IB Syllabus focus:

‘Resource insecurity can degrade environments and fuel geopolitics (e.g., oil, battery minerals). Improve security by reducing demand, boosting supply, or shifting technologies in food, water, and energy.’

Globalisation shapes access to resources, linking markets, economies, and societies. Resource insecurity emerges when supply struggles to meet demand, creating environmental, social, and geopolitical consequences.

Globalisation and Resource Insecurity

Globalisation’s Influence

Globalisation describes the increasing interconnectedness of economies, societies, and cultures through trade, communication, and technology. This process has intensified the demand for energy, food, water, and raw materials worldwide.

While globalisation facilitates access to resources through trade networks, it also makes societies vulnerable to disruptions. Supply chains can be affected by political instability, natural disasters, or technological dependence.

Resource Insecurity

Resource insecurity occurs when the long-term availability of key resources cannot reliably meet demand. It is driven by several interconnected factors:

Economic growth leading to rising consumption.

Geopolitical tensions over resource-rich regions.

Environmental degradation reducing available supplies.

Technological change shifting demand toward new resources, such as lithium and cobalt.

Environmental Consequences of Insecurity

Resource insecurity directly degrades environments by intensifying extraction and overexploitation. Examples include:

Deforestation for timber and agricultural expansion.

Soil depletion through unsustainable farming practices.

Water scarcity intensified by climate change and industrial use.

Biodiversity loss from overfishing and mining operations.

Such environmental harm creates feedback loops, where degraded ecosystems further reduce resource availability.

Geopolitics and Conflict

Strategic Resources

Certain resources, such as oil, gas, lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements, carry strategic significance. Control over these can determine economic strength and political influence.

Tensions and Conflicts

Nations may compete for access to oil reserves, leading to conflicts in resource-rich regions.

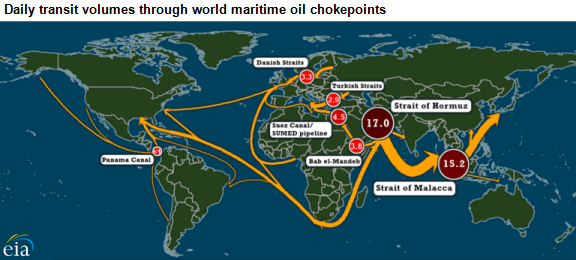

Global oil shipments are funneled through a handful of maritime chokepoints—such as the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca—where disruption can rapidly raise prices and destabilise supply. The map highlights volumes and locations of these strategic bottlenecks, illustrating how geography amplifies geopolitical risk in energy security. Source.

Supply chain disruptions in battery minerals can destabilise economies dependent on renewable energy technologies.

Water disputes between neighbouring countries, such as those sharing river basins, can escalate tensions.

Resource insecurity therefore acts as a driver of geopolitical instability, with global markets amplifying its impacts.

Improving Resource Security

Key Approaches

Improving security involves balancing consumption with sustainable supply. Three main strategies align with IB requirements:

Reducing demand

Promoting efficiency in energy and water use.

Encouraging reduced consumption through education and policy.

Supporting sustainable diets and local food systems.

Boosting supply

Diversifying sources of energy and food.

Investing in new water infrastructure, such as desalination.

Expanding renewable energy to reduce fossil fuel reliance.

Shifting technologies

Transitioning from fossil fuels to solar, wind, and hydroelectric power.

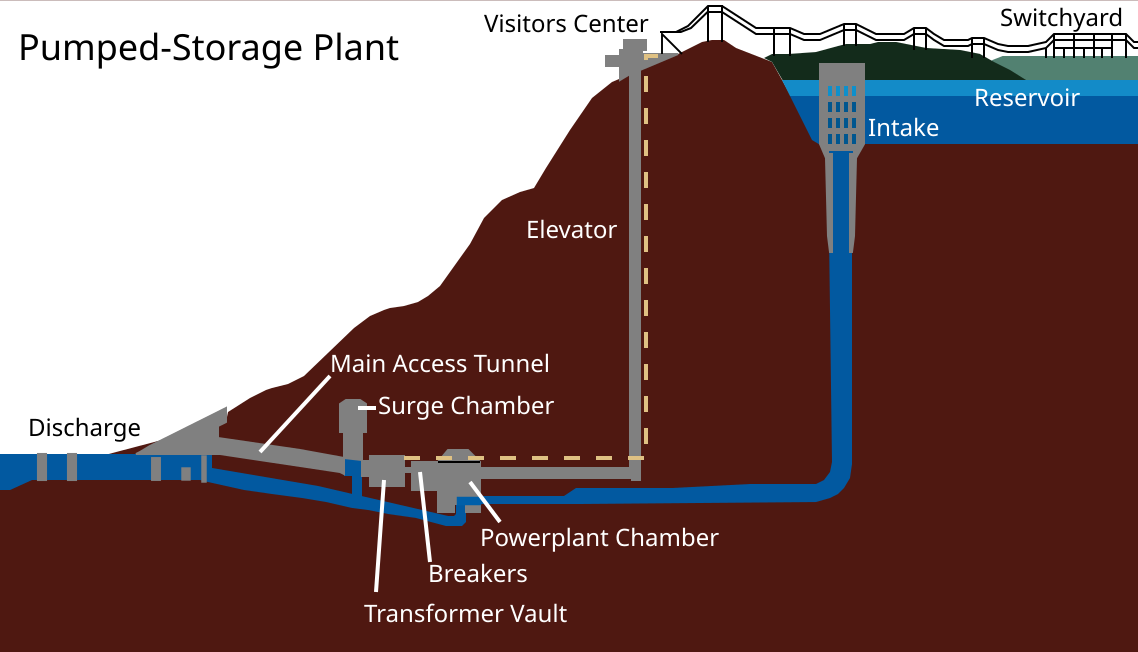

Developing storage systems to support intermittent renewables.

