IB Syllabus focus:

‘Urbanization shifts land use and people to cities. Migration is mainly internal, driven by push–pull and voluntary or forced factors; consider parallel trends like deurbanization.’

Urbanization is a central process shaping human societies, where the movement of people from rural to urban areas leads to rapid social, economic, and environmental transformations worldwide.

Understanding Urbanization

Urbanization refers to the increasing proportion of a population living in towns and cities rather than in rural areas. It involves both land-use changes (conversion of farmland or natural environments into built-up areas) and population movement, usually in the form of rural–urban migration. This migration is often internal (within a country) and contributes to urban growth alongside natural population increase.

Rural–Urban Migration Defined

Rural–urban migration: The movement of people from the countryside to towns and cities, usually in search of better opportunities or living conditions.

Rural–urban migration is a key driver of urbanization, though the process also includes natural growth from higher urban birth rates compared with death rates in some regions.

Urbanization shifts land use and people to cities.

This world map shows the proportion of each country’s population living in urban areas, illustrating how urbanization varies globally and has increased over time. It complements the discussion of population shifts to cities by providing a comparative, country-level view. The underlying data follow UN and World Bank definitions of ‘urban’. Source.

Push and Pull Factors in Migration

Migration decisions are shaped by push and pull factors:

Push factors (reasons people leave rural areas):

Poverty and limited economic opportunities

Land degradation and lack of arable land

Natural hazards such as droughts or floods

Poor access to healthcare and education

Political instability or conflict

Pull factors (reasons people move to urban areas):

Availability of jobs and higher wages

Better healthcare and education services

Improved infrastructure such as electricity, transport, and water supply

Greater social and cultural opportunities

Perceived higher standard of living

This balance of pressures and attractions explains why cities continue to grow even when urban challenges exist.

Voluntary and Forced Migration

Migration to urban areas can be either voluntary or forced:

Voluntary migration occurs when individuals or families choose to relocate, often for employment, education, or improved quality of life.

Forced migration happens when people are compelled to move, such as through war, natural disasters, eviction, or large-scale development projects.

Forced migration: The movement of people under coercion or duress, often due to conflict, natural hazards, or government action.

The distinction matters because voluntary migration reflects personal agency, while forced migration highlights vulnerability and external pressures.

Trends in Urbanization

Urbanization is not uniform across the globe. In more economically developed countries (MEDCs), the majority of the population is already urban, and urban growth rates have slowed. In contrast, less economically developed countries (LEDCs) often experience rapid urban growth due to both higher fertility rates and large-scale migration.

Deurbanization

While the dominant trend globally is urban growth, some countries experience deurbanization — the movement of people away from cities back into rural or semi-rural areas.

Deurbanization: The process in which people migrate from cities to smaller towns or rural areas, often to avoid congestion, pollution, or high living costs.

This trend is observed particularly in parts of North America and Europe, where suburban and exurban growth allows people to live outside dense city centres while still maintaining urban connections.

Migration is mainly internal, driven by push–pull and voluntary or forced factors; consider parallel trends like deurbanization.

