OCR Specification focus:

‘Use bond lengths, enthalpy of hydrogenation, and resistance to addition to support the delocalised benzene model.’

Experimental evidence shows benzene cannot be explained by simple alternating double bonds, instead supporting a delocalised π system that accounts for its unusual stability and reactivity.

The Need for Experimental Evidence

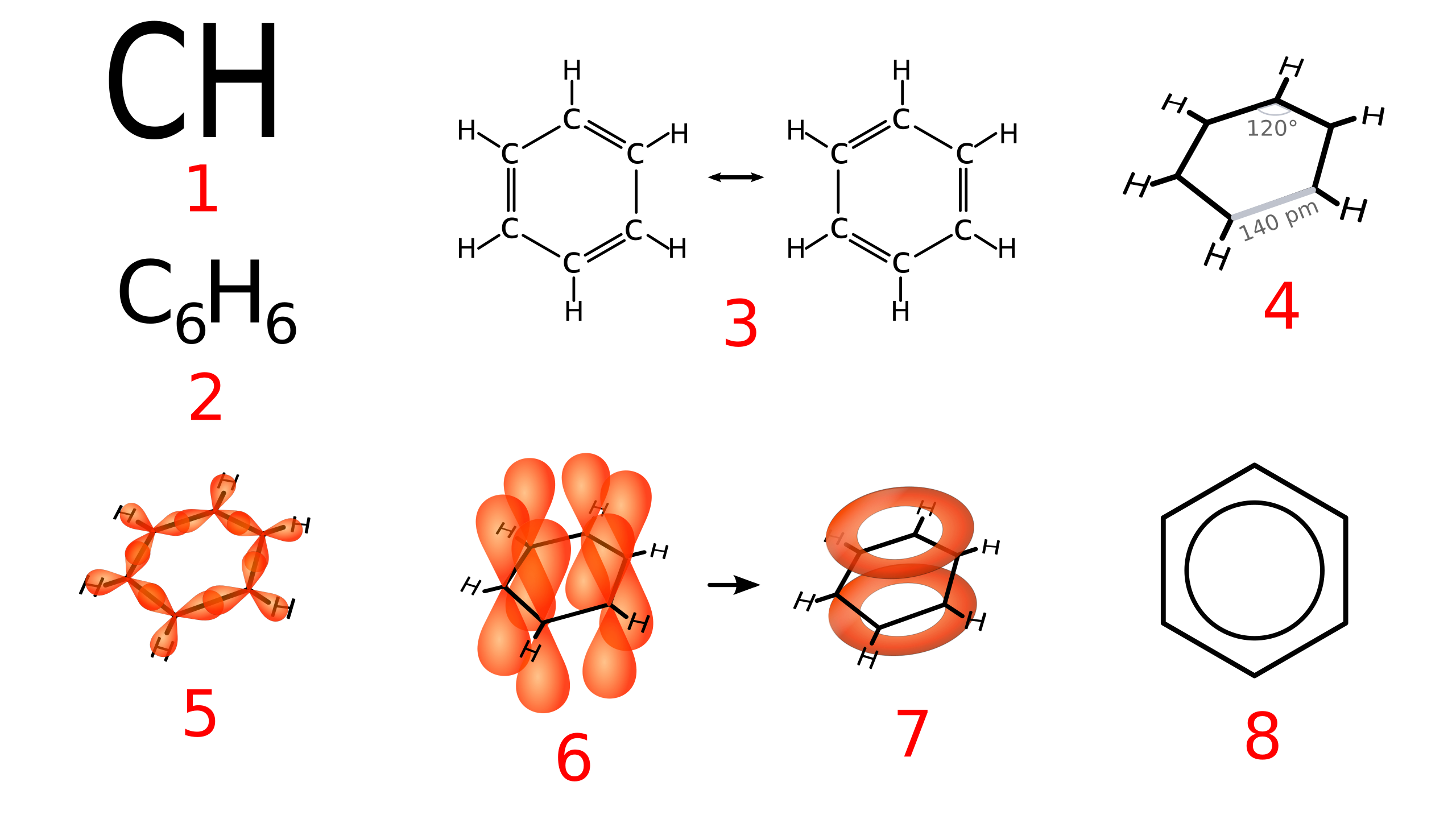

Early structural models of benzene attempted to explain its formula, C₆H₆, using alternating single and double bonds. While these Kekulé structures account for valency, experimental measurements reveal discrepancies that cannot be explained by localised double bonds alone.

The delocalised model proposes that electrons in the π system are spread evenly over the entire ring, rather than confined between specific carbon atoms. Several independent experimental observations support this model and collectively provide strong evidence for delocalisation in benzene.

