OCR Specification focus:

‘Define oxidising and reducing agents; construct redox equations using half-equations and oxidation numbers.’

Redox chemistry underpins many inorganic processes, requiring clear understanding of electron transfer, oxidation states, and the construction of balanced equations using reliable, systematic approaches.

Understanding Redox Terminology

Redox processes describe chemical changes involving electron movement. Clarity in terminology is essential because these definitions govern how reactions are interpreted and balanced.

Oxidation: Loss of electrons or an increase in oxidation number during a chemical change.

Oxidation must always be paired with its counterpart, reduction, since electrons cannot be lost without being gained elsewhere in the system.

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

Reduction: Gain of electrons or a decrease in oxidation number during a chemical change.

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

A sentence of ordinary explanation fits here to maintain appropriate spacing between definition blocks, and to reinforce that oxidation and reduction occur simultaneously in all redox reactions.

Oxidising agent: A species that causes oxidation by accepting electrons and is therefore reduced itself.

Understanding oxidising agents allows students to predict which species will draw electrons from others.

Reducing agent: A species that causes reduction by donating electrons and is therefore oxidised itself.

These paired terms help students identify electron flow, a central feature of redox reasoning.

Oxidation Numbers and Their Assignment

Oxidation numbers allow chemists to track electron redistribution even when reactions involve covalent bonding. They do not represent actual charges but serve as a powerful electron-bookkeeping tool.

Key Rules for Oxidation Numbers

The following rules support consistent interpretation of redox changes:

Elements in their uncombined state have an oxidation number of 0.

Monoatomic ions have oxidation numbers equal to their ionic charge.

Oxygen is typically –2, except in peroxides (–1) and in compounds with fluorine.

Hydrogen is typically +1, except when bonded to metals in hydrides (–1).

The sum of oxidation numbers in a compound is 0, and in a polyatomic ion equals the ion charge.

Changes in oxidation numbers reveal whether oxidation or reduction has occurred and help determine electron transfers quantitatively.

Constructing Redox Equations

The specification emphasises constructing redox equations using half-equations and oxidation numbers. Both methods arrive at the same balanced overall equation but suit slightly different contexts.

Using Oxidation Numbers to Balance Redox Changes

This method focuses on comparing oxidation number changes in reactants and products. Students identify which species undergo oxidation and reduction, then balance the total electron change.

Steps include:

Determine oxidation numbers for relevant atoms.

Identify increases (oxidation) and decreases (reduction).

Balance the number of electrons transferred by adjusting stoichiometric coefficients.

Balance remaining atoms and finally balance charge if required.

Using Half-Equations

Half-equations explicitly show the electrons gained or lost, making them especially suitable in aqueous systems where H⁺, OH⁻, and H₂O must be added appropriately.

Half-equation: An equation showing either oxidation or reduction, including explicit electron loss or gain.

One sentence is inserted here before another equation block would appear, maintaining correct formatting boundaries.

Steps in Constructing Half-Equations

In acidic or alkaline media, additional balancing species support charge and mass conservation. The following bullet points outline the systematic approach:

Identify the species undergoing oxidation or reduction.

Write the unbalanced half-equation showing the core chemical change.

Balance atoms other than oxygen and hydrogen.

Add H₂O to balance oxygen atoms.

Add H⁺ (acidic conditions) or OH⁻ (alkaline conditions) to balance hydrogen.

Add electrons to balance charge.

Combine oxidation and reduction half-equations so electron numbers cancel.

Simplify to obtain the overall balanced redox equation.

Recognising Electron Flow in Redox Systems

Electron flow can be deduced by tracking oxidation number changes or analysing half-equations. Both methods must lead to the same final description of oxidation and reduction.

Redox reactions involve simultaneous oxidation and reduction, with electrons transferred from a reducing agent to an oxidising agent.

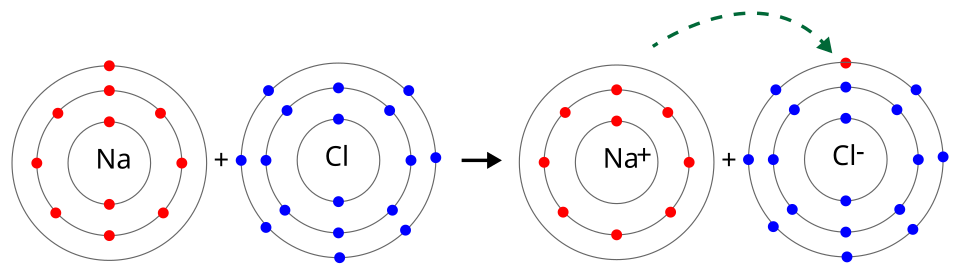

Electron transfer from sodium to chlorine is shown, linking loss of electrons (oxidation) and gain of electrons (reduction) to the roles of reducing and oxidising agents. The diagram also includes ionic bonding context, which goes beyond this subsubtopic but does not affect the redox interpretation. Source

Identifying Oxidising and Reducing Agents in Practice

Identifying the agent responsible for each process is fundamental to meeting the specification requirement.