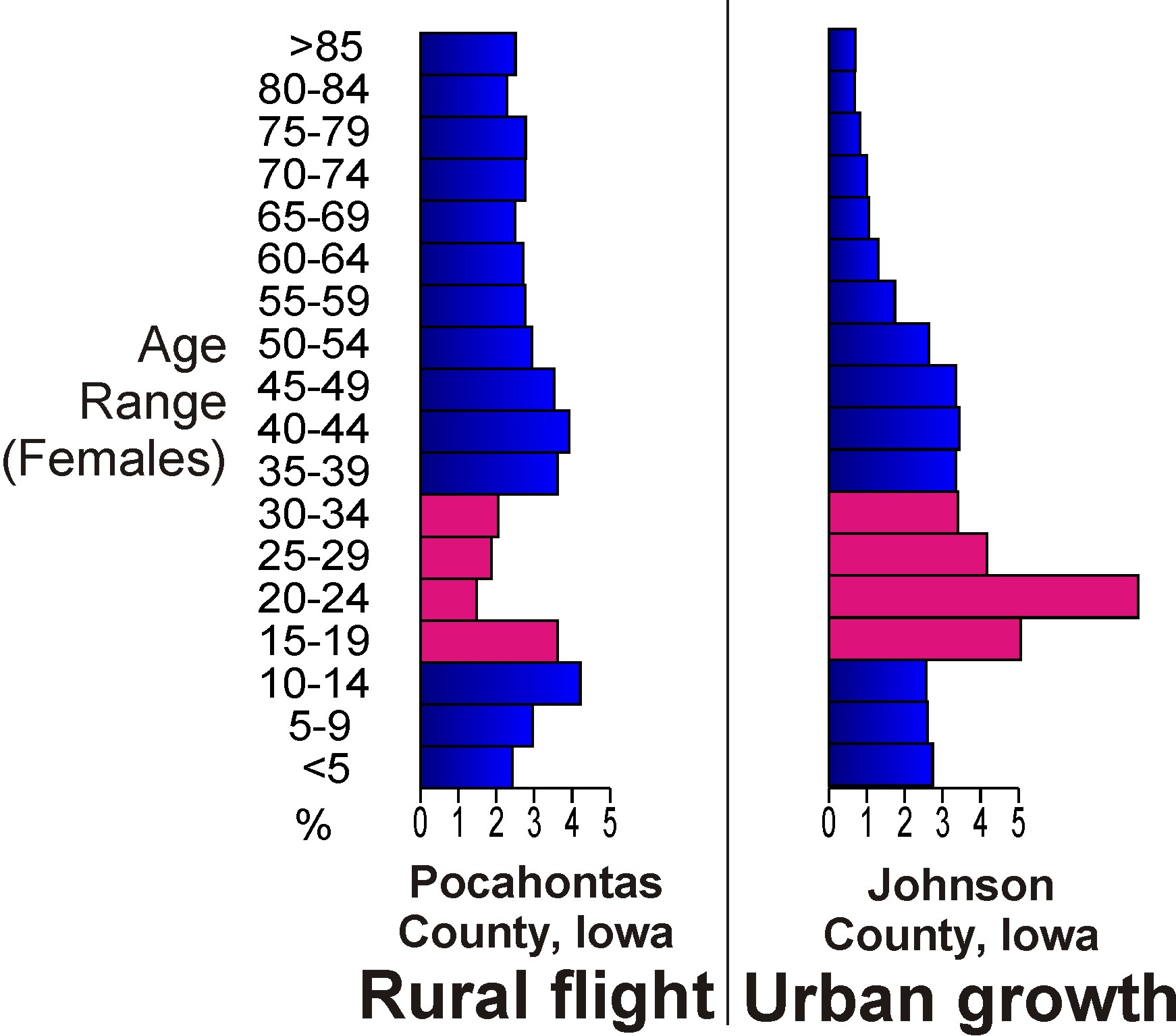

This graphic compares female age distributions in a rural county and a nearby urban county, with the pronounced deficit of young adults in the rural profile indicating rural-to-urban migration. It provides a concrete visual for age-selective internal migration discussed in the notes. This is a U.S. example, but the pattern is common in many countries. Source.

Social and Economic Consequences

The effects of rural–urban migration are profound:

For rural areas:

Loss of young, working-age populations

Reduced agricultural productivity

Ageing population left behind

Remittances (money sent home) may help rural families financially

For urban areas:

Rapid expansion of informal settlements and slums

Increased demand for housing, jobs, and services

Strain on infrastructure (transport, sanitation, healthcare)

Greater social diversity and cultural exchange

These consequences highlight why urbanization is both a challenge and an opportunity for sustainable development.

Environmental Impacts of Migration and Urbanization

Urban growth linked to migration has significant environmental outcomes:

Land-use change: farmland and natural habitats converted into built environments

Pollution: increased waste, air pollution, and water contamination

Urban sprawl: expansion of cities into surrounding countryside

Pressure on resources: rising demand for water, energy, and food supplies

These impacts make urban planning essential for managing sustainable growth.

Migration Dynamics in Context

Urbanization cannot be understood without recognising the wider context:

Economic development drives rural–urban migration by creating jobs in cities.

Government policies may encourage or restrict migration. For example, rural development schemes may reduce out-migration, while urban investment draws people in.

Globalisation increases urban growth as cities become centres of trade, finance, and communication.

Cultural changes influence migration, as urban areas often provide greater gender equality and social freedoms.

Internal vs International Migration

While the syllabus emphasises internal migration, it is important to note that international migration also contributes to urban growth. Major world cities attract migrants from abroad, creating diverse populations. However, internal rural–urban migration remains the dominant factor shaping national patterns of urbanisation.

Key Takeaways for Students

Urbanization is the shift of people and land use towards cities.

Rural–urban migration is mainly internal and shaped by push and pull factors.

Migration can be voluntary or forced, with different social implications.

Deurbanization exists alongside urbanisation, particularly in MEDCs.

Consequences affect both rural areas (loss of population) and urban areas (pressure on infrastructure).

Urbanisation has major environmental impacts requiring sustainable planning and policy responses.

FAQ

Remittances are funds sent home by migrants working in urban areas. These can provide essential financial support to rural households, helping with education, healthcare, or farming costs.

They may also reduce poverty in rural communities, but reliance on remittances can discourage local economic development and make families dependent on external income.

Rural–urban migration is often age-selective, with young adults being the most likely to migrate.

Young people move for education, job opportunities, or social mobility.

This leads to an ageing population in rural areas.

Cities benefit from a growing workforce but face pressure to provide services for younger age groups.

Rapid migration into cities often exceeds the capacity of urban infrastructure. As a result, many migrants cannot afford formal housing.

Informal settlements, or slums, develop on city edges or unused land. These provide shelter but often lack clean water, sanitation, and secure tenure, creating social and environmental challenges.

In MEDCs, rural–urban migration has slowed because urbanisation levels are already high. Deurbanisation may occur as people seek better quality of life outside congested cities.

In LEDCs, migration remains rapid, driven by higher fertility rates, poverty, and strong push–pull factors. This often leads to fast urban growth and expansion of informal settlements.

Sudden influxes of migrants into cities can strain natural resources and worsen environmental degradation.

Deforestation may occur as land is cleared for housing.

Water supplies can be overused or polluted.

Air quality may decline due to increased transport and industry.

Waste management systems often fail, leading to unsanitary conditions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define rural–urban migration and outline one push factor that drives this process.

Mark scheme:

Definition of rural–urban migration: movement of people from rural areas to towns/cities for better opportunities (1 mark)

Correct example of a push factor, e.g. poverty, lack of jobs, land degradation, natural hazards, or limited access to services (1 mark)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how both voluntary and forced migration contribute to rural–urban migration, using examples to support your answer.

Mark scheme:

Identification of voluntary migration as a choice to move for reasons such as employment, education, or higher living standards (1 mark)

Explanation of how voluntary migration contributes to urbanisation through increasing city populations (1 mark)

Identification of forced migration as compelled movement due to conflict, natural hazards, eviction, or other pressures (1 mark)

Explanation of how forced migration leads to urban growth, often creating sudden population increases or pressures on resources (1 mark)

Use of at least one relevant example for either voluntary or forced migration (1 mark)