and price levels. Source

Why Deflationary Policies Do Not Always Cause Deflation

Deflation is relatively rare in modern economies because:

Sticky prices and wages: Firms and workers resist lowering prices and wages, even when demand falls.

Expectations of inflation: If people anticipate moderate inflation, firms may still increase prices.

Supply-side factors: Rising costs (e.g., energy prices) may maintain upward pressure on the price level despite weak demand.

Potential Advantages of Deflationary Policies

Inflation control: Reduces the risk of demand-pull inflation spiralling out of control.

Macroeconomic stability: Maintains purchasing power and protects savings.

Policy credibility: Demonstrates government or central bank commitment to price stability, supporting long-term economic confidence.

Potential Disadvantages of Deflationary Policies

Unemployment: Lower demand reduces business revenues, potentially leading to layoffs.

Slower growth: Reduced investment and consumption slow economic expansion.

Worsening inequalities: Tax rises or spending cuts may disproportionately affect lower-income households.

Debt burden: Higher real interest payments if inflation falls, worsening debt positions of firms and households.

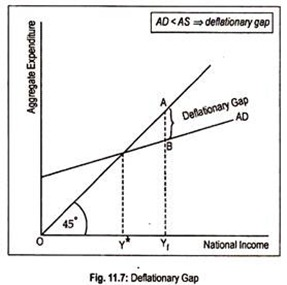

Links to Output Gaps

Output Gap: The difference between actual GDP and potential GDP in an economy. A negative output gap means underused resources; a positive output gap indicates overuse.

Deflationary policies risk creating or widening a negative output gap, with falling demand leading to cyclical unemployment.

The diagram shows a deflationary gap where the aggregate demand curve intersects the 45° line below the full employment level, indicating underutilised resources and potential cyclical unemployment. Source

Evaluation

When considering deflationary policies, economists assess their timing, magnitude, and context:

Timing: Too early an application may choke off recovery.

Magnitude: Overly aggressive policy tightening can destabilise growth.

Context: Policies are more effective against demand-pull inflation than cost-push inflation.

Policymakers often balance deflationary measures with growth objectives, highlighting the importance of coordination between fiscal and monetary policy.

FAQ

Deflationary policies are designed to reduce aggregate demand, often through higher interest rates, higher taxes, or reduced government spending. Their intention is to slow inflationary pressures.

Disinflationary outcomes occur when these policies reduce the rate of inflation, but not necessarily below zero. Deflation, a sustained fall in the price level, is rare and usually not the direct aim of policy.

Deflation can increase the real burden of debt, discourage spending and investment, and risk a deflationary spiral.

Governments and central banks therefore target controlled inflation (often around 2%), using deflationary policies only to bring demand back in line with sustainable growth rather than to push prices downward.

If households and firms expect prices to continue rising moderately, they may keep spending and investing, even when policies attempt to reduce demand.

Conversely, if expectations shift towards falling prices, people may delay consumption and investment, amplifying the contractionary effects of policy and risking a deeper slowdown.

Raising interest rates is a key tool for reducing aggregate demand. Higher rates:

Increase the cost of borrowing for households and firms.

Encourage saving rather than spending.

Strengthen the currency, reducing export demand.

These mechanisms all reduce aggregate demand, but the extent depends on consumer confidence and global economic conditions.

Yes. Policies such as increasing indirect taxes or cutting public spending often disproportionately affect lower-income households, as a larger share of their income goes on essentials.

Wealthier households may be less affected, as they can maintain spending despite tax increases or reduced services. This creates a potential social trade-off when applying deflationary fiscal measures.

Practice Questions

Explain why deflationary policies do not necessarily result in deflation. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that deflationary policies reduce aggregate demand to control inflationary pressures.

1 mark for explaining that this usually results in disinflation (slower rate of inflation), not a sustained fall in the price level.

Using an aggregate demand and aggregate supply (AD/AS) diagram, analyse how deflationary fiscal policies might affect unemployment in an economy operating close to full capacity. (6 marks)

1 mark for correctly identifying a deflationary fiscal policy (e.g., higher taxes, reduced government spending).

1 mark for linking the policy to a leftward shift in aggregate demand.

1 mark for correctly applying the AD/AS model to show a fall in equilibrium output.

1 mark for explaining how reduced output leads to lower demand for labour.

1 mark for linking this outcome to an increase in unemployment.

1 mark for recognising that the impact is greater if the economy is close to full capacity, as demand falls more sharply into a negative output gap.