OCR Specification focus:

‘Evaluate results and draw conclusions supported by evidence and reasoning, considering the quality of the data.’

Introduction

Evaluating results and conclusions is a key part of scientific investigation, ensuring that findings are supported by valid evidence and logical reasoning while considering data quality and limitations.

Understanding Evaluation in Experimental Chemistry

Evaluation in chemistry involves critically examining the results and conclusions drawn from experiments. It requires assessing how well the evidence supports the claims made and identifying any sources of uncertainty or error that may affect reliability.

A strong evaluation demonstrates scientific reasoning, linking data analysis, measurement quality, and experimental validity to conclusions. It ensures that results are not just accurate but also trustworthy and scientifically sound.

Assessing the Quality of Data

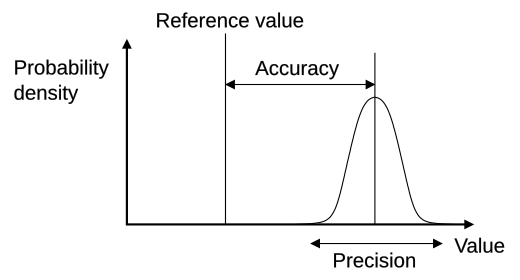

Accuracy and Precision

When evaluating results, students must distinguish between accuracy and precision.

A labelled target diagram contrasting high/low accuracy with high/low precision. This helps evaluate whether results are close to the true value (accuracy) and/or closely grouped (precision). Use it to justify conclusions about data quality. Source

Accuracy: The closeness of a measured value to the true or accepted value.

Precision: The degree to which repeated measurements under unchanged conditions show the same results.

Accurate results depend on correct calibration and minimal systematic error, while precise data indicates consistent experimental technique. Both qualities contribute to the reliability of conclusions.

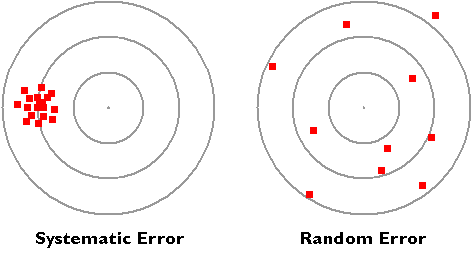

A diagram contrasting a systematic offset (bias) with a randomly distributed measurement spread. It clarifies how bias shifts results away from the true value while random error widens the spread. This underpins evaluation of reliability and validity. Source

Reliability of Data

Reliability refers to the extent to which experimental results can be trusted and repeated. High reliability requires:

Consistent procedures and controlled variables

Repetition of trials to check for anomalies

Use of appropriately sensitive and calibrated equipment

Agreement with secondary data or literature values

Interpreting and Supporting Conclusions

Linking Evidence to Conclusions

A scientific conclusion must be based on evidence, not assumptions. The reasoning should:

Directly reference experimental data

Use quantitative comparisons (e.g., differences between expected and obtained values)

Explain trends using relevant chemical principles

A conclusion stating that a reaction rate increases with temperature, for example, must refer to specific measured data supporting this trend and link it to the collision theory of particles.

Consistency with Theoretical Models

Conclusions should be evaluated against established chemical theories. If results deviate from theoretical expectations, this does not necessarily mean the theory is incorrect; instead, it prompts analysis of:

Possible procedural errors

Limitations in data precision

Unaccounted external factors (e.g., heat loss, impurities)

Considering the Quality of the Experimental Design

Control of Variables

An effective evaluation considers whether all controlled variables remained constant throughout the experiment. Uncontrolled changes, such as fluctuations in room temperature or inconsistent reagent concentration, can lead to invalid results.

Appropriateness of Apparatus

The suitability of chosen apparatus influences data quality. When evaluating results, ask:

Was the equipment sensitive enough for the required measurements?

Was calibration performed correctly?

Were measurement scales appropriate to reduce percentage error?

Percentage Error (%) = (|Measured – True Value| ÷ True Value) × 100

Measured = Recorded experimental value

True Value = Accepted or theoretical value

Evaluating results often involves comparing these errors to determine whether the deviation is within an acceptable range.

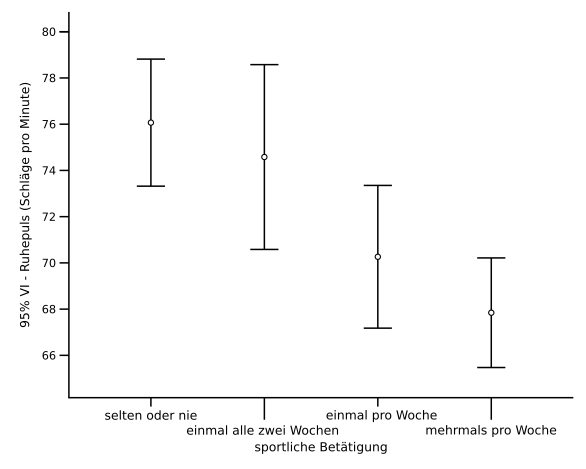

Recognising Uncertainty and Limitations

Measurement Uncertainty

All measurements include uncertainty, which represents the range within which the true value is expected to lie.

A bar chart with 95% confidence interval error bars. It illustrates how uncertainty is shown graphically and how interval width relates to precision. This supports evaluation of whether differences are meaningful. Source

When evaluating results:

Express uncertainties clearly with each measurement (e.g., ±0.1 cm³).

Propagate uncertainties through calculations to estimate total error.

