OCR Specification focus:

‘Recognise limitations in experimental procedures and discuss their impact on the validity of conclusions.’

Introduction

Understanding procedural limitations is essential in A-Level Chemistry, as it allows students to critically evaluate how experimental design, equipment, and human factors influence the validity of results and conclusions.

Recognising Procedural Limitations

Procedural limitations are aspects of an experiment’s design or execution that can affect the accuracy, precision, or validity of the results. Recognising these limitations allows chemists to assess how reliable their conclusions are and to identify ways to improve the experiment.

The Role of Validity in Experimental Chemistry

Validity refers to how well an experiment measures what it is intended to measure. If procedural flaws exist, the validity of the data and subsequent conclusions may be compromised.

Types of validity to consider:

Internal validity: Whether the observed effects are genuinely due to the manipulated variable rather than uncontrolled factors.

External validity: Whether the results can be generalised to other conditions, systems, or real-world applications.

Common Procedural Limitations

Several recurring limitations can affect the quality of experimental results. These can arise from apparatus, method design, human error, or environmental factors.

1. Equipment and Apparatus

Instrument calibration: Equipment such as balances and thermometers may be uncalibrated or drift over time.

Resolution limits: Instruments can only measure to a certain degree of precision, affecting the number of significant figures used.

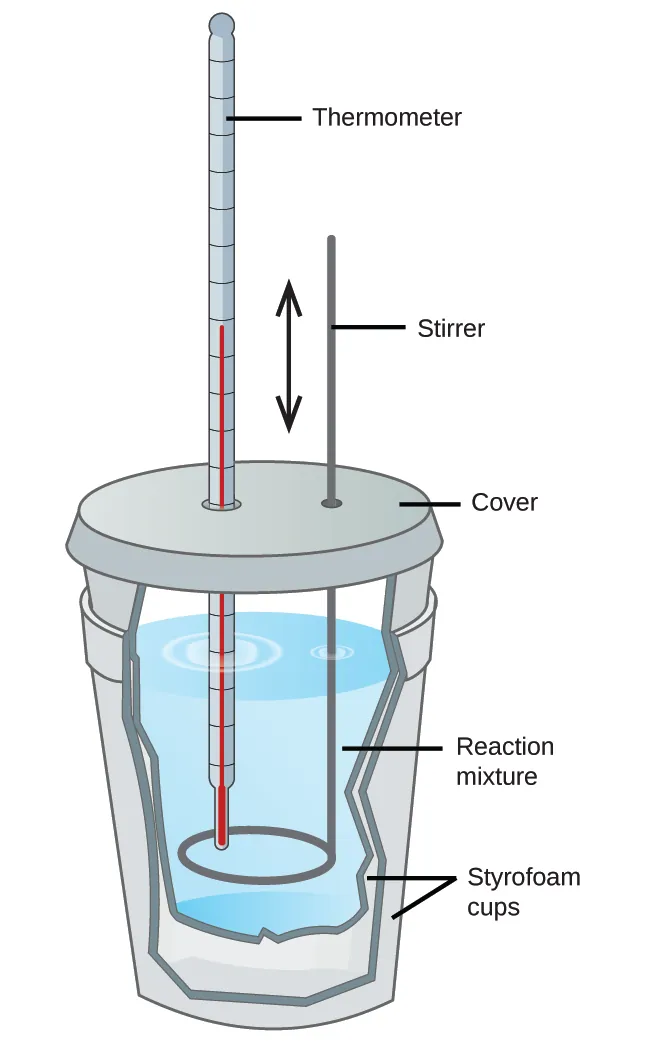

Reaction vessel choice: Some reactions require specific containers to prevent heat loss or contamination (e.g. using polystyrene cups for calorimetry).

Material limitations: Glassware may absorb chemicals or allow heat transfer, influencing measured values.

2. Measurement and Technique

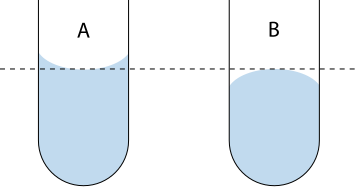

Parallax error: Occurs when readings on scales are taken from an angle rather than directly in line.

A schematic of proper meniscus reading at eye level, illustrating how viewing from above or below introduces parallax error. The diagram reinforces that volume must be read at the bottom of the meniscus with the sight line perpendicular to the scale. This aligns with good volumetric technique required for reliable measurements. Source

Inconsistent timing: Human reaction time when using stopwatches introduces uncertainty.

Incomplete reactions: Some reactions may not reach completion, particularly if equilibrium is involved.

Temperature control: Fluctuations in ambient temperature may alter reaction rates or solubility.

3. Sample and Reagent Considerations

Purity of reagents: Impurities can affect reaction rates and yields.