Pumped-storage hydropower stores surplus electricity by pumping water to an upper reservoir and later releases it through turbines to meet peak demand. The schematic clearly labels reservoirs, penstocks, turbines, and generators, illustrating how storage increases grid reliability and security. Source.

Advancing agricultural techniques such as precision farming.

International Cooperation

Resource security often requires international collaboration, as many challenges cross borders. Agreements on climate change, shared water use, and renewable energy research are vital to managing global insecurities.

Definitions

Globalisation: The process of increasing interconnectedness of societies, economies, and cultures through trade, communication, and technology.

Resource Insecurity: The risk that long-term availability of essential resources cannot reliably meet demand due to environmental, political, technological, or economic pressures.

Food, Water, and Energy Security

Food Security

Food security depends on stable production, affordable access, and sustainable farming systems. Globalisation spreads both agricultural technologies and vulnerabilities, such as reliance on global grain markets.

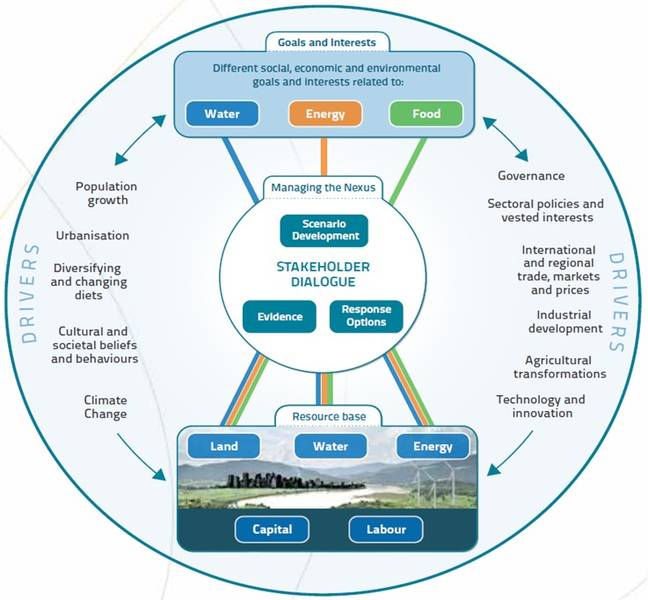

The water–energy–food nexus depicts reciprocal dependencies—energy is needed to pump and process water and produce food; agriculture depends on reliable water; and water systems require energy. Understanding these linkages helps explain how insecurity in one sector can cascade across others and informs integrated policy responses. Source.

Water Security

Water supplies are increasingly strained by population growth, climate change, and industrial demand. Shared rivers, like the Nile or Mekong, require transboundary agreements to reduce tensions.

Energy Security

Energy transitions complicate security. Fossil fuels are finite and geopolitically sensitive, while renewables rely on critical minerals, often controlled by few nations, adding new vulnerabilities.

Globalisation’s Double-Edged Nature

Advantages: Trade networks provide access to diverse resources, stimulate innovation, and allow cooperation in renewable energy and sustainable technologies.

Disadvantages: Dependence on global systems makes nations vulnerable to supply chain shocks, resource nationalism, and price fluctuations.

The challenge for societies lies in ensuring security while maintaining sustainability.

FAQ

Resource insecurity often drives human migration when local supplies of food, water, or energy become insufficient.

Communities facing prolonged drought, soil degradation, or depleted fisheries may relocate in search of sustainable livelihoods. This can create urban overcrowding, strain on infrastructure, and tension with host communities, particularly when resource competition intensifies in receiving regions.

Trade chokepoints are narrow transport routes critical for moving resources such as oil and gas.

Disruption at points like the Strait of Hormuz can rapidly destabilise global energy markets.

Even temporary blockages caused by accidents or conflict can lead to shortages, price spikes, and political instability.

Their importance makes them a frequent focus of geopolitical tension.

Battery minerals such as lithium and cobalt are geographically concentrated, with only a few countries dominating supply.

Globalisation increases dependence on these supply chains, making them vulnerable to:

Political instability in producer nations.

Labour exploitation and weak environmental regulation.

Export restrictions and trade disputes.

This creates systemic risk for renewable energy transitions worldwide.

Governments and corporations often prioritise short-term profits over long-term sustainability.

Overfishing for immediate economic gain can collapse fish stocks.

Expanding intensive farming for export may degrade soils and reduce future productivity.

Fossil fuel subsidies may discourage investment in renewables, locking societies into insecure energy systems.

Such decisions undermine resilience and deepen insecurity.

International cooperation is vital because many resources are transboundary.

Water-sharing agreements can prevent conflicts over rivers crossing national borders.

Global treaties on climate change encourage sustainable resource management.

Collaborative research and technology transfer improve efficiency and reduce dependency on unstable supplies.

Shared frameworks build trust and promote stability across resource systems.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term resource insecurity and explain one factor that can contribute to it.

Mark Scheme:

Definition of resource insecurity (1 mark):

The risk that long-term availability of essential resources cannot reliably meet demand due to environmental, political, technological, or economic pressures.

One valid factor explained (1 mark):

Examples: economic growth, geopolitical tensions, environmental degradation, technological change.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how globalisation can both increase and decrease resource security, using examples from food, water, or energy resources.

Mark Scheme:

Identification of how globalisation can increase resource security (1–2 marks):

Examples: improved trade networks, access to diverse resources, technology transfer, international cooperation.

Identification of how globalisation can decrease resource security (1–2 marks):

Examples: dependence on global supply chains, vulnerability to geopolitical tensions, unequal access, environmental pressures.

Use of at least one specific example related to food, water, or energy (1 mark).

Maximum 5 marks available.