OCR Specification focus:

‘Write electrophilic substitution mechanisms, including NO₂⁺ formation and X⁺ electrophile with halogen carriers.’

Aromatic compounds undergo characteristic electrophilic substitution reactions, preserving benzene’s delocalised π-system while allowing substitution, rather than addition, through carefully defined multi-step reaction mechanisms.

Electrophilic Substitution in Benzene

Benzene reacts differently from alkenes due to its delocalised π-system, which provides extra stability. Rather than undergoing addition reactions that would disrupt this system, benzene typically reacts via electrophilic substitution.

Electrophilic substitution involves:

Attack of an electrophile on the aromatic ring

Temporary loss of aromaticity

Subsequent restoration of the delocalised π-system

This reaction type is central to both nitration and halogenation of benzene.

Key Mechanistic Features

The π-System as a Nucleophile

The benzene ring contains six delocalised π-electrons above and below the plane of the ring. These electrons are regions of high electron density and can attract positively charged or electron-deficient species.

Electrophile: An electron-deficient species that accepts an electron pair to form a covalent bond.

In electrophilic substitution, the benzene π-system acts as a nucleophile, donating electron density to the electrophile.

Nitration of Benzene

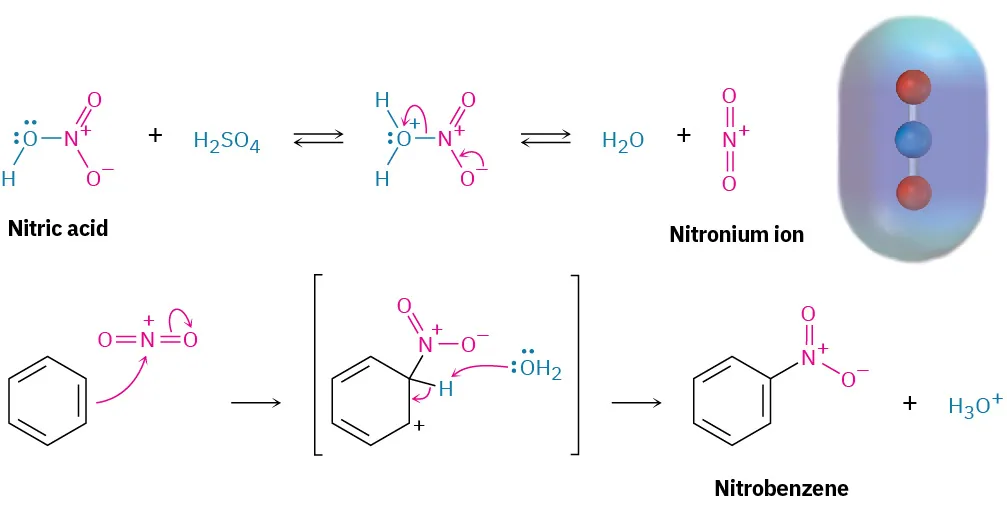

Generation of the Electrophile

Nitration requires a powerful electrophile because benzene is relatively unreactive. This electrophile is the nitronium ion, NO₂⁺, generated in situ using concentrated acids.

Concentrated nitric acid reacts with concentrated sulfuric acid, which acts as a catalyst and dehydrating agent.

Nitronium ion (NO₂⁺): A positively charged electrophile responsible for nitration of aromatic rings.

Sulfuric acid protonates nitric acid, leading to loss of water and formation of NO₂⁺.

This diagram shows generation of the nitronium ion (NO₂⁺) using mixed acids and its electrophilic substitution with benzene via a sigma complex. The small electrostatic potential image of NO₂⁺ provides extra visual detail not required by the OCR syllabus. Source

Mechanism Step 1: Formation of the Sigma Complex

The π-electrons of benzene attack the nitronium ion

A new C–N bond forms

Aromaticity is temporarily lost

A sigma complex (arenium ion) forms, with a positive charge delocalised around the ring

Sigma complex: A positively charged intermediate formed when an electrophile bonds to an aromatic ring, temporarily disrupting delocalisation.

This step is slow and energy-demanding because aromatic stability is lost.

Mechanism Step 2: Loss of a Proton

A base (often HSO₄⁻) removes a proton from the ring

The C–H bond electrons rejoin the π-system

Aromaticity is restored

Nitrobenzene is formed

This step is rapid and releases energy due to restoration of the delocalised π-system.

Halogenation of Benzene

Role of Halogen Carriers

Halogens alone are not sufficiently reactive to attack benzene. A halogen carrier, such as iron or aluminium halides, is required to generate a strong electrophile.

Common examples include:

FeBr₃ or AlBr₃ for bromination

FeCl₃ or AlCl₃ for chlorination

Halogen carrier: A catalyst that polarises a halogen molecule to generate a positive halogen electrophile.

