OCR Specification focus:

‘Compare Kekulé and delocalised models: p-orbital overlap forms a π-system; explain evidence and reactivity differences.’

These notes explore benzene’s structure, comparing historical and modern models, explaining π-electron delocalisation, orbital overlap, and how structure influences stability, bond lengths, and chemical reactivity.

The Molecular Structure of Benzene

Benzene has the molecular formula C₆H₆ and is the simplest aromatic hydrocarbon. Early attempts to explain its structure struggled to account for its unusual stability and reactivity. Unlike alkenes, benzene does not readily undergo addition reactions, despite appearing to contain multiple carbon–carbon double bonds.

Each carbon atom in benzene is sp² hybridised, forming:

Three σ (sigma) bonds

A trigonal planar arrangement with bond angles of approximately 120°

Two of these σ bonds are formed with neighbouring carbon atoms, creating a hexagonal ring, and the third is formed with a hydrogen atom. This arrangement leaves one unhybridised p orbital on each carbon atom, perpendicular to the plane of the ring.

The Kekulé Model of Benzene

The earliest widely accepted model of benzene was proposed by August Kekulé in the 19th century. It represents benzene as a six-membered ring with alternating single and double carbon–carbon bonds.

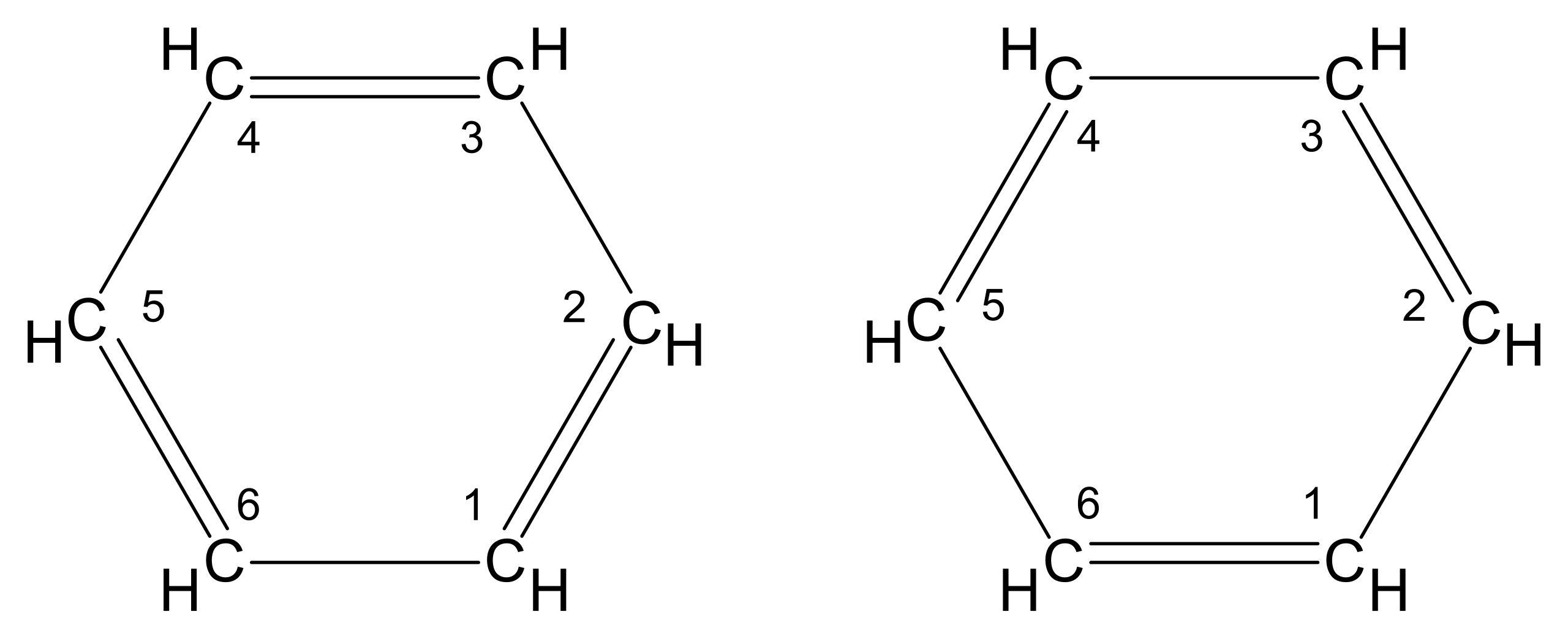

This diagram shows the Kekulé model of benzene, drawn as a hexagon with alternating C–C and C=C bonds. It illustrates the early view of benzene as a cyclohexatriene with localised double bonds. Source

Kekulé model: A structural model of benzene showing alternating C–C single and C=C double bonds around a hexagonal ring.

