AQA Specification focus:

‘The model of comparative advantage.’

Introduction

Comparative advantage explains how countries gain from trade by specialising in goods they produce relatively efficiently. It is central to understanding international trade patterns.

Understanding Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage is a key concept in international economics, first formalised by economist David Ricardo. It highlights how even if one country is less efficient at producing all goods compared to another, it can still benefit from trade by specialising in the good it produces at a lower opportunity cost.

Comparative Advantage: When a country can produce a good or service at a lower opportunity cost compared to another country.

This principle differs from absolute advantage, which refers to producing more of a good with the same resources. Comparative advantage shows that mutual gains from trade are possible even when one nation has no absolute advantage.

The Model of Comparative Advantage

The model assumes that each country should specialise in the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage, then engage in international trade. This specialisation leads to a more efficient allocation of global resources, increasing overall production and consumption possibilities.

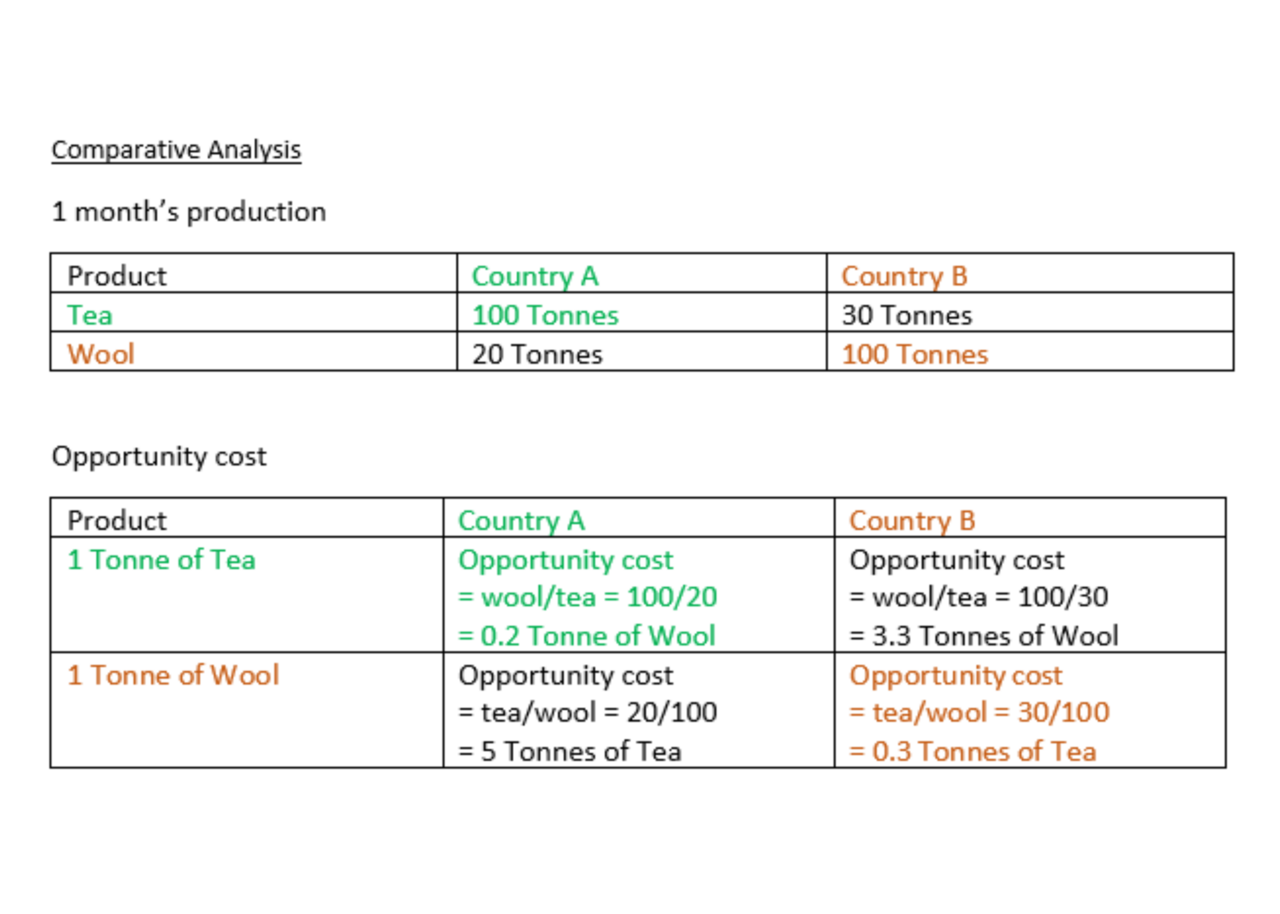

This diagram demonstrates how two countries can increase total output by specialising in the good for which they have a comparative advantage, as opposed to producing both goods independently. Source

Key Assumptions of the Model

Two-country, two-good framework: Simplified structure with only two nations and two products.