Sample size: Too small a sample can increase relative error; too large may be impractical or unsafe.

Homogeneity: Inconsistent mixing or sampling leads to uneven distribution of reactants.

4. Environmental Factors

Humidity and air pressure: These can affect mass readings and gas volumes.

Temperature drift: Especially relevant in thermodynamic or kinetic experiments.

Light exposure: Photosensitive reactions may behave differently in varying light conditions.

Procedural Limitation: Any flaw or restriction in the design, materials, equipment, or technique of an experiment that can reduce the accuracy, precision, or validity of results.

Linking Procedural Limitations to Reliability and Accuracy

Reliability depends on whether the experiment can produce consistent results when repeated under identical conditions. Procedural limitations, such as inconsistent measuring techniques or variable environmental conditions, reduce reliability.

Accuracy, on the other hand, describes how close results are to the true or accepted value. Procedural flaws, such as systematic errors from faulty apparatus, directly impact accuracy.

Both reliability and accuracy are influenced by how well procedural limitations are identified and mitigated.

Identifying Limitations During Experimentation

When performing or evaluating an experiment, students should actively identify where procedural errors could arise.

Steps to identify limitations:

Review the experimental aim and ensure the method truly tests that aim.

Check for consistency in measurement methods between trials.

Evaluate whether the apparatus chosen suits the scale and precision required.

Consider external variables that may affect results, such as ambient temperature or humidity.

Reflect on human involvement, such as judgement-based endpoints (e.g. colour change titrations).

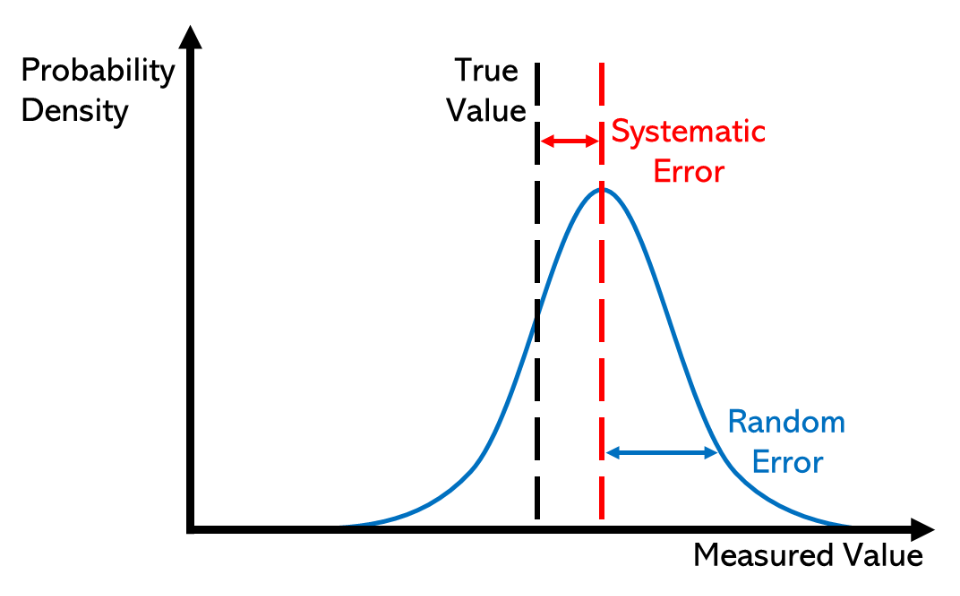

Systematic Error: An error that consistently skews results in one direction due to a flaw in procedure or equipment, affecting accuracy.

Systematic errors often arise from procedural issues like calibration errors, incorrect reagent concentrations, or heat losses. Unlike random errors, these cannot be reduced by repetition alone.

Probability density curves highlighting random error (spread around the mean) versus systematic error (uniform offset from the true value). The figure clarifies why repeating trials alone does not remove bias introduced by a flawed method or apparatus. Use it to connect procedural flaws to accuracy and reliability discussions. Source

Evaluating the Impact of Limitations

Once limitations are recognised, their impact on validity should be assessed. This means judging whether the limitation changes the interpretation of the results.

Example impacts include:

A significant systematic error could invalidate calculated constants or reaction rates.

Incomplete reactions could result in underestimation of yields.

Poorly controlled variables could make cause-and-effect relationships unclear.

Students should state whether the limitation causes minor deviations (acceptable uncertainty) or fundamentally undermines the reliability of conclusions.

Strategies to Mitigate Procedural Limitations

While recognising limitations is key to evaluation, suggesting improvements demonstrates understanding.

Ways to reduce procedural limitations include:

Use of calibrated equipment to ensure consistent accuracy.

Improved temperature control through thermostatic baths or insulated containers.

