IB Syllabus focus:

‘Shift from fossil energy to renewables; set and meet carbon-neutrality dates across sectors and nations.’

Decarbonisation and carbon neutrality are central to international climate strategies. By reducing fossil fuel use and adopting renewable energy, nations aim to stabilise atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and meet agreed neutrality targets.

Decarbonisation Explained

Decarbonisation refers to the systematic reduction of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across all sectors of the economy. This is primarily achieved by:

Transitioning away from fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas.

Expanding the use of renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal.

Improving energy efficiency in buildings, transport, and industry.

Developing low-carbon technologies including hydrogen energy and carbon capture.

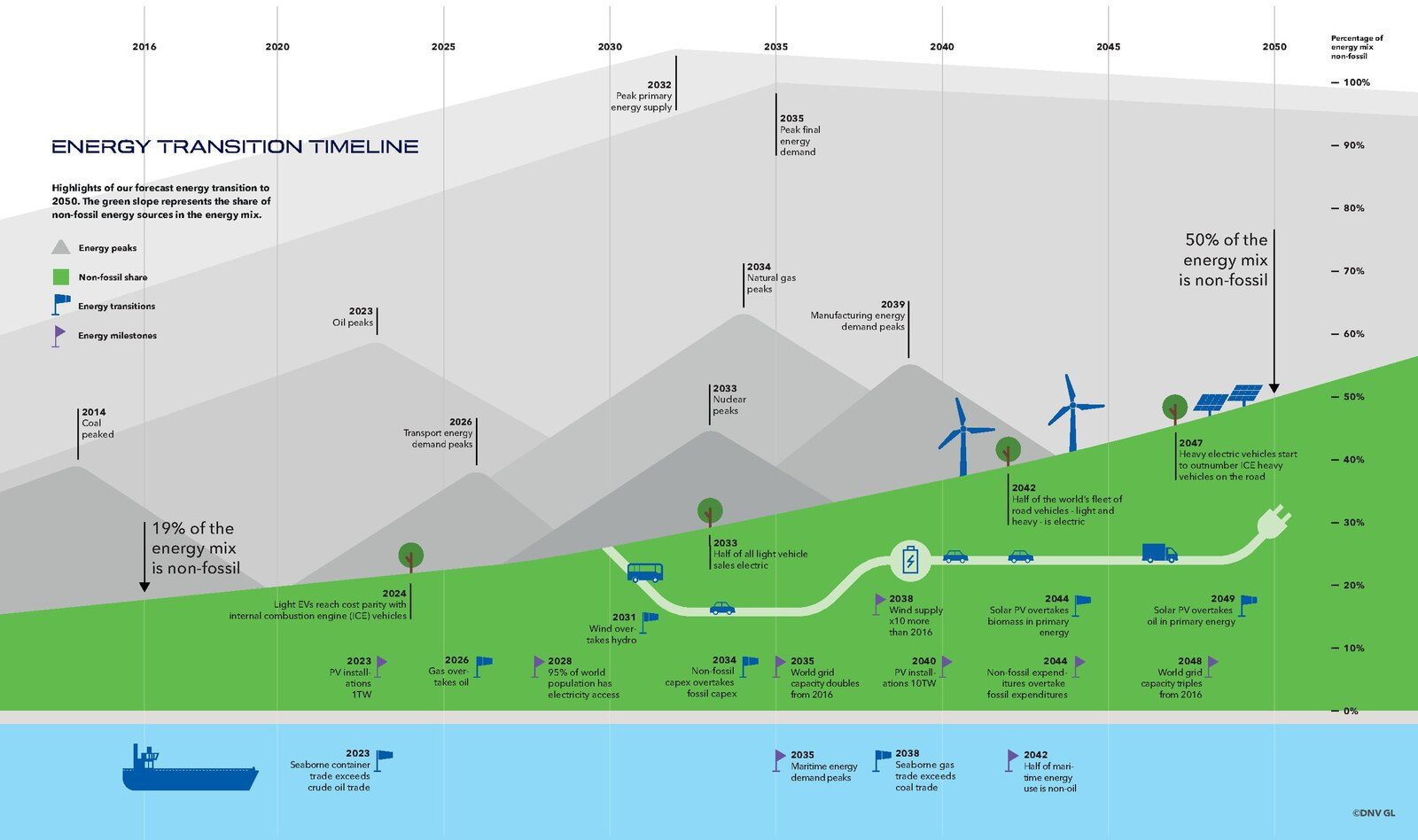

Projected global energy transition showing declining fossil share and rising non-fossil sources through 2050. The timeline reinforces why decarbonisation requires structural energy-mix change. Forecast milestones are illustrative and may include extra sectoral detail beyond this syllabus focus. Source.

