IB Syllabus focus:

‘Movement from dense centres to lower-density edges creates sprawl, increasing land consumption and infrastructure needs.’

Suburbanisation and urban sprawl describe population movement and land-use changes as people shift from dense urban cores to expanding edges, increasing land consumption and infrastructure requirements.

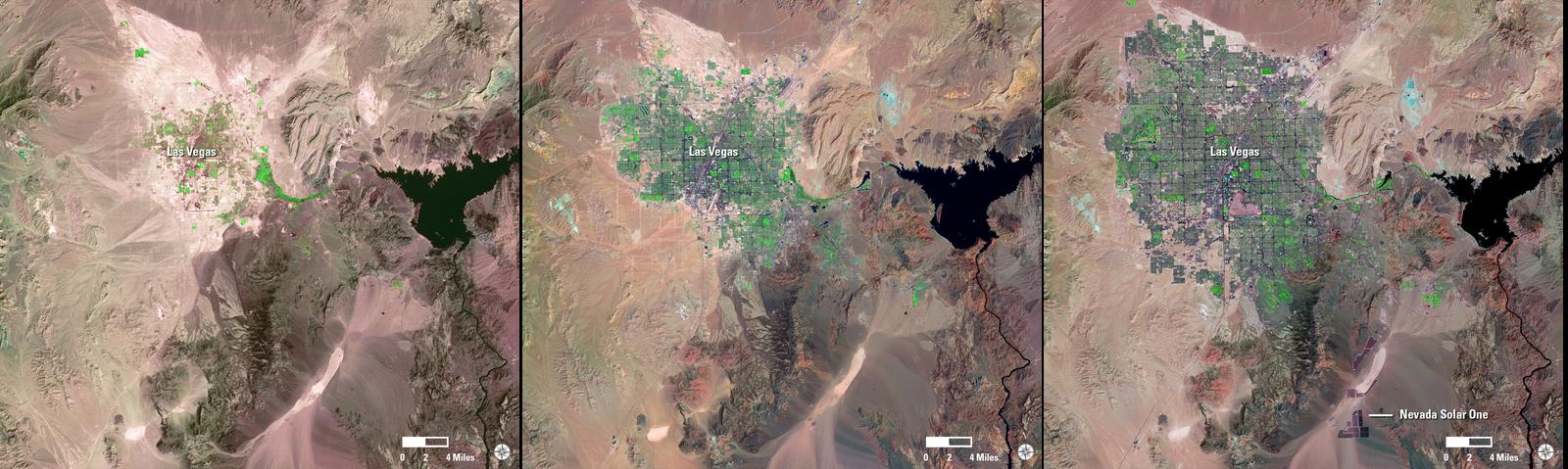

Landsat imagery of Las Vegas across decades reveals radial expansion from the core into the desert, a textbook pattern of urban sprawl. The growing footprint visualises how low-density edge development consumes land and necessitates longer networks of roads, water, and power. Source.

Understanding Suburbanisation

Suburbanisation occurs when people and businesses move away from the urban core to the urban periphery. This process is driven by social, economic, and environmental factors that make suburban areas more attractive for settlement.

Key Drivers of Suburbanisation

Economic factors: lower land and housing costs compared to city centres.

Transport improvements: development of railways, motorways, and public transit allowing commuting.

Quality of life: preference for less congested, greener residential areas.

Government policies: incentives for housing and development on the outskirts of cities.

Urban Sprawl

Urban sprawl is the uncontrolled, low-density expansion of urban areas into previously rural land. Unlike planned suburban growth, sprawl is typically dispersed and inefficient, leading to sustainability challenges.

Oblique aerial photo showing extensive low-density subdivisions with wide separations between residential blocks and arterial roads. The pattern exemplifies car-dependent sprawl that increases per-capita infrastructure length and land take. Source.

Urban Sprawl: The uncontrolled spread of urban development into rural areas, usually characterised by low-density housing, heavy reliance on cars, and fragmented land use.

Characteristics of Urban Sprawl

Low-density housing (detached homes with large plots).

Car dependency due to limited public transport.

Loss of farmland and green spaces as land is consumed.

Zoning separation of housing, industry, and commercial areas, making mixed-use development rare.

Environmental Consequences

Urban sprawl impacts natural systems and contributes to unsustainable land use.

Major Environmental Impacts

Loss of agricultural land: fertile farmland is converted into residential or commercial zones.

Biodiversity loss: habitats are fragmented, reducing species survival.