Repeating experiments and calculating mean values to increase reliability.

Using digital sensors instead of manual readings to reduce human error.

Standardising reagent concentrations and volumes across trials.

Implementing control experiments to isolate the effect of specific variables.

These refinements enhance data quality and strengthen the validity of conclusions drawn.

Diagram of a simple coffee-cup calorimeter with two nested polystyrene cups, lid, thermometer, and stirrer. It visually connects insulation choices to reduced systematic heat loss, which otherwise biases measured enthalpy changes. Note: the page also shows more advanced calorimeters; only the Figure 5.12 student model is required at this level. Source

Control Variable: A variable kept constant during an experiment to ensure that changes in the dependent variable are due only to the manipulation of the independent variable.

Maintaining control variables consistently helps minimise procedural limitations, as uncontrolled factors are a major cause of invalid results.

Evaluating Procedures in the Context of Aims

A critical part of the OCR specification is assessing whether the chosen method aligns with the experimental aims. Even a technically sound procedure may have limitations if it does not directly address the research question. For instance, a titration method might accurately determine concentration but fail to capture reaction kinetics.

Therefore, evaluation must link the method, data, and aim coherently. Students should ask:

Does the procedure directly test the intended hypothesis?

Were measurements sufficiently precise and accurate for valid conclusions?

Were all significant sources of procedural limitation acknowledged?

The Examiner’s Expectation

In OCR A-Level Chemistry written examinations, students must:

Identify specific procedural limitations in given methods.

Explain why these limitations occur (e.g. apparatus design, technique used).

Discuss their impact on validity, distinguishing between random and systematic effects.

Suggest practical improvements to address the identified weaknesses.

Developing this evaluative skill shows both chemical understanding and experimental literacy, aligning directly with the specification’s requirement to recognise and discuss procedural limitations and their effects on validity.

FAQ

Procedural errors arise from flaws in the design, setup, or method of an experiment, such as poor temperature control or using unsuitable apparatus. Human error, on the other hand, is due to mistakes made by the experimenter, such as misreading a scale or spilling a reagent.

Procedural errors can often be minimised by refining the method, while human errors are reduced through careful practice, attention, and repetition.

Random errors cause unpredictable fluctuations in measurements and can be reduced by repeating the experiment and calculating a mean.

Systematic errors consistently skew results in one direction due to faulty equipment or flawed design.

A good indicator of a systematic error is when repeated measurements all deviate from the true value by a similar amount.

Recognising procedural limitations shows that a student understands how method design affects data quality and validity. Examiners assess this skill to gauge analytical thinking.

Students should be able to:

Identify specific weaknesses (e.g. heat loss, calibration drift)

Explain how these affect results

Suggest realistic improvements that enhance reliability or accuracy

This demonstrates higher-level evaluation rather than simple recall.

Yes. If control variables are not maintained consistently or are poorly chosen, they become a procedural limitation. For example:

In a rate experiment, failing to control temperature changes affects reaction speed.

In a titration, varying concentration of one reagent introduces inconsistency.

Procedural rigour requires identifying which variables need to remain constant and monitoring them throughout.

Apparatus precision determines how finely a measurement can be made. Low-precision equipment increases measurement uncertainty and limits result reliability.

For instance, using a 50 cm³ measuring cylinder instead of a burette produces greater uncertainty in volume readings. Choosing apparatus that matches the precision needed for the experimental aim is key to minimising procedural limitations.

Practice Questions

A student measures the volume of liquid in a burette but records it while looking down from above the meniscus. Explain why this reading may be inaccurate and identify the type of procedural limitation involved.

(2 marks)

1 mark for stating that reading from above the meniscus causes an incorrect volume to be recorded (reading too high or too low).

1 mark for identifying the procedural limitation as parallax error due to incorrect eye alignment.

A student conducts an experiment to determine the enthalpy change of neutralisation using a simple polystyrene cup calorimeter. The calculated enthalpy change is significantly lower than the literature value.

(a) Suggest two procedural limitations that could have caused this discrepancy. (2 marks)

(b) Explain how each limitation affects the accuracy of the result. (2 marks)

(c) Suggest one improvement to the procedure that would reduce these limitations. (1 mark)

(5 marks)

(a) 1 mark for identifying each valid limitation, such as:

Heat loss to the surroundings.

Incomplete insulation or lack of lid.

Inaccurate temperature readings due to delayed thermometer response.

(b) 1 mark for explaining each effect:

Heat loss results in a smaller temperature rise, giving a lower calculated enthalpy change.

Poor insulation allows energy exchange with the environment, reducing measured temperature change.

(c) 1 mark for suggesting an appropriate improvement:

Use a lid, improved insulation, or a more precise digital thermometer to reduce heat loss and improve accuracy.