IB Syllabus focus:

‘Even renewable resources can be used unsustainably via extraction, transport or processing. Short-term economic incentives have depleted whales, fish stocks, forests, and more.’

Short-term exploitation of natural resources often leads to long-term ecological damage. Unsustainable extraction, transport, and processing undermine regeneration rates, threatening biodiversity and human survival.

Understanding Unsustainability

Unsustainability arises when resources are consumed at a rate or in a manner that prevents their natural recovery. Even resources considered renewable can become functionally non-renewable if overused.

Sustainability: The use of natural resources in ways and at levels that allow ecosystems to regenerate and continue providing goods and services for future generations.

Renewable vs Non-Renewable Misconceptions

Renewable resources like fish stocks, forests, or groundwater are often assumed to be inexhaustible.

Over-exploitation, habitat destruction, or pollution can permanently reduce their natural capital.

This mismanagement leads to resources that act non-renewably within human timescales.

Unsustainable Methods

Even when resources are renewable, unsustainable methods of extraction, transport, and processing create ecological and social harm.

Extraction Pressures

Overfishing: Driven by short-term economic gain, many fisheries collapse when catches exceed reproductive capacity.

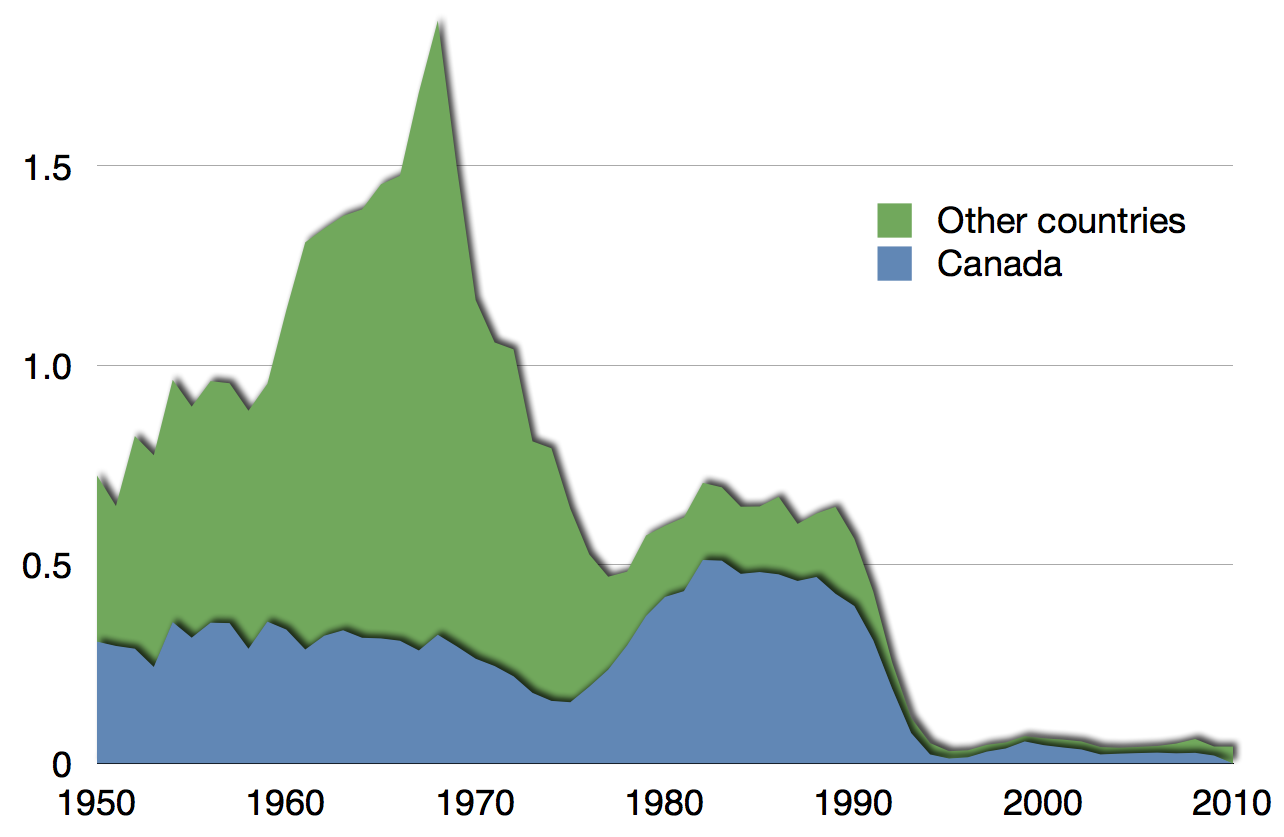

Time-series graph showing the dramatic decline and collapse of Atlantic northwest cod biomass following decades of overfishing that exceeded stock regeneration. The image exemplifies how short-term economic incentives can irreversibly degrade natural capital within policy-relevant timeframes. Source.

Deforestation: Clear-cutting for timber or agriculture outpaces forest regrowth, degrading ecosystems and releasing stored carbon.