Decarbonisation: The process of reducing carbon emissions from human activities to achieve lower net greenhouse gas outputs.

Decarbonisation is essential for limiting the enhanced greenhouse effect, which is driven by human emissions of CO₂, methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O).

Carbon Neutrality Targets

Carbon neutrality occurs when the total amount of GHGs emitted is balanced by an equal amount removed or offset. Many countries, cities, and corporations have pledged to achieve this balance by specific dates.

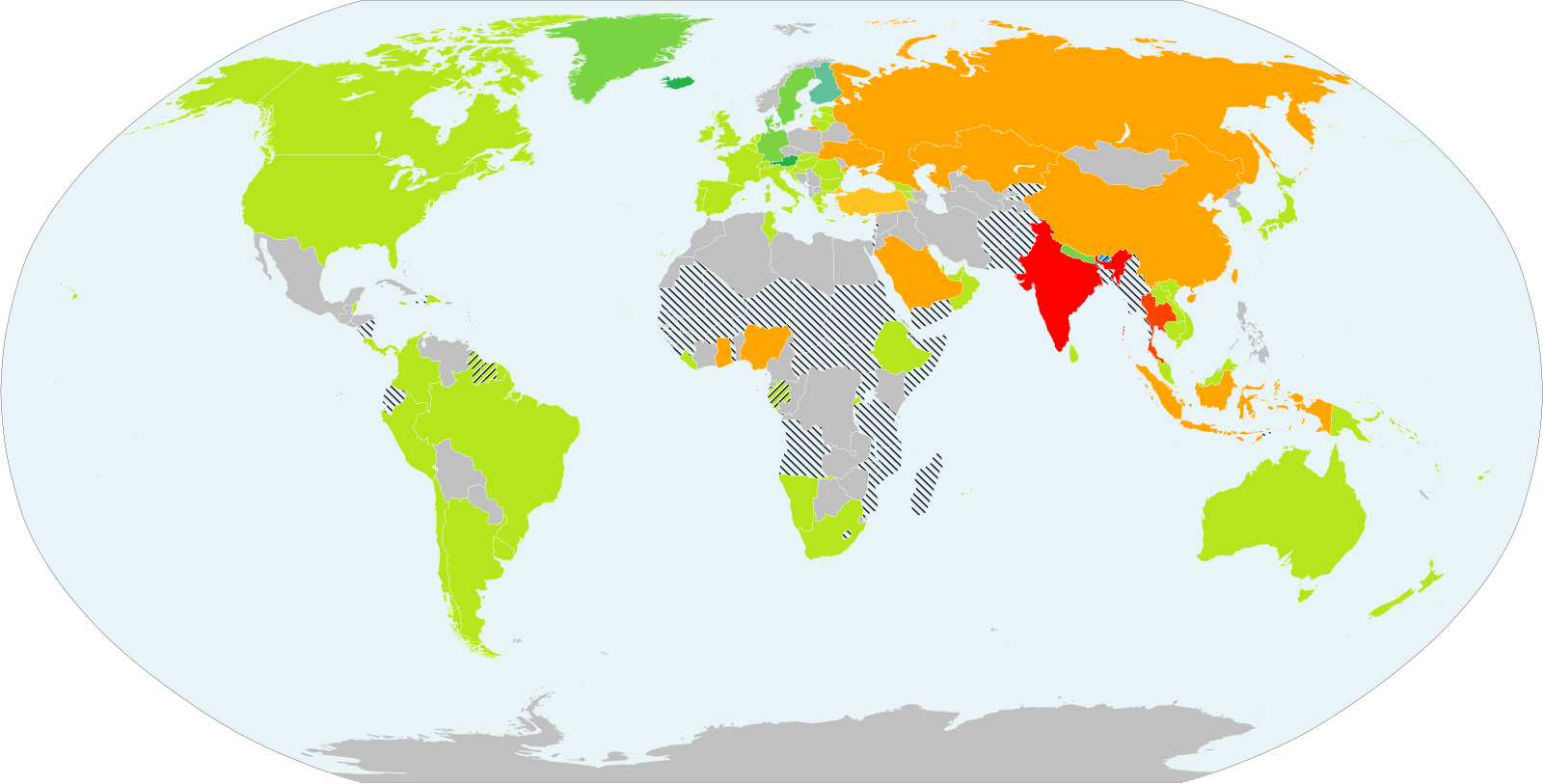

World map showing countries’ stated target years for climate neutrality or net-zero. This visual highlights the spread of national neutrality dates referenced in the notes. Colours group intended years and indicate status categories as defined by the source. Source.

