IB Syllabus focus:

‘Natural resources and ecosystems form natural capital; their goods and services are natural income. Treating nature as ‘capital’ is contested but useful for managing sustainable use.’

Natural resources underpin all human societies, providing essential materials and processes. The concept of natural capital allows us to measure, manage, and sustain these resources for present and future generations.

Understanding Natural Resources and Natural Capital

Natural Resources

Natural resources include all materials and processes that occur in the environment and are useful to humans. These range from timber and freshwater to soil fertility and clean air. Some are tangible goods, while others are less visible ecosystem services.

Natural Capital

Natural Capital: The stock of natural resources and ecosystems that provide goods and services of value to people.

Natural capital includes ecosystems, species, and geological resources. These stocks generate flows of benefits, both material (e.g., food, minerals, timber) and non-material (e.g., climate regulation, aesthetic value).

Natural Income

Linking Capital and Income

Natural Income: The annual yield of goods and services obtained from natural capital.

Examples include:

Timber harvested from forests.

Freshwater supplies replenished annually by rainfall.

Fish caught sustainably from ocean stocks.

Carbon sequestration by forests and wetlands.

Like financial capital producing interest, natural capital provides flows of natural income that support human well-being.

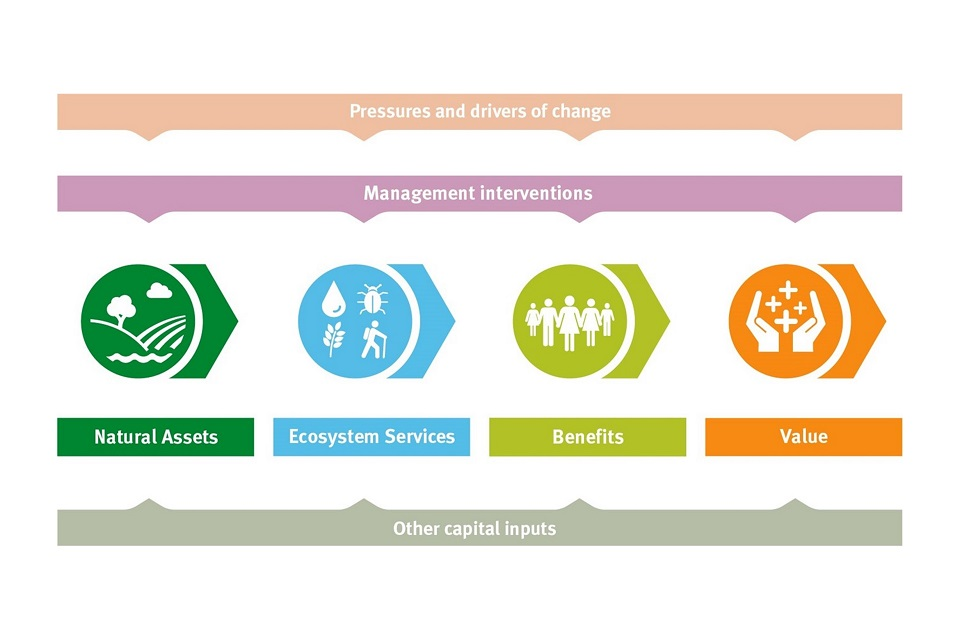

Natural capital (assets) generates flows of ecosystem services, which translate into human benefits and value over time. The simple left-to-right flow mirrors the stock-to-income framing used to manage sustainability. Labels are streamlined to emphasise the sequence rather than technical detail. Source.

The Contested Idea of “Nature as Capital”

Why the Concept is Used

Treating nature as capital provides:

A framework to evaluate sustainability.

Tools for measuring resource use against regeneration.

Economic language that policymakers and businesses understand.

This framing helps integrate environmental considerations into economic decision-making.