Constant opportunity cost: Each additional unit produced involves the same trade-off.

Free trade: No tariffs, quotas, or subsidies that distort trade.

Perfect factor mobility within countries: Labour and capital can move freely between industries domestically.

No transport costs: Goods move without cost between nations.

While these assumptions simplify reality, they clarify the fundamental logic of comparative advantage.

Opportunity Cost and Comparative Advantage

Opportunity cost is the cornerstone of the model. A country has a comparative advantage in the good where the opportunity cost of producing it is lower compared to other goods.

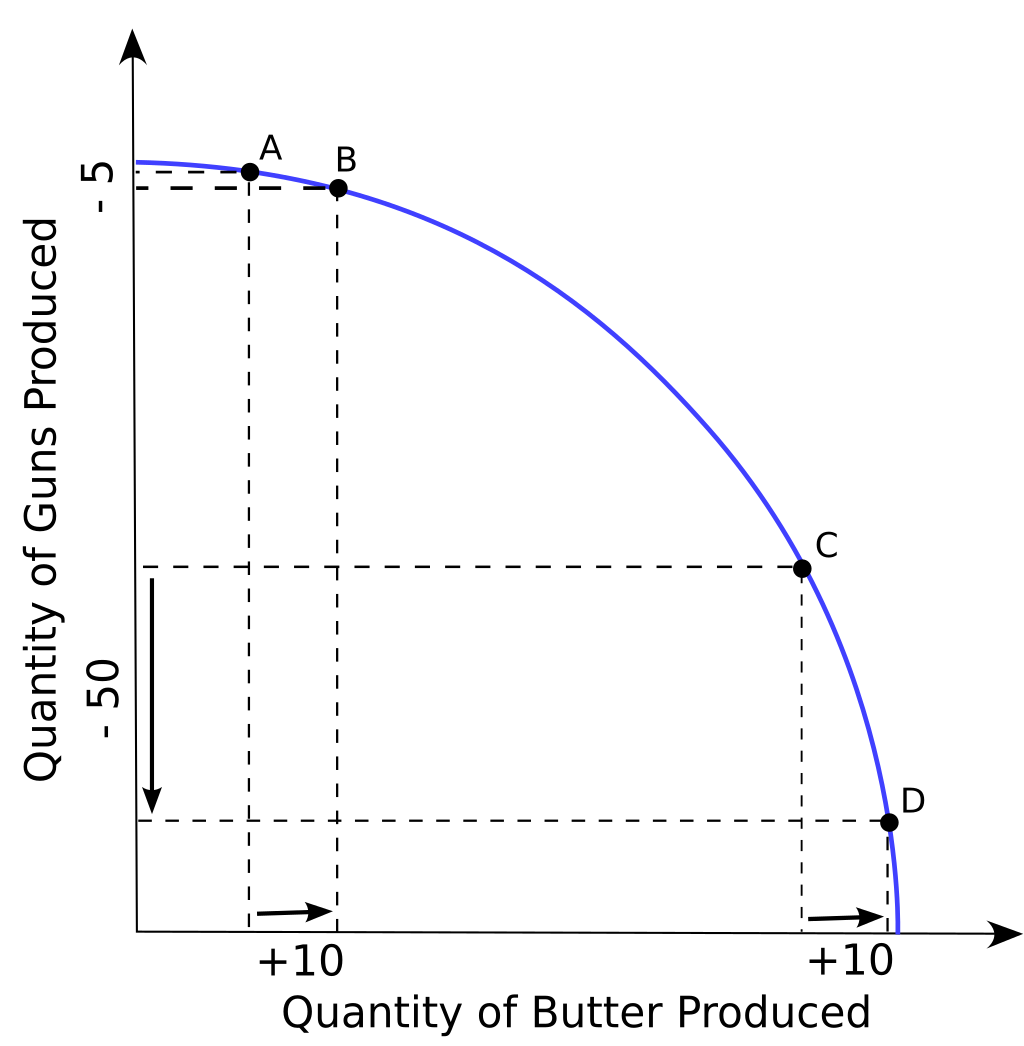

The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) illustrates the maximum possible output combinations of two goods, highlighting the opportunity cost involved in reallocating resources between them. Source

Opportunity Cost: The value of the next best alternative forgone when making an economic decision.

This means countries benefit when they allocate resources towards goods where they sacrifice less production of other items.

Gains from Specialisation and Trade

When countries specialise based on comparative advantage:

Total output increases beyond what either country could achieve alone.

