IB Syllabus focus:

‘Natural capital holds aesthetic, cultural, economic, environmental, health, intrinsic, social, spiritual and technological value. Values shift over time (e.g., coal ↓; lithium/cobalt ↑).’

Understanding how societies value natural capital is central to environmental management. Values assigned to nature influence decisions on conservation, resource use, and policy, and they continue to change with time.

Natural Capital and Its Many Values

The Concept of Natural Capital

Natural capital refers to the world’s stock of natural resources—such as forests, soils, water, minerals, and biodiversity—that provide goods and services. These resources generate natural income, meaning the flows of benefits humans receive from ecosystems.

Natural Capital: The stock of natural resources and ecosystems that provide goods and services, directly or indirectly supporting human well-being.

Societies attach different types of value to natural capital, influencing how these resources are managed and prioritised.

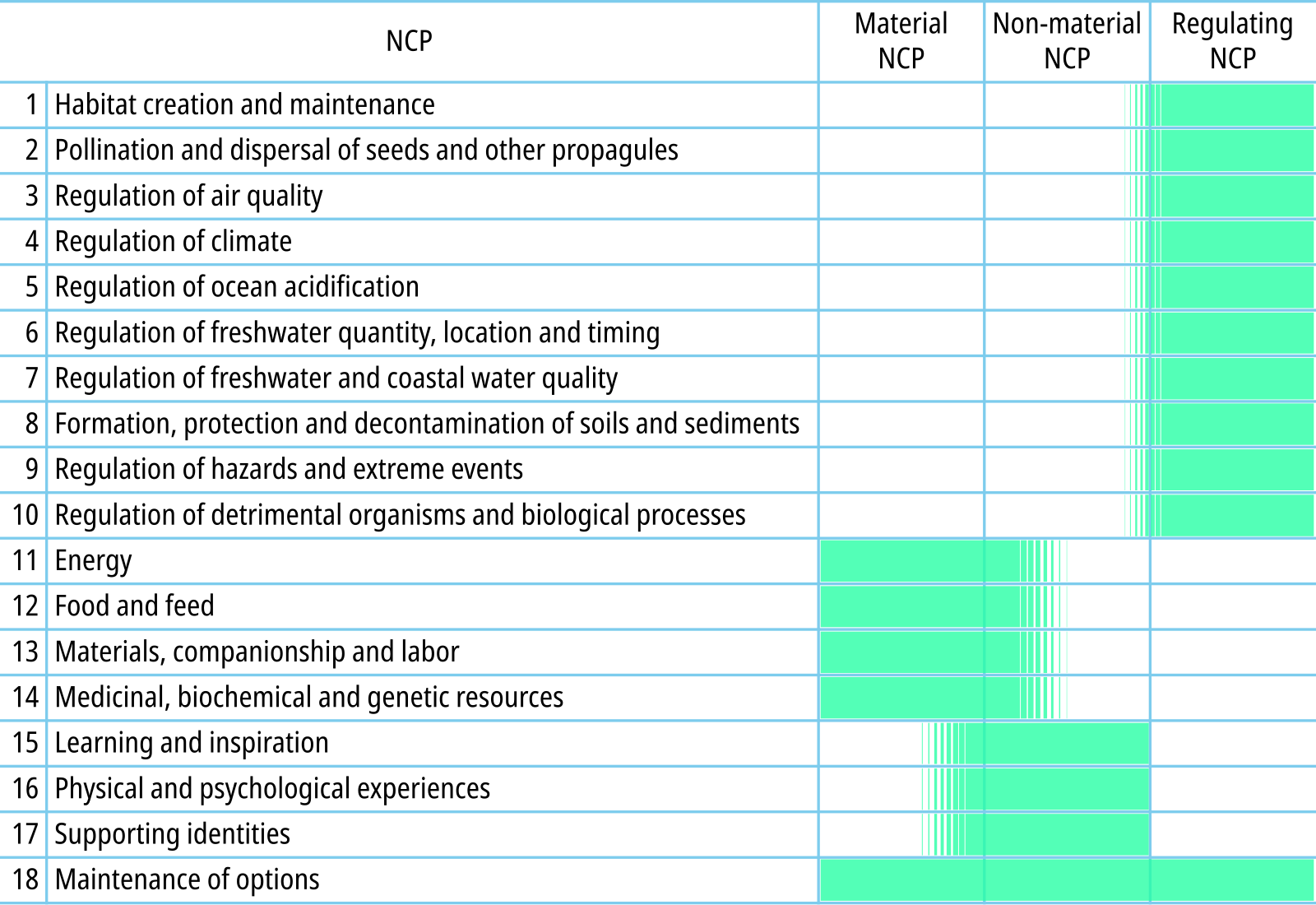

This diagram from IPBES maps “nature’s contributions to people,” showing how ecosystems underpin material, regulating, and non-material benefits that societies value. It directly aligns with aesthetic, cultural, economic, environmental, health, intrinsic, social, spiritual, and technological dimensions discussed in the notes. Source.

Types of Values in Natural Capital

Natural capital embodies multiple overlapping values. Each shapes human behaviour, policy-making, and global markets:

Aesthetic value: Appreciation of beauty in landscapes, wildlife, and ecosystems.

Cultural value: Importance tied to heritage, traditions, and identity.

Economic value: Market price of goods and services derived from ecosystems (timber, fisheries, minerals).