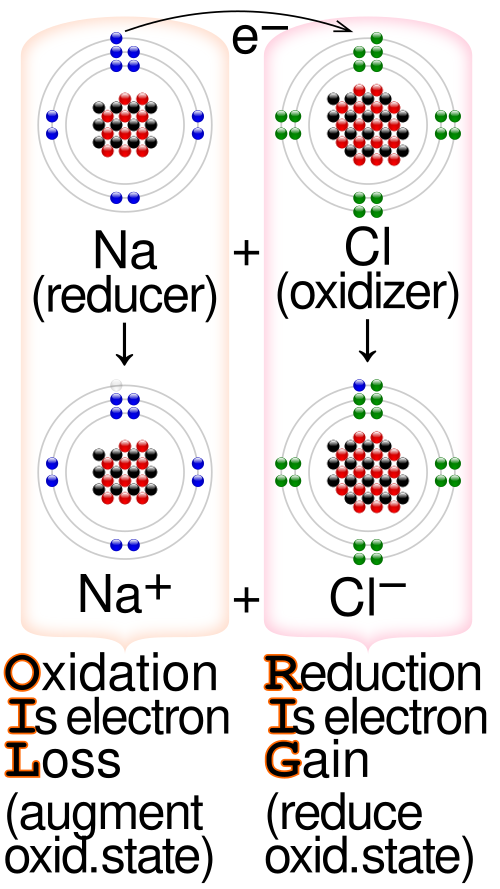

A useful way to remember the electron definitions is OIL RIG: Oxidation Is Loss (of electrons), Reduction Is Gain (of electrons).

The diagram summarises the OIL RIG mnemonic and labels which species is oxidised or reduced, and which acts as the oxidising or reducing agent. It supports quick identification before constructing or combining half-equations. Source

Common indicators include:

A species whose oxidation number increases acts as the reducing agent.

A species whose oxidation number decreases acts as the oxidising agent.

Species containing highly electronegative elements often function as strong oxidising agents.

Metal species, particularly in lower oxidation states, frequently behave as reducing agents.

Importance of Balancing Charge and Mass

Redox equations must conserve both atoms and charge, meaning careful inspection is needed while constructing equations. Imbalances usually indicate missing electrons, missing water, or incorrect stoichiometric coefficients.

Typical Redox Contexts

Redox balancing applies to a wide range of chemical systems essential for A-Level understanding, including:

Metal displacement reactions

Halogen–halide reactions

Transition metal ion redox changes

Acidified manganate(VII) and dichromate(VI) processes

Disproportionation and comproportionation reactions

These systems reinforce the importance of systematic balancing and correct interpretation of oxidation states throughout redox chemistry.

FAQ

Oxidation was originally defined as the gain of oxygen, but this definition is too limited for modern chemistry.

Redox reactions are now defined by electron transfer or changes in oxidation number, which apply to reactions without oxygen. For example, a metal atom losing electrons in a displacement reaction is oxidised even though no oxygen is present.

This broader definition allows redox concepts to be applied consistently across ionic, covalent, and aqueous systems.

The reducing agent can be identified by analysing oxidation numbers alone.

Find the species whose oxidation number increases

An increase in oxidation number means loss of electrons

The species losing electrons is the reducing agent

This approach is especially useful in complex equations where writing full half-equations would be time-consuming.

Electrons are shown in half-equations but not in overall redox equations.

This is because electrons are transferred internally between species and are not present as free particles in the final reaction. When half-equations are combined, electrons cancel out to conserve charge.

Including electrons in the final equation would imply they are reaction products, which is chemically incorrect.

In a simple redox reaction, oxidation and reduction occur in different species.

In disproportionation, the same species is both oxidised and reduced. This can be identified by the element forming two products with different oxidation numbers.

Recognising disproportionation relies on oxidation number analysis rather than half-equations alone.

Redox reactions involve movement of charged particles, so electrical charge must be conserved.

If charge is not balanced, it usually indicates missing electrons or incorrectly added H⁺ or OH⁻ ions. Balancing charge ensures the equation accurately represents electron transfer.

This is particularly important in aqueous redox reactions, where ions and electrons play a central role.

Practice Questions

Magnesium reacts with copper(II) sulfate solution.

(a) State which species is oxidised and which species is reduced in this reaction.

(b) Identify the oxidising agent.

(2 marks)

(a)

Magnesium is oxidised. (1 mark)

Copper(II) ions are reduced. (1 mark)

(b)

Copper(II) ions / Cu²⁺ identified as the oxidising agent. (1 mark)

Maximum 2 marks awarded overall.

In acidic solution, iron(II) ions react with dichromate(VI) ions to form iron(III) ions and chromium(III) ions.

(a) Write the half-equation for the oxidation of iron(II) to iron(III).

(b) Write the half-equation for the reduction of dichromate(VI) to chromium(III) in acidic conditions.

(c) Explain how oxidation numbers show that iron(II) has been oxidised in this reaction.

(5 marks)

(a)

Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺ + e⁻ (1 mark)

(b)

Cr₂O₇²⁻ + 14H⁺ + 6e⁻ → 2Cr³⁺ + 7H₂O (2 marks)

One mark for correct species and electrons

One mark for correct balancing with H⁺ and H₂O

(c)

Iron oxidation number increases from +2 to +3. (1 mark)

Increase in oxidation number indicates oxidation. (1 mark)

Total: 5 marks