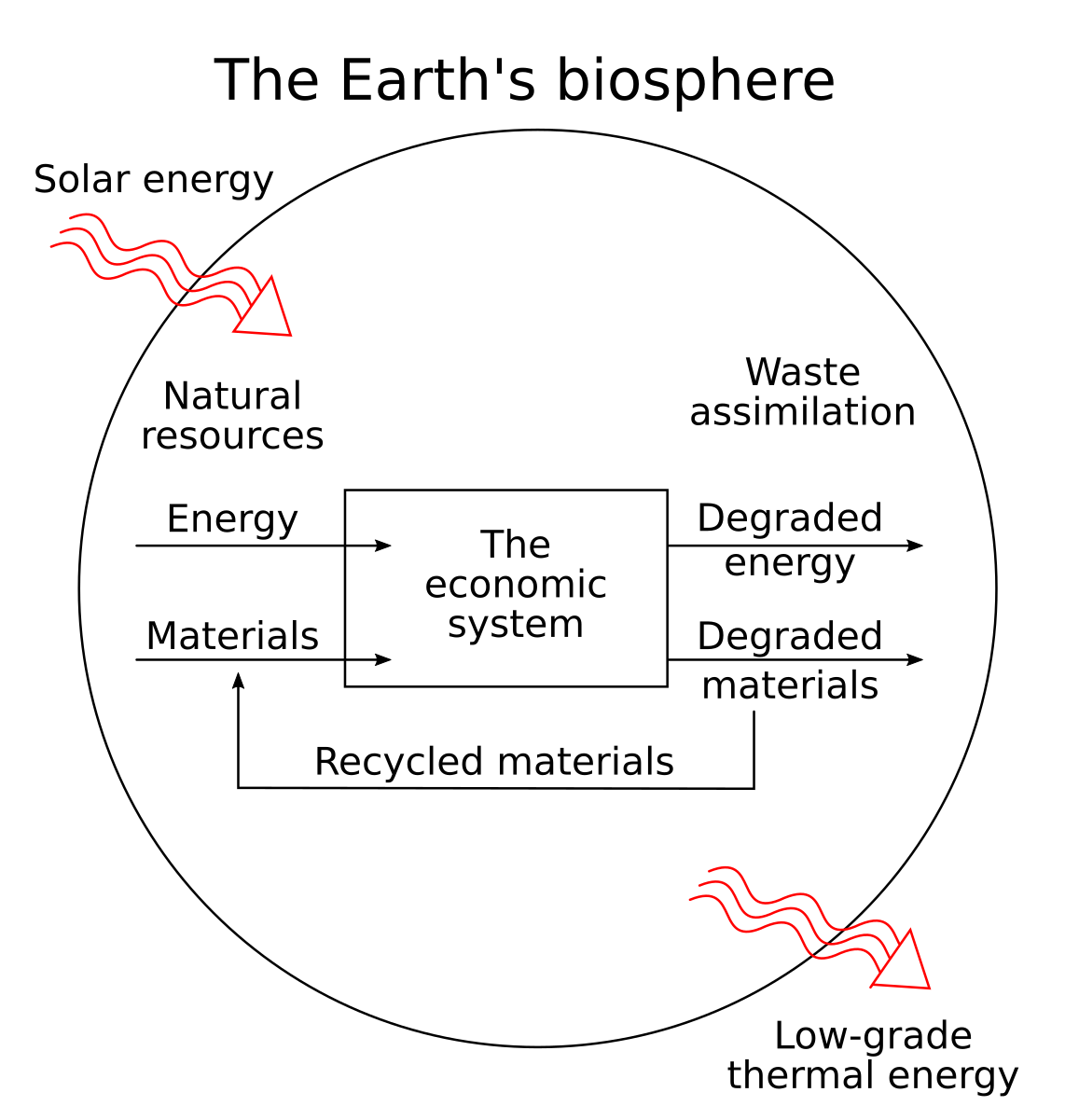

The diagram shows valuable natural resources entering the economy, being transformed into goods, and eventually leaving as waste and pollution, with recycling requiring additional inputs. It visually connects environmental stocks to economic flows, supporting the capital–income model. The simple icons and arrows keep attention on processes, not detail. Source.

Criticisms of the Concept

However, the term is controversial because:

It reduces nature to economic terms, ignoring intrinsic and cultural values.

It risks encouraging commodification of ecosystems.

It can obscure ethical obligations to preserve biodiversity beyond human benefit.

Types of Natural Capital

Natural capital can be categorised into distinct forms:

Renewable natural capital: Resources that regenerate within human lifespans, such as forests, fish, or soil fertility.

Non-renewable natural capital: Finite resources that do not regenerate on human timescales, including fossil fuels and minerals.