Carbon neutrality: A state where net greenhouse gas emissions are zero, achieved by balancing emissions with removal or offsets.

Key global neutrality targets include:

The European Union aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050.

China targeting carbon neutrality by 2060.

Many smaller nations aiming for neutrality as early as 2035–2040.

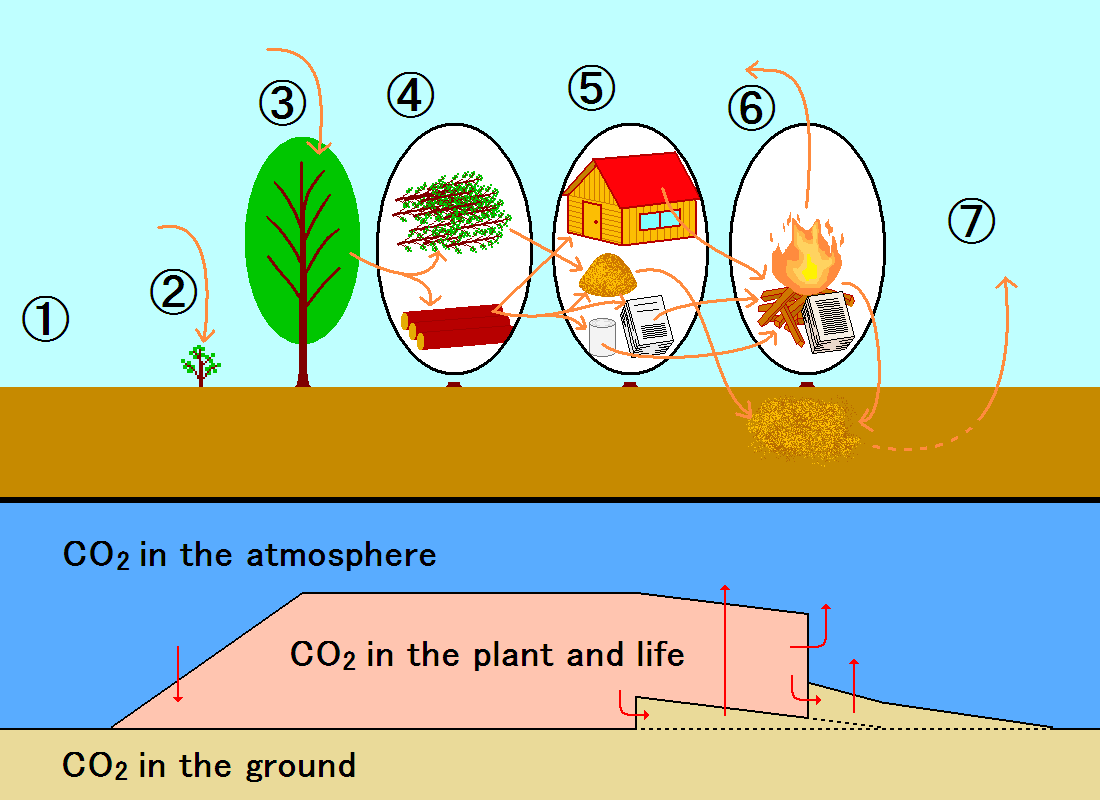

Simplified carbon-cycle schematic illustrating how biological uptake and subsequent release can balance emissions to achieve neutrality. The panel includes additional life-cycle steps for plant products that go beyond the syllabus scope but clarify the balance principle. Labels identify atmospheric, biotic, and ground carbon pools. Source.

Strategies to Achieve Neutrality

Renewable energy deployment: Expanding solar, wind, and hydropower.

Transport transition: Promoting electric vehicles and low-carbon public transport.

Agricultural reform: Reducing methane from livestock, improving soil management, and enhancing carbon sequestration.

