IB Syllabus focus:

‘Addressing climate change requires international cooperation (protocols, treaties, possible cross-border carbon pricing) led by UNFCCC/IPCC and COP processes to stabilize GHGs.’

Global climate change cannot be solved by individual nations alone; it requires collective action, coordination, and governance. International cooperation provides the framework through which agreements, treaties, and institutions manage shared atmospheric challenges.

Global Cooperation in Climate Governance

The Need for International Action

The atmosphere is a global commons, meaning no single country owns or controls it. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions cross borders, making unilateral solutions ineffective. Shared responsibility ensures that all nations contribute to stabilising the climate system.

Global cooperation reduces the risk of “free riders” — countries benefiting from others’ actions without reducing their own emissions.

Long-term sustainability requires legally binding commitments, monitoring mechanisms, and inclusive governance structures.

Key International Institutions

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

UNFCCC: An international treaty established in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit, designed to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.

The UNFCCC provides the overarching legal and institutional framework. Nearly every country is a party to this convention, reflecting near-universal recognition of the climate issue.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

IPCC: A scientific body established in 1988 by the UN and WMO, tasked with assessing scientific knowledge on climate change, impacts, and potential adaptation/mitigation strategies.

The IPCC does not conduct new research but compiles and evaluates peer-reviewed science. Its Assessment Reports are central to policy negotiations, shaping international agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

Conferences of the Parties (COP)

Purpose and Process

The COP is the supreme decision-making body of the UNFCCC, meeting annually to evaluate progress and negotiate new commitments. Each COP brings together governments, scientists, NGOs, and businesses.

Plenary session at a UN climate conference (COP), where Parties, observers, and the secretariat convene to negotiate decisions under the UNFCCC. The image conveys the scale and inclusive participation characteristic of COP processes. Source.

Negotiations involve targets for emissions reduction, climate finance, and technological cooperation.

Consensus-based decision making ensures all nations, regardless of size or wealth, have a voice.

Milestone Agreements

Kyoto Protocol (1997): First legally binding GHG reduction commitments, focusing on industrialised nations.

Paris Agreement (2015): A global pact to limit warming to “well below 2°C” above pre-industrial levels, with ambitions for 1.5°C. Each country submits Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