Discuss how uncertainties may influence final conclusions.

Limitations of Experimental Method

Every method has inherent limitations. Examples include:

Incomplete reactions affecting yield measurements

Heat loss in calorimetry affecting enthalpy values

Evaporation losses during titration

Acknowledging these limitations demonstrates scientific awareness and transparency.

Evaluating the Strength of Conclusions

Validity of Conclusions

A valid conclusion accurately reflects the evidence and does not overstate results. To assess validity:

Check that data trends are consistent with the conclusion.

Ensure that no results are ignored without reason.

Avoid generalisations beyond the scope of the experiment.

Comparing with Literature or Theoretical Values

When possible, compare experimental outcomes with literature values or theoretical predictions. Agreement supports validity, while discrepancies should be analysed to identify potential causes.

Statistical Considerations

Though not always required, evaluating data using basic statistical tools (e.g., mean, range, percentage deviation) can enhance the credibility of conclusions. High variability may indicate poor precision and reduce confidence in conclusions.

Reflecting on the Evidence and Reasoning

Evidence-Based Reasoning

Chemistry evaluation requires students to justify conclusions with logical reasoning:

Link observed patterns to chemical theory (e.g., redox potential, reaction kinetics).

Explain discrepancies scientifically, not anecdotally.

Use data to support every claim made in the conclusion.

Evaluating Anomalies

Anomalous results are those that deviate from expected trends. Evaluation should:

Identify anomalies clearly using data comparisons.

Suggest reasonable scientific explanations (e.g., contamination, instrumental error).

Indicate whether anomalies significantly affect the final conclusion.

Improving Reliability and Validity

An essential aspect of evaluation is suggesting improvements to enhance future investigations. These may include:

Using apparatus with smaller uncertainties

Increasing the number of repeats

Maintaining stricter control of environmental conditions

Refining data collection methods for greater consistency

Such suggestions demonstrate understanding of how experimental reliability and data quality influence conclusions.

Linking Evaluation to Broader Practical Skills

Evaluating results is not a separate step but part of a continuous process of scientific enquiry. It integrates observation, data analysis, and critical thinking to produce well-founded conclusions. Through this process, chemists ensure that their findings are both scientifically valid and reproducible, aligning with the core OCR A-Level Chemistry practical skills assessment.

FAQ

Reliability refers to the consistency of results — whether repeating the experiment produces similar outcomes. It’s assessed through repeat trials and concordant data.

Validity, however, concerns whether the results and conclusions are genuinely measuring what they are intended to measure. Even reliable data can be invalid if key variables are uncontrolled or the method is flawed.

Reliable results are not automatically valid, but valid conclusions must be based on reliable data.

Bias occurs when results are consistently shifted in one direction due to systematic errors or investigator influence.

Common sources of bias include:

Poorly calibrated instruments

Selective use of data (ignoring anomalies)

Human reading errors from parallax

To minimise bias:

Use blind or automated measurements

Cross-check calibration with standards

Evaluate data using objective criteria

Bias weakens the credibility of conclusions and should always be addressed in evaluation.

Repeatability demonstrates that results are consistent under identical conditions. If repeated measurements yield similar values, it strengthens confidence in data quality.

When evaluating results, repeatability helps identify:

Random errors — shown by inconsistent data

Procedural consistency — confirmed by small variation

High repeatability indicates the experiment is well controlled and the measurements are precise, supporting stronger conclusions.

A well-justified conclusion should:

Directly reference experimental data (quantitative or qualitative)

Use relevant chemical theory to explain observations

Account for any anomalies or uncertainties

Compare results to accepted or literature values, where available

Avoid speculative statements. Every point made in the conclusion should be supported by evidence and reasoning, not assumption.

Clear presentation helps identify trends, anomalies, and data reliability. Poorly structured data can obscure meaningful patterns.

Good practice includes:

Using consistent units and significant figures

Including error bars to show uncertainty

Labelling axes clearly when plotting graphs

Arranging data logically in tables

Well-presented data allow for accurate interpretation and more confident evaluation of conclusions.

Practice Questions

A student measures the temperature change in a neutralisation reaction three times and records the following results:

24.5 °C, 25.0 °C, 24.8 °C.

(a) Comment on the precision of these results.

(b) Suggest one possible reason why these results might not be accurate.

(2 marks)

(a)

Results are precise because they are close together/consistent (1 mark).

(b)

Not accurate because of systematic error, e.g. thermometer not calibrated correctly, heat lost to surroundings, or incomplete mixing (1 mark).

Total: 2 marks

A student carries out a titration to determine the concentration of an acid. The student obtains a mean titre of 25.30 cm³. The accepted value is 25.00 cm³.

(a) Calculate the percentage error in the student’s result.

(b) Evaluate the reliability and validity of the student’s conclusion that their acid concentration is correct, considering possible experimental errors and data quality.

(5 marks)

(a)

Percentage error = (|25.30 – 25.00| ÷ 25.00) × 100 = 1.2% (1 mark).

(b)

Award up to 4 marks for a detailed evaluation including the following points:

The result is close to the accepted value, indicating high accuracy (1 mark).

Small percentage error suggests the method was reliable, assuming consistent technique (1 mark).

Possible systematic errors (e.g. misreading burette, improper rinsing of apparatus) could reduce accuracy (1 mark).

Reliability could be confirmed by repeating titrations and obtaining concordant results within ±0.10 cm³ (1 mark).

Total: 5 marks