Reforestation and afforestation: Expanding natural carbon sinks.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS): Technologies designed to remove CO₂ directly from industrial emissions or the atmosphere.

Sector-Wide Transformation

Decarbonisation requires structural changes across key sectors:

Energy Sector

Phasing out coal power plants and preventing new fossil-based infrastructure.

Expanding decentralised renewable grids.

Introducing smart-grid technologies to balance intermittent renewables.

Transport Sector

Electrification of cars, buses, and rail systems.

Shifts towards active transport modes such as cycling and walking.

Sustainable aviation initiatives, including biofuels and electric aircraft prototypes.

Industrial Sector

Switching to renewable-powered manufacturing processes.

Using green hydrogen as a substitute for fossil fuels in heavy industry.

Recycling and circular economy strategies to minimise raw material extraction.

Built Environment

Retrofitting older buildings for efficiency.

Enforcing zero-emission building codes for new developments.

Using sustainable materials such as timber and low-carbon cement alternatives.

Global Frameworks and Agreements

International agreements guide neutrality commitments. The Paris Agreement (2015) requires nations to submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to reduce emissions. These pledges are often tied to neutrality dates, setting measurable progress pathways.

Additionally, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings provide global platforms for accountability.

Importance of Timelines

Neutrality targets provide clear milestones for progress. Without them, decarbonisation can lack urgency. Timelines such as 2050 neutrality goals are used to:

Encourage policy continuity.

Drive innovation in low-carbon technologies.

Attract finance for renewable energy projects.

Challenges and Barriers

Despite ambition, achieving neutrality faces barriers:

Financial constraints in developing nations.

Political resistance and vested fossil fuel interests.

Technological gaps in carbon removal and storage.

Equity concerns, as richer nations may achieve neutrality faster while poorer ones face adaptation challenges.

Climate Justice Dimension

Carbon neutrality is not only technical but also ethical. Nations with historically high emissions face greater responsibility for early decarbonisation. Meanwhile, developing countries demand financial and technological support to meet their targets. This reflects the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities embedded in international law.

Conclusion of Focus Area

The IB syllabus highlights the shift from fossil energy to renewables and the need to set and meet neutrality targets across sectors and nations. Students must understand that these actions are essential for stabilising the climate system, reducing human-induced warming, and ensuring a sustainable future.

FAQ

Decarbonisation is the process of reducing carbon emissions by replacing fossil fuels with renewables, improving efficiency, and adopting low-carbon technologies.

Carbon neutrality refers to achieving a balance between emissions produced and emissions removed or offset, often by a set target year. Decarbonisation is a key pathway to achieving neutrality.

Countries set targets based on factors such as economic capacity, current energy dependence, technological readiness, and political will.

Developed nations with greater financial and technological resources often set earlier targets.

Developing nations may set later targets to allow for continued economic growth while transitioning gradually.

Targets act as milestones that shape policy in energy, transport, agriculture, and infrastructure.

Governments introduce subsidies for renewables, carbon pricing schemes, and stricter building codes.

They also create long-term climate plans to ensure accountability and progress monitoring.

Carbon offsets compensate for emissions that are difficult to eliminate. These include:

Reforestation and afforestation projects.

Investment in renewable energy in other countries.

Technological solutions such as carbon capture and storage.

Offsets are controversial if used excessively, as they may delay actual emission reductions.

Even with 2050 or 2060 targets, immediate action is necessary because:

Current emissions lock in long-term warming due to CO₂’s long atmospheric lifetime.

Early reductions reduce the need for drastic future cuts.

Delays risk crossing climate tipping points, making neutrality harder and more costly to achieve.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term carbon neutrality and explain why it is significant in the context of climate change.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for an accurate definition of carbon neutrality: net zero greenhouse gas emissions achieved by balancing emissions with removals or offsets.

1 mark for explaining significance: important as it sets a measurable goal for reducing human contribution to climate change.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss two strategies that nations can use to achieve carbon neutrality, and evaluate one challenge that may limit their effectiveness.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks: Identification and explanation of the first strategy (e.g., renewable energy deployment, transport electrification, reforestation, carbon capture).

1–2 marks: Identification and explanation of the second strategy.

1 mark: Evaluation of a challenge (e.g., financial costs, political resistance, technological gaps, equity concerns) explaining how it may limit effectiveness.

(Maximum 5 marks. Candidates must cover both strategies and provide one evaluative point to access full marks.)