Carbon–Carbon Bond Lengths in Benzene

One of the strongest pieces of experimental evidence comes from precise measurements of carbon–carbon bond lengths using techniques such as X-ray diffraction.

In alkenes, a C=C double bond is shorter than a C–C single bond because increased electron density between the nuclei pulls the atoms closer together. Typical bond lengths are:

C–C single bond: approximately 0.154 nm

C=C double bond: approximately 0.134 nm

If benzene contained alternating single and double bonds, two distinct bond lengths would be observed. Instead, all six carbon–carbon bonds in benzene are found to be identical, each measuring approximately 0.139 nm, which is intermediate between single and double bond lengths.

This diagram highlights benzene’s planar hexagonal structure with six identical C–C bond lengths, providing direct structural evidence for a delocalised π system rather than alternating single and double bonds. Source

Delocalisation: The spreading of electrons over more than two atoms, resulting in bonds that are intermediate in strength and length between single and double bonds.

This uniform bond length provides direct structural evidence that the π electrons are not localised, supporting the delocalised benzene model rather than the Kekulé structure.

Enthalpy of Hydrogenation Evidence

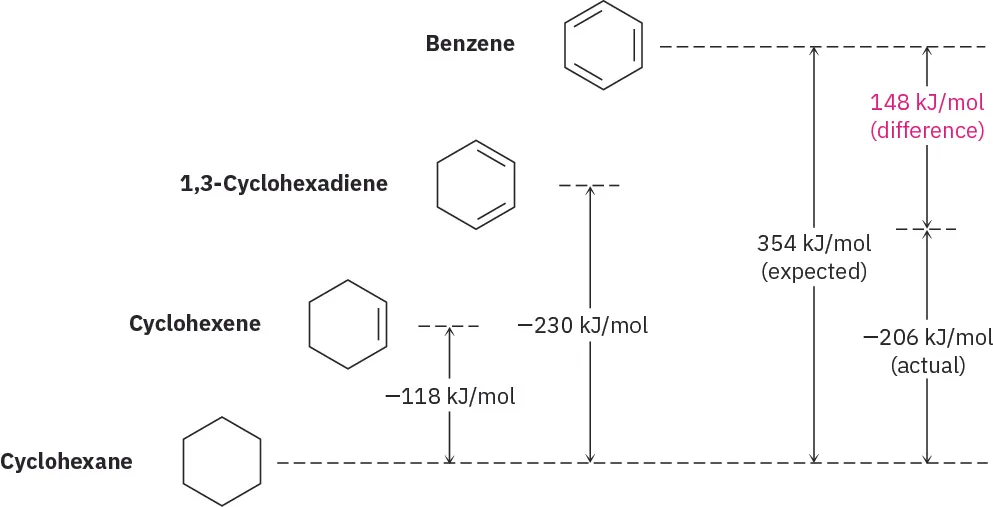

Further evidence comes from studying the enthalpy of hydrogenation of benzene and comparing it with that of similar compounds.

Hydrogenation is the reaction of an unsaturated compound with hydrogen to form a saturated compound. For alkenes, this reaction releases a predictable amount of energy per C=C bond.

Enthalpy of hydrogenation: The enthalpy change when one mole of an unsaturated compound reacts completely with hydrogen under standard conditions.

Cyclohexene, which contains one C=C bond, has an enthalpy of hydrogenation of approximately –120 kJ mol⁻¹. If benzene contained three isolated C=C bonds, its expected enthalpy of hydrogenation would be around –360 kJ mol⁻¹.

However, experimental measurements show that the enthalpy of hydrogenation of benzene is only about –208 kJ mol⁻¹.

Enthalpy change (ΔH) = Energy of products − Energy of reactants

ΔH = Enthalpy change in kJ mol⁻¹

This lower-than-expected value indicates that benzene is significantly more stable than predicted by the Kekulé model. The extra stability is referred to as delocalisation energy, arising from the evenly spread π electrons across the ring.

Stability and Delocalisation Energy

The difference between the expected enthalpy of hydrogenation (–360 kJ mol⁻¹) and the observed value (–208 kJ mol⁻¹) represents the additional stability of benzene due to delocalisation.

The diagram shows that benzene releases less energy on hydrogenation than expected for three C=C bonds, demonstrating additional stabilisation from delocalised π electrons. Source

This energy difference demonstrates that breaking the delocalised π system requires extra energy, making benzene thermodynamically more stable than compounds with localised double bonds.