Ecosystem services: Processes provided by ecosystems, such as pollination, flood regulation, and nutrient cycling.

Abiotic resources: Non-living resources such as sunlight, wind, and water currents.

Each type contributes differently to natural income.

Ecosystem Goods and Services

Goods

These are physical, tangible products from ecosystems:

Timber

Freshwater

Crops

Fish

Services

These are functions and processes that support life and human activities:

Climate regulation through carbon sequestration.

Soil formation and fertility maintenance.

Flood control and water purification.

Pollination of crops by insects.

Both goods and services form essential components of natural income.

Measuring and Valuing Natural Capital

Quantitative Assessment

Natural capital can be measured in terms of:

Physical units: e.g., cubic metres of timber or tonnes of fish.

Economic value: assigning monetary worth to ecosystem services.

Limitations of Valuation

Difficulties exist in valuing intangible services (e.g., spiritual or cultural significance).

Economic valuations may underestimate biodiversity’s long-term ecological importance.

Ethical concerns arise over placing monetary value on life-supporting systems.

Sustainability and Natural Capital

Sustainable Yield

Sustainable Yield: The level of resource use that allows natural capital to regenerate and continue providing natural income indefinitely.

Overexploitation leads to degradation, reducing the stock of natural capital and threatening long-term human well-being.