Global efficiency improves because resources are allocated where they are most productive.

Consumption possibilities expand, allowing countries to consume outside their production possibilities frontier (PPF).

Interdependence grows, encouraging international cooperation and integration.

Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF): A curve showing the maximum possible output combinations of two goods given available resources and technology.

Trade allows nations to move beyond their PPF, highlighting the efficiency gains.

Graphical Representation

In diagrams, each country’s PPF shows the maximum goods it can produce. The relative slopes represent opportunity costs. By specialising where opportunity costs are lowest, both nations expand total production. Trade then allows them to share these gains.

Important Features to Note:

Countries benefit even if one is more efficient in producing both goods, as long as their relative opportunity costs differ.

The steeper slope of a PPF indicates a higher opportunity cost of producing that good.

The trade line (terms of trade) reflects the agreed rate of exchange between goods internationally.

Limitations of the Model

Although powerful, the comparative advantage model faces several limitations:

Transport costs can reduce or eliminate trade benefits.

Increasing opportunity costs: Real economies rarely have constant trade-offs.

Non-homogeneous goods: Quality and differentiation matter in real trade.

Imperfect mobility of factors: Labour and capital cannot always move freely within or between nations.

Protectionist policies: Tariffs, quotas, and subsidies often distort trade flows.

Dynamic factors: Technology, productivity, and consumer preferences evolve over time.

These limitations mean comparative advantage serves as a theoretical baseline rather than a perfect prediction of trade outcomes.

Benefits of Comparative Advantage in Practice

Despite limitations, the principle underpins modern trade policies and agreements. Key benefits include:

Higher living standards through access to a wider variety of goods at lower prices.

Encouragement of innovation and efficiency, as firms face international competition.

Economic growth, with trade acting as a stimulus to production and employment.

Resource allocation efficiency, as countries deploy factors of production more productively.

Governments and international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) often reference comparative advantage to justify free trade agreements.

Equations in Comparative Advantage

The concept is often illustrated numerically by calculating opportunity costs.

Opportunity Cost of Good X = Units of Good Y forgone ÷ Units of Good X produced

Good Y forgone = Quantity of alternative good sacrificed

Good X produced = Quantity of chosen good produced

This calculation allows economists to determine which country should specialise in which good.

Conclusion Within the Model

The model of comparative advantage provides a clear theoretical justification for trade. By focusing on opportunity costs and resource allocation, it demonstrates how both developed and developing nations can benefit through specialisation and exchange.

FAQ

David Ricardo formalised the theory of comparative advantage in the early 19th century.

He demonstrated mathematically that trade benefits both nations, even if one is more efficient in producing every good.

Ricardo’s insight shifted focus from absolute efficiency to relative efficiency, highlighting opportunity cost as the key driver of specialisation and trade.

Absolute productivity measures how much a country can produce in total.

Comparative advantage relies on opportunity cost — what must be given up to produce one good instead of another.

A country may be less efficient overall but still face lower opportunity costs in certain goods.

This allows for mutually beneficial trade, regardless of absolute efficiency differences.

Terms of trade refer to the rate at which one good exchanges for another between countries.

If agreed terms fall between each country’s opportunity costs, both benefit.

Too close to one country’s cost may reduce that country’s gains.

A fair balance ensures that both nations see tangible improvements in consumption possibilities.

Key assumptions include:

Constant opportunity costs.

No transport costs.

Perfect factor mobility within a country.

Homogeneous goods.

No protectionism.

In reality, these conditions rarely hold. Nonetheless, the model serves as a useful theoretical foundation to explain why trade often brings efficiency gains.

Comparative advantage is dynamic, not fixed.

It can shift due to:

Technological advances improving productivity.

Changes in resource availability (e.g. discovery of oil).

Investment in education and training.

Evolving consumer preferences.

As these factors develop, a country may lose or gain comparative advantage in certain industries, reshaping trade patterns.

Practice Questions

Define comparative advantage and explain how it differs from absolute advantage. (2 marks)

1 mark for correctly defining comparative advantage (lower opportunity cost in producing a good/service).

1 mark for explaining the difference with absolute advantage (ability to produce more with the same resources).

Using the model of comparative advantage, explain how international specialisation can increase global output. (6 marks)

1 mark for recognising that comparative advantage is based on differences in opportunity cost.

1 mark for stating that countries specialise in goods where they have comparative advantage.

1 mark for explaining that specialisation increases efficiency and allocates resources more productively.

1 mark for noting that total world output increases compared to self-sufficiency.

1 mark for explaining that trade allows countries to consume beyond their production possibilities frontier.

1 mark for recognising assumptions/limitations (e.g. constant opportunity costs, no trade barriers) but still showing how gains from trade arise under the model.