Key implications of this stability include:

Lower reactivity towards reactions that would disrupt the π system

Preference for reactions that preserve delocalisation

Greater resistance to processes typical of alkenes

Resistance to Addition Reactions

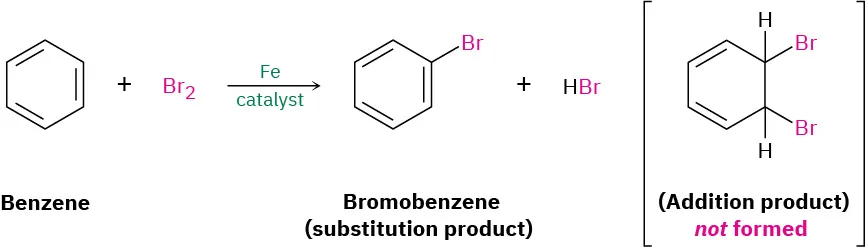

Alkenes typically undergo electrophilic addition reactions, where the π bond breaks to form two new σ bonds. If benzene contained three isolated double bonds, similar addition reactions would be expected.

Experimentally, benzene shows a strong resistance to addition reactions, such as addition of bromine or hydrogen, under normal conditions. Instead, benzene reacts primarily via electrophilic substitution, which preserves the delocalised π system.

This reaction scheme illustrates benzene’s resistance to electrophilic addition, showing substitution with bromine in the presence of a catalyst while preserving the delocalised π system. Source

This behaviour contrasts sharply with alkenes, which readily decolourise bromine water at room temperature. Benzene does not do so without a catalyst, providing further evidence that its bonding is fundamentally different.

Linking Experimental Evidence to the Delocalised Model

Each experimental observation supports the same conclusion:

Equal bond lengths show electrons are evenly distributed

Lower enthalpy of hydrogenation indicates enhanced stability

Resistance to addition demonstrates reluctance to disrupt the π system

Together, these findings cannot be explained by alternating single and double bonds. They are fully consistent with a delocalised π system formed by overlap of p orbitals around the ring, producing a continuous region of electron density above and below the plane of the benzene molecule.

This experimental evidence underpins the modern understanding of benzene’s structure and explains both its unusual stability and distinctive chemical behaviour.

FAQ

X-ray diffraction measures the positions of atomic nuclei within a crystal by analysing how X-rays are scattered by electron density.

Because bond length depends on electron density between atoms, this technique can distinguish between single and double bonds. The identical C–C bond lengths observed in benzene cannot be explained by alternating bonds, making the evidence direct and structural rather than inferred from reactivity.

Delocalisation energy refers to the extra stability benzene has due to its delocalised π electrons.

It is not measured directly but inferred by comparing the expected enthalpy of hydrogenation (based on three C=C bonds) with the experimentally observed value. The difference between these values represents the stabilisation from delocalisation.

Hydrogenation of benzene would require breaking the delocalised π system, which is energetically unfavourable.

As a result:

Higher temperatures and pressures are needed

A metal catalyst is required

The reaction is much slower than alkene hydrogenation

This reduced reactivity reflects the stability of the delocalised structure.

If benzene rapidly alternated between two Kekulé structures, average bond lengths might be expected.

However, experimental techniques show permanent, identical bond lengths rather than fluctuating values. This indicates a true delocalised system rather than fast switching between localised structures.

Resistance to addition is based on observed reaction behaviour under controlled conditions.

Experiments show that benzene does not readily undergo addition reactions typical of alkenes, even when exposed to reagents like bromine. This consistent experimental outcome supports the delocalised model by demonstrating the energetic cost of disrupting the π system.

Practice Questions

Benzene has six identical carbon–carbon bond lengths. Explain how this observation provides evidence for a delocalised structure rather than a Kekulé structure.

(2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for stating that all C–C bond lengths in benzene are equal or identical.

1 mark for explaining that equal bond lengths show electrons are delocalised around the ring rather than localised in alternating single and double bonds.

Experimental data shows that benzene has a lower enthalpy of hydrogenation than expected for a compound containing three C=C bonds.

Using this information and benzene’s reactivity, explain how experimental evidence supports the delocalised model of benzene.

(5 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for stating that benzene’s enthalpy of hydrogenation is less exothermic than expected for three C=C bonds.

1 mark for recognising that this shows benzene is more stable than predicted by a Kekulé model.

1 mark for linking this extra stability to delocalisation of π electrons around the ring.

1 mark for stating that benzene resists electrophilic addition reactions.

1 mark for explaining that addition would disrupt the delocalised π system, so benzene prefers reactions that preserve delocalisation.

Maximum 5 marks.