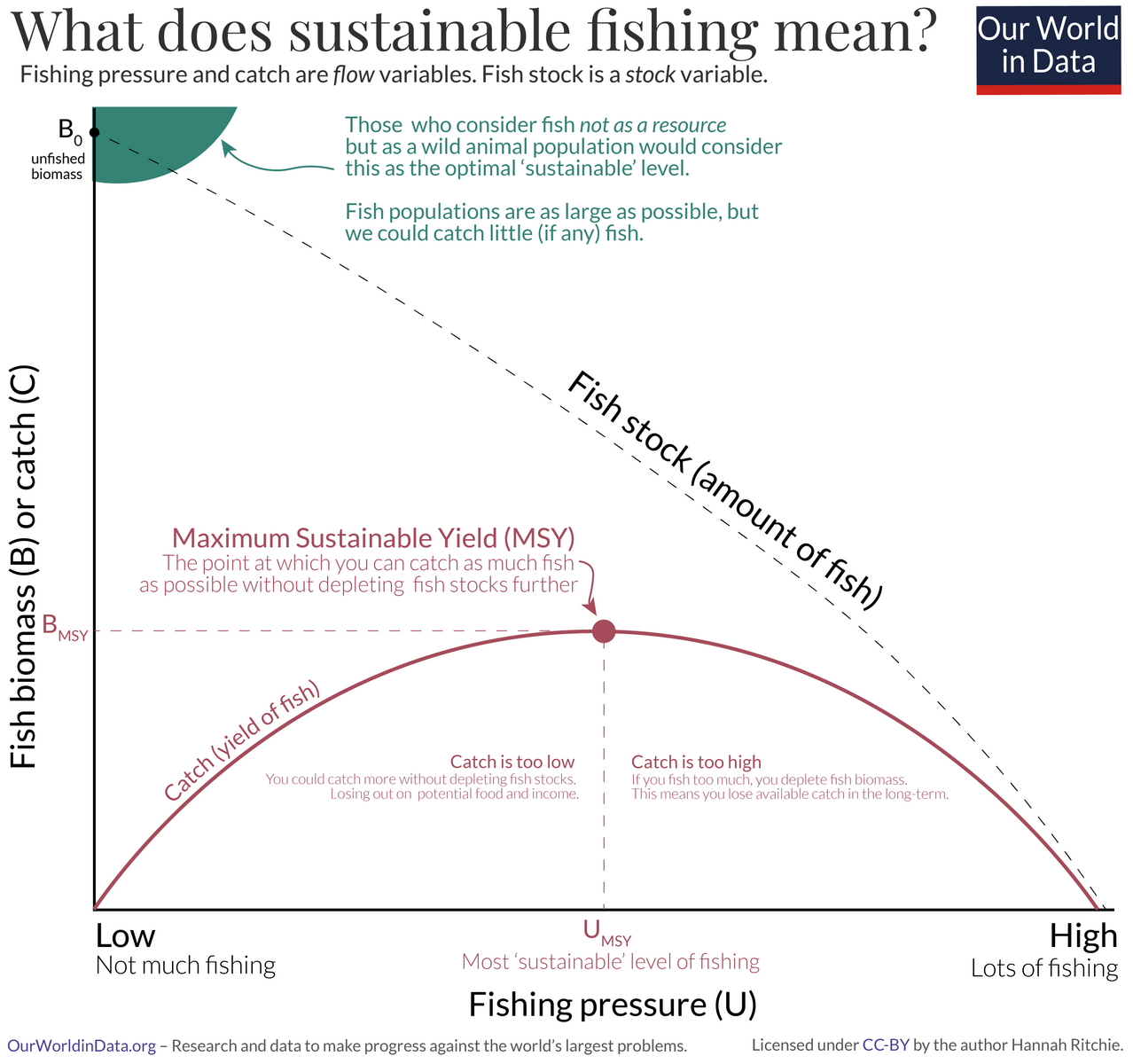

The curve illustrates maximum sustainable yield (MSY)—the highest long-run harvest that does not reduce the renewable capital stock. It highlights how yield rises with exploitation up to an optimum and then falls as stocks are degraded. Although the example is fisheries, the stock-and-flow logic applies to other renewable resources. Source.

Examples

Overfishing depletes stocks, converting renewable resources into effectively non-renewable ones.

Deforestation beyond regrowth capacity reduces forest ecosystem services.

Case for Treating Nature as Capital

Benefits

Encourages governments and corporations to account for environmental impacts.

Supports policies aimed at maintaining resource stocks for future generations.

Provides a bridge between ecological science and economic planning.

Risks

May lead to trade-offs that prioritise economic gain over ecological integrity.

Could reinforce unsustainable exploitation if poorly managed.

Key Points to Remember

Natural capital refers to environmental stocks; natural income refers to their annual flows.

Goods and services from ecosystems sustain societies and economies.

Framing nature as capital helps with sustainability planning but remains contested.

Overuse of natural capital leads to resource depletion and long-term insecurity.

FAQ

Natural capital refers specifically to environmental stocks like forests, soils, and ecosystems that provide goods and services.

Unlike human capital (skills, knowledge) or manufactured capital (machines, infrastructure), natural capital is finite, often irreplaceable, and underpins all other forms of capital. Its depletion directly affects the productivity of human and manufactured systems.

Some natural income flows are subtle or indirect, making them less visible in economic terms. Examples include:

Pollination by insects in wild habitats.

Carbon stored in peatlands and wetlands.

Soil nutrient cycling that supports agriculture.

Coastal mangrove protection from storm surges.

These services rarely appear in markets but have high ecological and social value.

Indigenous and local communities often hold spiritual, cultural, and relational values for land and ecosystems.

Framing nature as “capital” can conflict with worldviews that see the environment as kin or sacred rather than a resource. This tension highlights the risk of reducing nature to purely economic terms, overlooking intrinsic meanings and rights-based perspectives.

Measuring natural income provides a benchmark for sustainable use. By tracking annual yields:

Governments can set limits, e.g., fishing quotas.

Businesses can monitor extraction against regeneration rates.

Communities can identify early warning signs of decline.

Without such measures, exploitation often exceeds natural replacement, leading to long-term losses.

A key factor is whether regeneration occurs within a human timeframe.

Renewable capital regenerates in years to decades (e.g., forests, freshwater supplies).

Non-renewable capital takes geological time to form (e.g., fossil fuels, minerals).

If renewables are used faster than they regenerate, they effectively function as non-renewable within human planning horizons.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

Define the terms natural capital and natural income.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a correct definition of natural capital: stock of natural resources and ecosystems providing goods and services of value.

1 mark for a correct definition of natural income: annual yield of goods and services obtained from natural capital.

Question 2 (5 marks):

Discuss two advantages and two criticisms of treating nature as “capital” when managing environmental resources.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining two advantages:

Provides a framework for evaluating sustainability (1).

Allows measurement of use against regeneration (1).

Uses economic language that policymakers and businesses understand (1).

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining two criticisms:

Reduces nature to economic terms, ignoring intrinsic and cultural values (1).

Encourages commodification of ecosystems (1).

Can obscure ethical obligations to biodiversity (1).

1 mark for coherent discussion and balance between advantages and criticisms.