Environmental value: Contribution to maintaining ecosystem integrity and biodiversity.

Health value: Benefits to physical and mental well-being, such as clean air, water, and access to green spaces.

Intrinsic value: The belief that nature has worth independent of human use.

Social value: Shared benefits like recreation, tourism, and community identity.

Spiritual value: Connection between nature and belief systems or worldviews.

Technological value: Role of resources in advancing innovation (e.g., lithium for batteries, rare earths for electronics).

Changing Values Over Time

Historical Shifts in Valuation

The way societies value natural capital is not static. Changes occur due to technological development, shifting priorities, economic pressures, and cultural transitions.

Coal: Once central to the industrial revolution and global economic growth, coal is now valued less due to environmental costs and the rise of renewable alternatives.

This Our World in Data chart shows the share of primary energy consumption from coal over time, allowing students to visualise declining reliance in many contexts. It exemplifies how societal and policy priorities can lower the perceived value of coal. Source.

Whales: Hunted for oil in the past, whales are now valued more for conservation, tourism, and ecological roles.

Forests: Formerly exploited for land and timber, today increasingly valued for carbon sequestration and biodiversity protection.

Lithium and cobalt: Demand has increased dramatically in the 21st century as key components of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

This Our World in Data chart shows global lithium production over time, illustrating rapidly increasing output as battery technologies scale. It reinforces how technological change elevates the perceived value of specific minerals. Source.

Factors Driving Change

Several key drivers explain why the perceived value of natural capital evolves:

Economic shifts: Scarcity, market prices, and new industries alter demand.

Technological innovation: Advances create demand for specific materials (e.g., silicon in microchips).

Cultural awareness: Global movements highlight intrinsic and spiritual values of nature.

Environmental crises: Climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution heighten awareness of non-market values.

Political decisions: Policies and regulations reflect changing priorities (e.g., carbon taxes, subsidies for renewables).

Contesting the Valuation of Nature

Debates on Treating Nature as Capital

Framing ecosystems as capital has both advantages and criticisms.

Advantages

Provides a framework for economic analysis and sustainable management.

Makes resource values comparable across societies.

Encourages long-term thinking by linking natural income to sustainability.

Criticisms

Risks commodifying nature, reducing complex ecosystems to monetary terms.

Overlooks intrinsic or spiritual values that cannot be quantified.

Fails to reflect the full interdependence of ecological systems.

Natural Income: The flow of goods and services (such as timber, fish, or clean water) provided by natural capital over time.

Case Studies of Value Change

Example: Fossil Fuels vs Renewables

Past: Oil and coal were valued primarily for energy security and industrial growth.

Present: Environmental impacts have reduced their perceived worth, while solar and wind energy are gaining both economic and cultural value.

Example: Rare Earth Elements

Once obscure, minerals like neodymium and cobalt are now vital for renewable energy and electronics, showing how technological change reshapes value perceptions.

Implications for Sustainability

Linking Value Shifts to Resource Management

Changing values influence how societies manage natural capital. As perceptions evolve:

Resources once exploited may become conserved (e.g., whale sanctuaries).

Policies may reflect new valuations (e.g., carbon credits).

Investments may shift to technologies reducing reliance on depleting resources.

This dynamic underscores the importance of recognising multiple values simultaneously, ensuring decisions are not based solely on short-term economic measures but also include long-term environmental and cultural priorities.

FAQ

Cultural values shape how societies prioritise natural capital. For example, sacred forests in parts of Asia are protected due to spiritual significance rather than economic worth.

These values can lead to long-term conservation practices where ecosystems are preserved for their cultural identity. Unlike economic measures, cultural values often provide protection that resists market pressures.

Intrinsic values, which recognise the worth of nature independent of human use, cannot easily be quantified in monetary or policy terms.

Governments often rely on economic metrics for decisions. Since intrinsic value cannot be measured in the same way, it risks being overlooked despite its ethical importance.

Technological innovation can create demand for previously undervalued resources. For instance, rare earth elements became critical with the rise of smartphones and renewable energy technologies.

At the same time, technology can reduce reliance on older resources, such as coal, by enabling renewable alternatives. These shifts demonstrate how technology redefines value hierarchies in natural capital.

Yes, natural capital influences both physical and mental health. Clean air, water, and food are essential for physical health, while access to green spaces reduces stress and improves mental well-being.

Recognition of mental health benefits has expanded the health value of ecosystems in urban planning and conservation policy.

Focusing mainly on economic values can lead to overexploitation of resources and neglect of cultural, spiritual, or intrinsic dimensions.

Key risks include:

Loss of biodiversity when habitats are valued only for extractive use.

Erosion of cultural identity tied to ecosystems.

Failure to recognise long-term environmental stability over short-term profit.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term natural capital and explain how it differs from natural income.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a correct definition of natural capital: stock of natural resources and ecosystems that provide goods and services.

1 mark for clear distinction of natural income: flow of goods and services (e.g., timber, fish, clean water) derived from natural capital.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how the values assigned to natural capital have changed over time, using two specific examples.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for recognition that values of natural capital are not static and shift with time.

Up to 2 marks for first example with explanation (e.g., coal valued highly during industrial revolution but declining due to environmental concerns).

Up to 2 marks for second example with explanation (e.g., lithium/cobalt gaining value in the 21st century due to demand for rechargeable batteries).

Responses must explicitly connect examples to changing societal, technological, or economic values to achieve full marks.