Natural-colour satellite image of Amazon deforestation showing a characteristic “fishbone” pattern radiating from roads, where progressive clear-cutting fragments and degrades forest ecosystems. The visual links access expansion to accelerated extraction and long-term loss of natural capital. Source.

Whaling: Excessive hunting in the 19th and 20th centuries decimated whale populations, many of which have not fully recovered.

Transport Impacts

Transport of extracted goods involves carbon emissions and pollutant release.

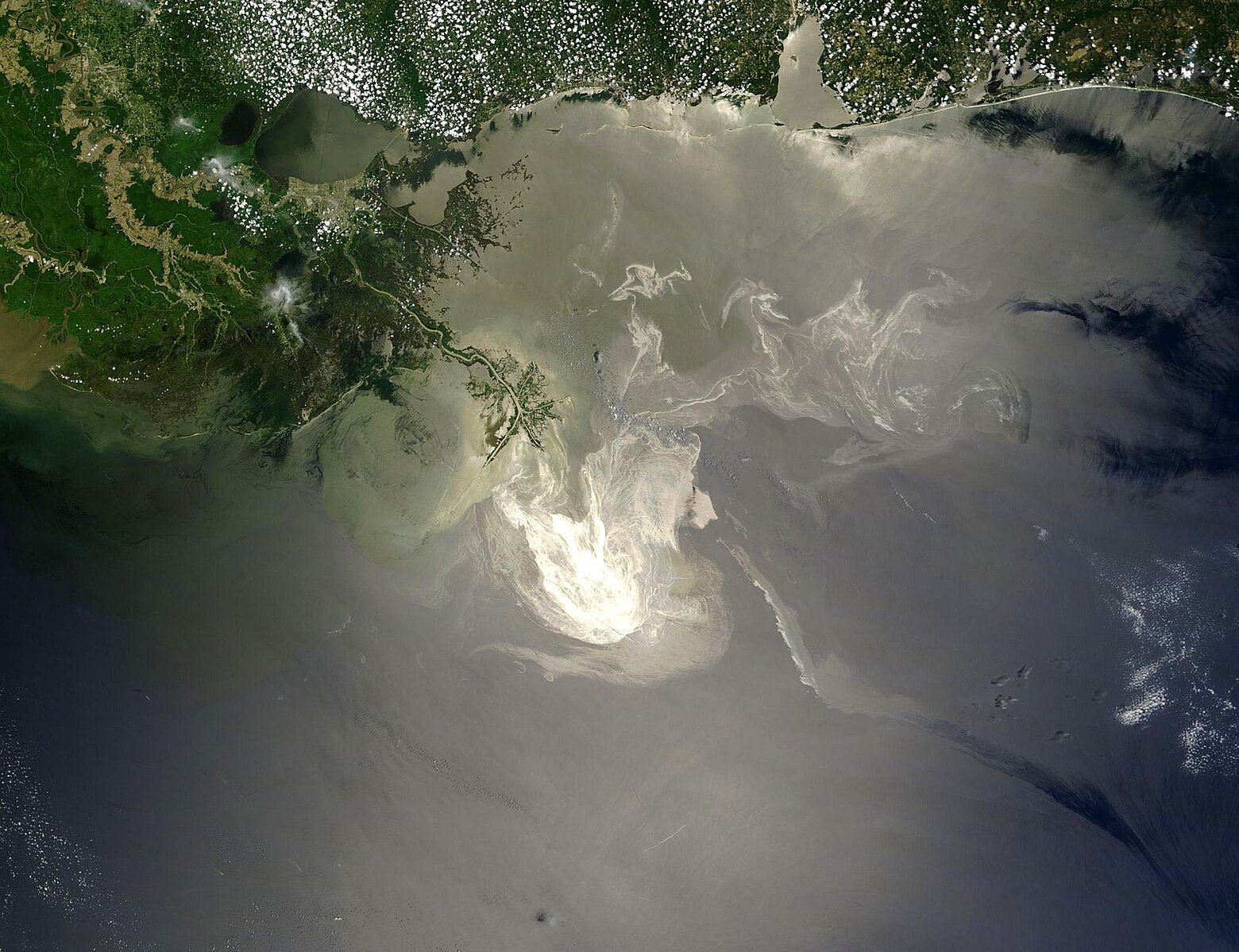

Oil spills during shipping devastate marine ecosystems, showing how transport processes threaten long-term ecological stability.

Satellite view of the Deepwater Horizon oil slick spreading across the Gulf of Mexico, illustrating the acute pollution risk from hydrocarbon extraction, transport, and processing. Such events impose long-lasting ecological and economic costs well beyond any short-term gains. Source.

Processing Effects

Resource refining often produces toxic waste by-products, polluting soils, water, and air.

Energy-intensive processing adds to greenhouse gas emissions, linking resource use to global climate change.

Short-Termism and Economic Incentives

Short-termism refers to prioritising immediate economic benefits over long-term sustainability.