Increased energy use: reliance on cars boosts fossil fuel consumption.

Air pollution: car dependency raises emissions of NOx, CO, and particulates.

Water quality reduction: more impermeable surfaces increase runoff and reduce groundwater recharge.

Social and Economic Effects

Suburbanisation and urban sprawl reshape communities, often with mixed consequences.

Positive Impacts

Affordable housing opportunities for families.

Reduced congestion in city centres.

Perceived safety and better quality of life in suburban environments.

Negative Impacts

Social segregation as wealthier residents move outward, leaving vulnerable populations in the city.

Commuter stress due to long travel times.

Strain on public services as infrastructure must stretch further.

Infrastructure Demands

Sprawl increases pressure on existing urban systems. Cities must extend services and utilities over larger areas, which is costly and resource-intensive.

Common Infrastructure Expansions

Transport networks (roads, highways, and rail lines).

Utilities (electricity, water supply, sewage treatment).

Public services (schools, hospitals, emergency services).

Sustainable Approaches to Managing Sprawl

Although sprawl often appears uncontrolled, planning can reduce its negative effects.

Strategies for Sustainability

Compact city development: focusing on higher-density housing and mixed-use neighbourhoods.

Transit-oriented development (TOD): prioritising public transport and reducing car reliance.

Green belts: legally protected areas around cities to restrict outward growth.

Smart growth policies: integrating housing, jobs, and services in walkable communities.

Case Study Elements

In IB ESS, understanding real-world patterns enhances comprehension. Suburbanisation is common in rapidly growing cities such as Los Angeles and Beijing, where population pressures and infrastructure expansion have led to widespread sprawl, loss of farmland, and worsening pollution. European cities such as London have attempted to counter sprawl with green belt policies.

Links to Population Dynamics

Suburbanisation connects directly to population growth trends:

High birth rates and migration increase pressure for housing.

Rising incomes allow families to seek larger homes outside the city.

Age–sex structures influence suburban demand, as younger families dominate suburban growth.

Urban Planning Considerations

Suburbanisation and urban sprawl highlight the importance of planning for sustainability. Without structured land-use policy, sprawl leads to higher carbon emissions, infrastructure inefficiency, and ecological loss. Sustainable urban planning aims to balance growth with environmental protection and quality of life.

FAQ

Planned suburbanisation involves controlled expansion with designated zoning, integrated transport systems, and services designed to support residents efficiently.

Unplanned urban sprawl, by contrast, develops without strategic planning, often leading to fragmented land use, inefficient transport, and a lack of accessible services such as schools or healthcare.

Car dependency allows people to live further from city centres because commuting is possible by private vehicle.

This encourages developers to build low-density housing estates spread across wider areas. Over time, this reliance on cars increases fuel consumption, air pollution, and traffic congestion, reinforcing sprawl patterns.

Governments face competing pressures between economic growth, housing demand, and environmental protection.

Developers often push for cheaper peripheral land, while politicians prioritise affordable housing. Weak enforcement of zoning laws, fragmented jurisdictions, and limited funding for public transport make effective sprawl control difficult.

Rural communities often experience land-use changes as farmland is sold for development.

This can reduce local agricultural production, increase property prices beyond the reach of long-term residents, and alter traditional community structures.

At the same time, it may bring improved infrastructure and job opportunities linked to construction and service industries.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) allow planners to track land-use changes and predict future sprawl patterns.

Technologies supporting smart growth include:

Energy-efficient housing design

Real-time traffic monitoring to reduce congestion

Digital public consultation platforms to include community voices

These innovations help ensure suburban growth is more sustainable and less environmentally damaging.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define the term urban sprawl and identify one environmental impact associated with it.

Mark Scheme:

Definition of urban sprawl (1 mark): e.g. uncontrolled/low-density spread of urban areas into rural land.

Identification of one environmental impact (1 mark): e.g. loss of farmland, habitat destruction, increased air pollution, or higher car dependency.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain two social or economic consequences of suburbanisation and urban sprawl, and discuss how these may create challenges for sustainable urban planning.

Mark Scheme:

Explanation of first consequence (up to 2 marks): e.g. social segregation, longer commuting times, strain on city services, or affordable housing availability.

Explanation of second consequence (up to 2 marks): as above, separate from first.

Link to challenges for sustainable urban planning (1 mark): e.g. higher infrastructure costs, increased carbon emissions, or difficulty in integrating efficient public transport.