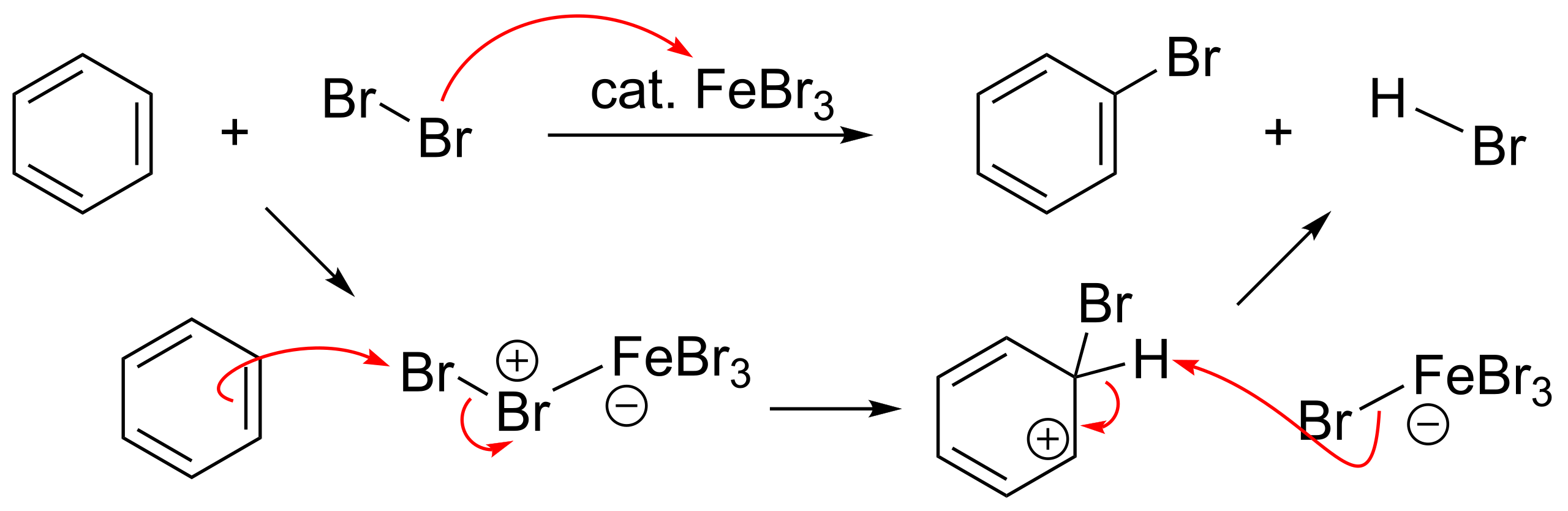

Formation of the Halogen Electrophile

The halogen carrier reacts with the halogen molecule, producing a positively charged halogen species, X⁺, where X is Cl or Br.

This mechanism diagram shows electrophilic substitution during benzene bromination using a halogen carrier to generate Br⁺. Curly arrows indicate sigma complex formation and deprotonation restoring aromaticity. Source

This electrophile is sufficiently electron-deficient to react with the benzene π-system.

Mechanism of Halogenation

Step 1: Electrophilic Attack

The benzene π-system attacks the X⁺ electrophile

A C–X bond forms

A sigma complex is produced

Aromaticity is temporarily lost

As in nitration, this is the rate-determining step due to loss of aromatic stability.

Step 2: Deprotonation and Regeneration

A halide ion or the catalyst removes a proton

The delocalised π-system reforms

The halogenated benzene is produced

The halogen carrier catalyst is regenerated

This regeneration confirms the carrier acts as a true catalyst and is not consumed.

Comparison of Nitration and Halogenation Mechanisms

Both mechanisms share common structural features:

Electrophile generation prior to ring attack

Formation of a sigma complex intermediate

Temporary loss and restoration of aromaticity

Final deprotonation step

Key differences include:

The nature of the electrophile (NO₂⁺ vs X⁺)

Use of mixed acids for nitration

Requirement of a halogen carrier for halogenation

Importance of Mechanistic Accuracy

For OCR A-Level Chemistry, mechanisms must be:

Clearly drawn with curly arrows showing electron movement

Balanced in terms of charges and atoms

Labelled to identify electrophiles and intermediates

Understanding these mechanisms explains benzene’s resistance to addition reactions and its preference for substitution, reinforcing the importance of delocalisation in aromatic chemistry.

FAQ

The sigma complex forms when benzene temporarily loses its aromaticity. This requires a large input of energy because the delocalised π-system is disrupted.

This step has the highest activation energy in the mechanism, making it slower than deprotonation, which rapidly restores aromatic stability.

Benzene’s delocalised π-system makes it significantly more stable than the localised π-bond in alkenes.

As a result, benzene resists reaction unless the electrophile is very electron-deficient, such as NO₂⁺ or X⁺ generated using catalysts.

Halogen carriers act as catalysts by temporarily forming complexes with halogen molecules.

After electrophilic substitution and deprotonation:

The carrier is regenerated

It is available to activate another halogen molecule

This confirms its catalytic role rather than a reactant.

Temperature control prevents further substitution of the aromatic ring.

At higher temperatures, multiple nitro groups may be introduced, forming dinitro or trinitro compounds. Controlled conditions favour monosubstitution only.

Electrophilic substitution restores aromaticity after temporary disruption.

Addition reactions would permanently break the delocalised π-system, producing a much less stable compound. Substitution allows benzene to retain its energetically favourable structure.

Practice Questions

Describe how the electrophile required for the nitration of benzene is formed from concentrated nitric acid and concentrated sulfuric acid.

(2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

One mark for stating that concentrated sulfuric acid acts as an acid/catalyst to generate the electrophile.

One mark for correctly identifying the electrophile as the nitronium ion, NO₂⁺, formed by loss of water from nitric acid.

Describe the mechanism for the bromination of benzene using a halogen carrier. Your answer should include the role of the halogen carrier and explain how aromaticity is restored.

(5 marks)

Award marks as follows:

One mark for stating that the halogen carrier (e.g. FeBr₃ or AlBr₃) reacts with Br₂ to generate a positive bromine electrophile, Br⁺.

One mark for describing attack of the benzene π-electrons on the electrophile to form a C–Br bond.

One mark for identifying formation of a sigma complex (arenium ion) and temporary loss of aromaticity.

One mark for describing removal of a proton from the sigma complex by a base or halide ion.

One mark for explaining that aromaticity is restored when the delocalised π-system reforms and the catalyst is regenerated.

Accept clear descriptions of electron movement even if curly arrows are not explicitly mentioned in words.