Short-termism: A decision-making approach focused on immediate gains at the expense of future ecological, economic, or social stability.

Drivers of Short-Termism

Market demand: High-value commodities (like tropical hardwoods or fish delicacies) encourage overexploitation.

Profit motives: Companies often maximise extraction without accounting for ecological recovery.

Weak regulation: Lack of effective enforcement allows industries to ignore sustainable quotas.

Historical Examples

Whale oil once fuelled lamps globally until whale populations collapsed.

Cod fisheries in the North Atlantic were overfished to economic ruin.

Tropical deforestation continues for palm oil and beef, despite global concern.

Ecological Consequences

Unsustainable practices disrupt ecosystems in ways that often cannot be reversed.

Loss of biodiversity: Species extinction reduces ecosystem resilience.

Habitat destruction: Removal of forests, wetlands, and coral reefs eliminates essential ecosystem services.

Carbon cycle disruption: Deforestation and fossil-fuel-intensive processing elevate atmospheric CO₂.

Soil degradation: Overextraction of nutrients leads to desertification.

Social and Economic Consequences

While short-term gains benefit industries, societies suffer long-term costs.

Food insecurity: Collapse of fisheries reduces protein sources for millions.

Health risks: Pollution from processing contaminates water and air, impacting human health.

Economic collapse: Overreliance on depleted resources destabilises economies dependent on exports.

Inequality: Vulnerable communities bear the brunt of environmental degradation.

Factors Reinforcing Unsustainable Use

Unsustainability is not random; it stems from systemic pressures:

Global demand for cheap raw materials and energy.

Technological advances that increase extraction efficiency beyond sustainable limits.

Subsidies and incentives encouraging overuse rather than conservation.

Cultural factors such as viewing forests or oceans as limitless.

Pathways Towards Sustainable Management

Although this subsubtopic emphasises unsustainable methods, it is important to recognise that systems can be adjusted.

Setting quotas: Regulating harvest levels below regeneration rates.

Certification schemes: Labels like FSC (Forestry Stewardship Council) promote sustainable timber.

International agreements: Treaties such as the International Whaling Commission help curb overexploitation.

Education and awareness: Highlighting the dangers of short-termism influences consumer behaviour.

Key Takeaways

Even renewable resources become unsustainable if mismanaged.

Extraction, transport, and processing create risks beyond resource depletion.

Short-termism prioritises immediate profit but leads to long-term ecological and social harm.

Historical collapses of whales, fish stocks, and forests illustrate the consequences vividly.

FAQ

Technological advances can increase extraction efficiency to the point where renewable resources are harvested faster than their natural regeneration rates.

For example, industrial fishing fleets equipped with sonar and large trawlers can deplete fish stocks much more rapidly than traditional methods. Similarly, mechanised logging and road-building accelerate deforestation by granting access to previously remote forests.

While technology can also support sustainable management, its misuse often amplifies short-term exploitation.

Short-term economic incentives can erode traditional practices that once promoted sustainable use.

Communities that historically harvested resources seasonally or selectively may abandon these customs under pressure from commercial markets.

This shift can lead to cultural loss, as well as ecological damage, since traditional practices often evolved to align with natural regeneration cycles.

Subsidies can make overexploitation financially viable when it would otherwise be uneconomic.

Examples include:

Fuel subsidies for fishing fleets, allowing vessels to travel further and fish longer.

Agricultural subsidies that incentivise expansion into forested land.

These financial supports encourage short-term gains while masking the environmental costs of unsustainable practices.

When renewable resources are mismanaged, their long-term availability decreases, reducing future societies’ ability to meet demand.

Collapsed fish stocks reduce food security.

Lost forests limit timber, medicinal plants, and carbon storage.

Degraded soils reduce agricultural productivity.

Short-term exploitation compromises the resilience and capacity of ecosystems to provide for future generations.

Transport extends exploitation into previously inaccessible areas.

Road construction opens up forests to intensive logging and settlement. Shipping routes allow mass movement of extracted materials, but also risk accidents such as oil spills, which impose long-term ecological damage.

Thus, even without over-harvesting, the infrastructure of transport itself can lock societies into unsustainable practices.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain how a renewable resource can become unsustainable if used with short-term economic incentives.

Mark Scheme

1 mark for identifying that renewable resources can be depleted if used faster than they regenerate.

1 mark for linking this overuse to short-term economic incentives (e.g., overfishing for profit leading to stock collapse).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss two examples of unsustainable resource use that demonstrate the effects of short-termism.

Mark Scheme

Up to 2 marks for clearly describing each example (e.g., cod fisheries collapse, Amazon deforestation, whaling).

1 mark for explaining the short-term incentive behind each case (e.g., immediate profit, demand for commodities, fuel sources).

1 mark for linking each example to long-term consequences (e.g., ecosystem collapse, biodiversity loss, economic hardship).

Maximum 5 marks: balanced answers with clear connection between short-term actions and long-term impacts should be credited fully.