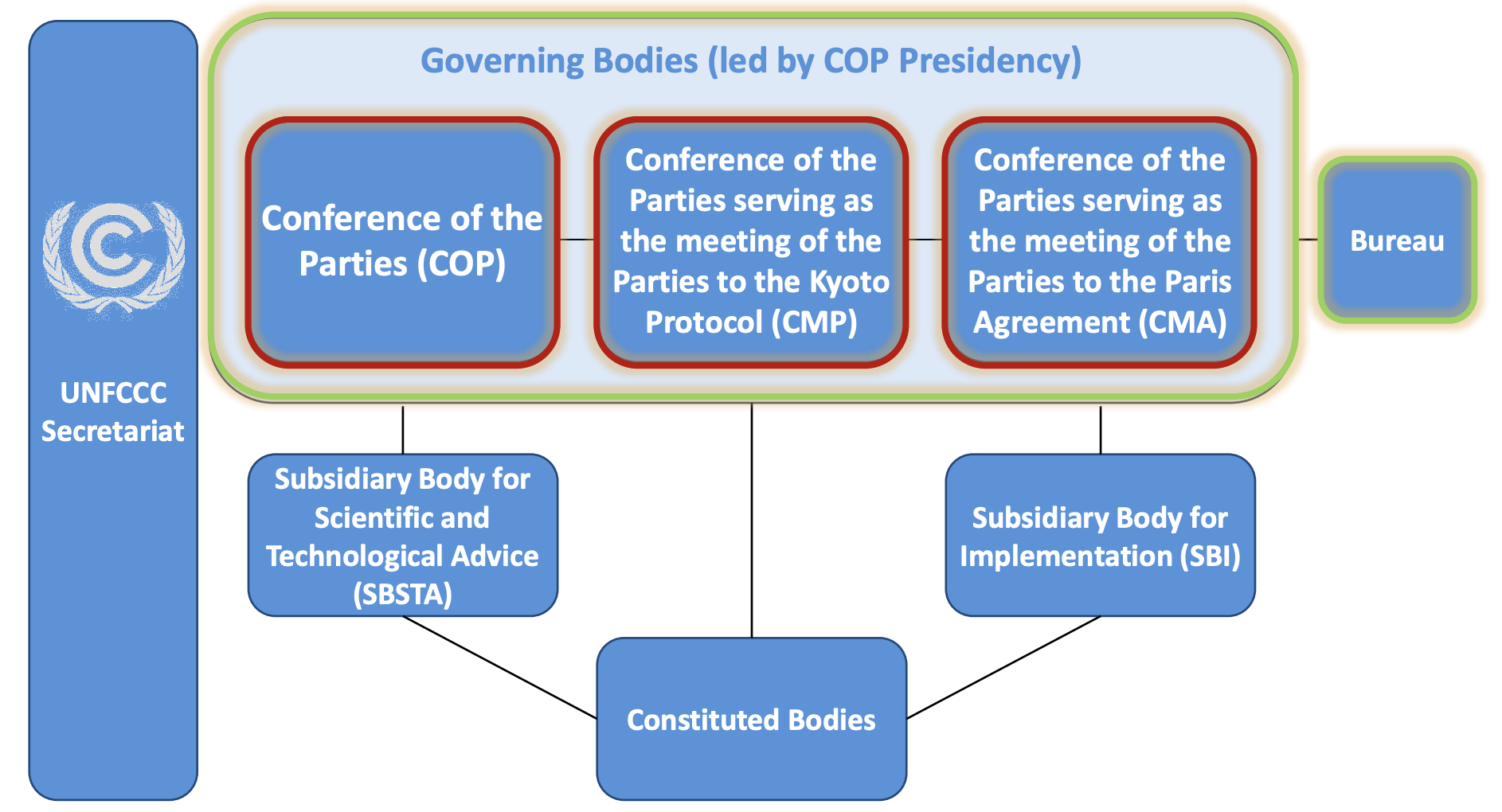

Diagram of the UNFCCC’s governance, including COP (and its parallel bodies for Kyoto and Paris), SBSTA, SBI, constituted bodies, and the secretariat. It clarifies decision-making pathways and the science–policy interface supporting COP outcomes. Extra detail: the diagram also shows the CMP (Kyoto Protocol body), which is beyond the Paris-era focus but helps contextualise the governance lineage. Source.

Mechanisms for Cooperation

Protocols and Treaties

Treaties provide legal accountability and frameworks for monitoring, reporting, and verification of emissions. Protocols are extensions of broader treaties, often specifying binding obligations.

Carbon Pricing Across Borders

Carbon pricing: A market-based approach that assigns a cost to emitting GHGs, incentivising reductions through taxes or emissions trading systems.

Cross-border carbon pricing could harmonise economic policies, reduce competitive disadvantages, and strengthen collective mitigation. Examples include the EU Emissions Trading System and proposed carbon border adjustment mechanisms.

Governance Challenges

Divergent National Interests

Developed countries, historically responsible for most emissions, are often expected to take the lead.

Developing nations argue for climate justice, highlighting their right to economic growth and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR).

Financing and Technology Transfer

Developing nations need financial and technological support to implement low-carbon strategies. The Green Climate Fund was established to channel resources, but contributions remain contested.

Enforcement and Compliance

Treaties rely heavily on voluntary compliance. Unlike domestic laws, international agreements lack strong enforcement mechanisms. Peer pressure, diplomatic pressure, and global monitoring by bodies like the IPCC help encourage compliance.

Case Study: Paris Agreement Governance

The Paris Agreement represents a flexible governance model:

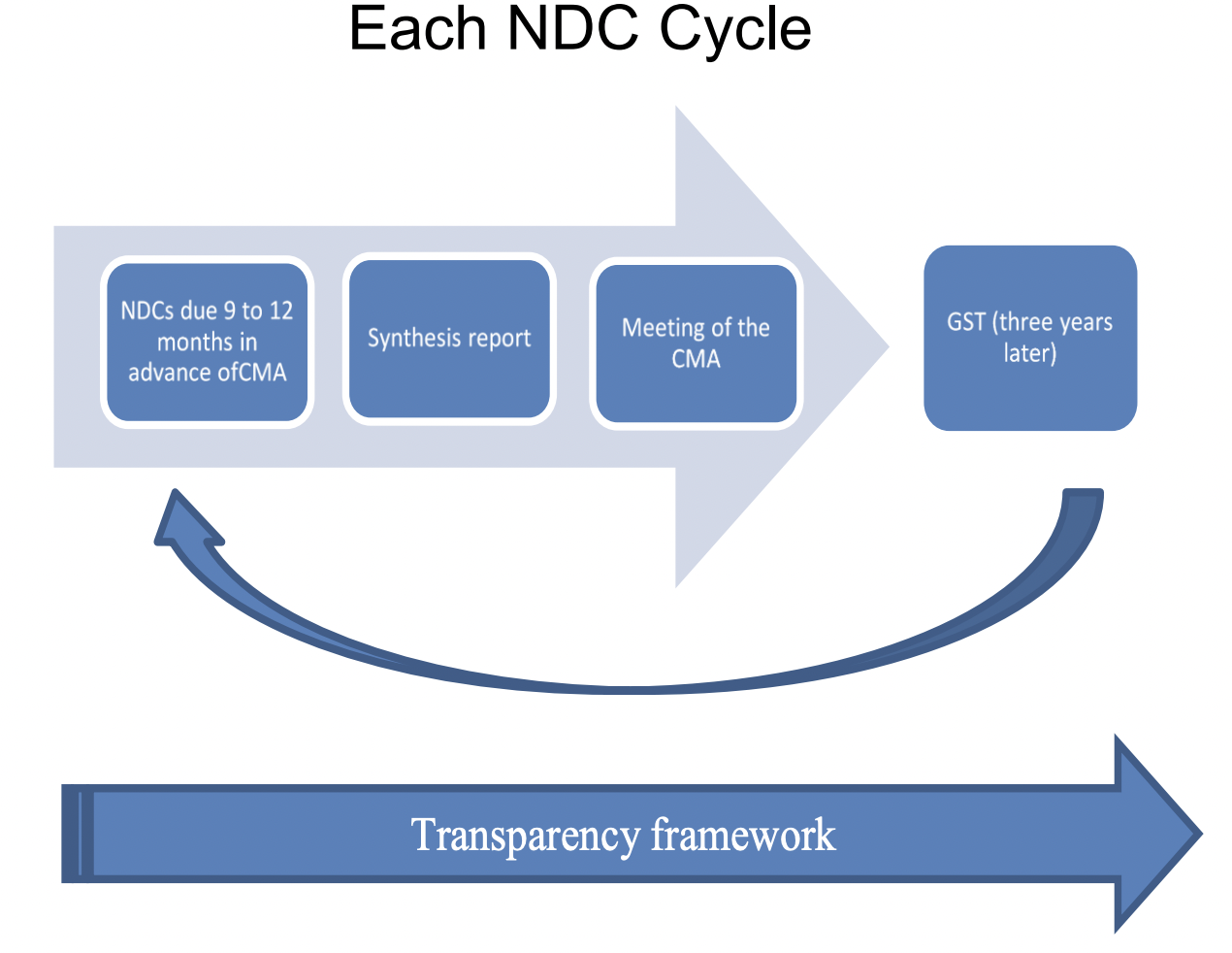

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) allow countries to set their own targets, reviewed every five years.

The Paris Agreement’s NDC cycle: Parties submit NDCs 9–12 months before the CMA; the secretariat prepares a synthesis report; the CMA meets; the Global Stocktake follows, all under the transparency framework. This figure reinforces the ratchet-mechanism students need to recall. Source.

A transparency framework ensures countries report progress openly.

Unlike Kyoto, it covers both developed and developing nations, promoting inclusivity.

This flexibility strengthens participation but can weaken ambition if targets are not rigorous.

The Role of Civil Society and Non-State Actors

NGOs and Advocacy

Non-governmental organisations play an essential role in pressuring governments, monitoring compliance, and raising public awareness.

Business and Finance Sectors

Private companies are increasingly part of the solution, adopting carbon disclosure, investing in renewables, and engaging in global initiatives like the Science Based Targets initiative.

Youth and Grassroots Movements

Movements such as Fridays for Future highlight intergenerational equity and push governments towards more ambitious commitments.

The Future of Global Governance

Strengthening Cooperation

To stabilise GHG concentrations and prevent dangerous climate change, future governance may include:

Expansion of cross-border carbon pricing mechanisms.

Greater climate finance commitments.

Integration of climate policy with trade and development goals.

Role of Science and Monitoring

The IPCC will remain central in synthesising evidence. Improved climate models, satellite monitoring, and open data access enhance transparency and accountability.

FAQ

The UNFCCC provides the legal and political framework for international cooperation, organising negotiations and agreements.

The IPCC functions as a scientific advisory body, compiling peer-reviewed research and providing reports that shape the negotiations under the UNFCCC.

NDCs allow each country to set its own emissions reduction targets based on national circumstances.

They ensure flexibility while still requiring all parties to participate, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, which applied mainly to developed nations.

Every five years, NDCs are reviewed and expected to become progressively more ambitious, creating a “ratchet mechanism” for stronger global action.

Consensus ensures all parties agree before adopting a decision, giving equal weight to both large and small nations.

This process promotes inclusivity but can slow negotiations, as a single country may block proposals.

While it builds legitimacy, critics argue it sometimes results in weaker, compromise-driven outcomes.

EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS): The world’s largest carbon market, covering multiple member states.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAM): Proposed by the EU to prevent “carbon leakage” by imposing tariffs on imports with high emissions.

Such mechanisms encourage uniformity across borders and reduce competitive disadvantages for regions implementing strong climate policies.

Developing nations often form negotiation blocs, such as the G77 + China, to amplify their voices.

They highlight issues of equity, calling for climate justice, financial support, and technology transfer from developed nations.

Their participation ensures that agreements account for diverse vulnerabilities and development needs, strengthening legitimacy and fairness in global cooperation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State two roles of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in global climate governance.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each correct role stated (max 2).

Acceptable answers include:Compiles and assesses peer-reviewed scientific research on climate change.

Produces Assessment Reports that inform international negotiations.

Provides scientific evidence for treaties such as the Kyoto Protocol or Paris Agreement.

Advises policymakers with summaries of scientific consensus.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how the Paris Agreement strengthens global cooperation on climate change compared to the Kyoto Protocol.

Mark Scheme:

Up to 2 marks for outlining key limitations of Kyoto Protocol (e.g., binding only for developed nations, limited global coverage).

Up to 2 marks for explaining inclusivity of the Paris Agreement (covers both developed and developing nations, Nationally Determined Contributions).

1 mark for additional valid detail (e.g., transparency framework, five-year review cycle, long-term temperature goals of below 2°C and ideally 1.5°C).

Maximum: 5 marks.