According to this model:

There are three C=C double bonds and three C–C single bonds

Double bonds are localised between specific carbon atoms

Two equivalent Kekulé structures can be drawn by alternating the positions of the double bonds

This model successfully explains why benzene has six carbon atoms bonded in a ring and why each carbon forms three bonds. However, it fails to explain key experimental observations.

One major limitation is that the Kekulé model predicts two different carbon–carbon bond lengths, corresponding to single and double bonds. Experimental data show this is not the case.

Experimental Bond Length Evidence

Measurements using X-ray diffraction reveal that all six carbon–carbon bonds in benzene have the same length of approximately 0.139 nm. This value lies between:

A typical C–C single bond (0.154 nm)

A typical C=C double bond (0.134 nm)

This evidence contradicts the Kekulé model and suggests that bonding electrons are not confined between specific carbon atoms. A more accurate model is required to explain this equivalence.

The Delocalised Model of Benzene

The modern explanation of benzene’s structure is the delocalised model, sometimes referred to as the resonance model.

Delocalisation: The spreading of electrons over several atoms, where electrons are not confined to a single bond or atom.

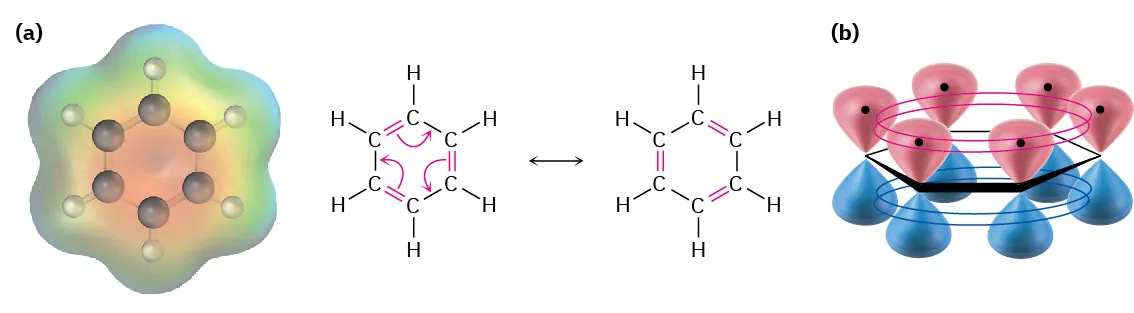

In benzene:

Each carbon atom contributes one electron from its unhybridised p orbital

These p orbitals overlap sideways around the ring

This overlap creates a continuous π system above and below the plane of the ring

This figure illustrates how sideways overlap of six p orbitals forms a continuous π system above and below the benzene ring. The orbital diagram explains electron delocalisation; the electrostatic surface adds extra detail beyond syllabus requirements. Source

π system: A region of electron density formed by the sideways overlap of p orbitals, allowing electrons to move freely over multiple atoms.

The six π electrons are delocalised over all six carbon atoms, meaning:

All C–C bonds are equivalent

Each bond has partial double bond character

The structure is more stable than any arrangement with localised double bonds

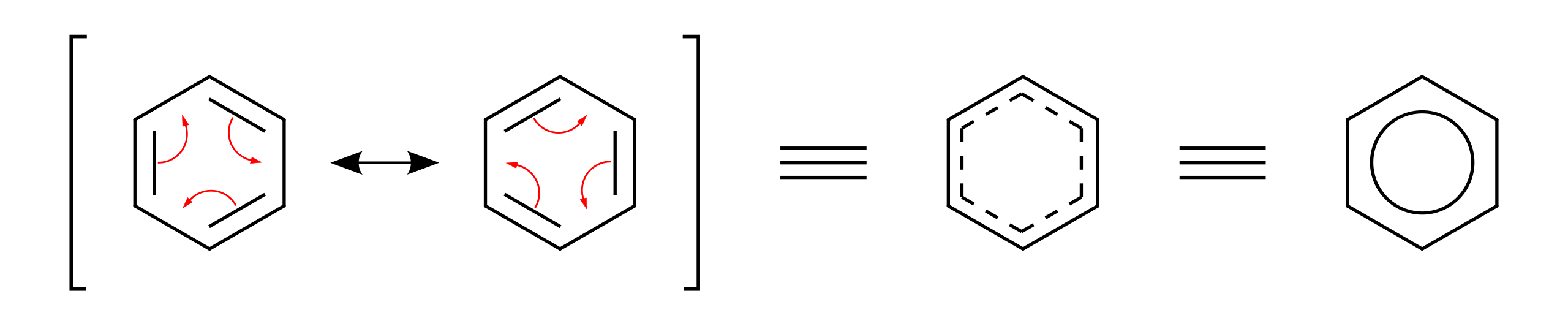

This delocalisation is often represented by a hexagon with a circle inside, symbolising the shared π electrons.

This diagram compares resonance drawings with a delocalised representation of benzene. It reinforces that π electrons are shared across the entire ring rather than confined to individual double bonds. Source

p-Orbital Overlap and Stability

The delocalised model relies on effective p-orbital overlap. For this to occur:

All carbon atoms must be coplanar

p orbitals must be parallel and close enough to overlap

Continuous overlap must exist around the entire ring

This arrangement allows π electrons to be spread evenly across the molecule. Delocalisation lowers the overall energy of benzene compared to hypothetical cyclohexatriene structures, making benzene thermodynamically more stable.

This increased stability is a defining feature of aromatic compounds and explains why benzene resists reactions that would disrupt its π system.

Reactivity Differences Explained by Structure

The Kekulé model predicts that benzene should behave like a typical alkene and undergo addition reactions readily. In reality, benzene shows very low reactivity towards addition reactions such as hydrogenation or halogen addition.

The delocalised model explains this behaviour:

Addition reactions would break the continuous π system

Loss of delocalisation would reduce stability

As a result, these reactions are energetically unfavourable

Instead, benzene typically undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions, where:

One hydrogen atom is replaced

The aromatic π system is preserved

This contrast in reactivity between benzene and alkenes provides strong evidence in favour of the delocalised model over the Kekulé model.

Comparing the Two Models

Key differences between the models include:

Bonding: Kekulé assumes localised double bonds; the delocalised model involves shared π electrons

Bond lengths: Kekulé predicts alternating lengths; experimentally, all are equal

Stability: Delocalisation accounts for benzene’s enhanced stability

Reactivity: Only the delocalised model explains benzene’s resistance to addition reactions

The delocalised model is therefore accepted as the accurate description of benzene’s structure, fully consistent with experimental evidence and observed chemical behaviour.

FAQ

All six carbon atoms in benzene are sp² hybridised and arranged in a flat, planar ring.

This geometry allows each unhybridised p orbital to be parallel and close enough to overlap with its neighbours, creating a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals.

Because the ring is symmetrical, each carbon contributes equally to the delocalised π system, resulting in identical bonding and electron distribution throughout the molecule.

Delocalisation relies on effective sideways overlap of p orbitals.

If benzene were not planar, the p orbitals would not align properly, preventing continuous overlap around the ring.

This would disrupt the π system and reduce delocalisation, making the molecule less stable. Planarity is therefore essential for maintaining benzene’s aromatic stability.

In benzene, the six π electrons are shared across all six carbon–carbon bonds rather than being confined to three specific double bonds.

As a result, each C–C bond has:

Some σ bond character

Some π bond character

This leads to bond lengths that are intermediate between single and double bonds, giving every bond partial double bond character.

Kekulé structures are still used because they help show how electrons might be arranged if delocalisation did not occur.

Drawing two equivalent Kekulé structures emphasises that no single structure accurately represents benzene.

They are a useful stepping stone to understanding delocalisation, even though the real structure is a hybrid rather than rapidly switching between forms.

Cyclohexatriene would contain three isolated C=C bonds with localised electrons.

In benzene, delocalisation spreads the π electrons over the entire ring, lowering the overall energy of the molecule.

This extra stability arises because:

Electron density is spread more evenly

No single bond bears excessive electron density

This makes benzene significantly more stable than any structure with localised double bonds.

Practice Questions

Benzene has six carbon–carbon bonds that are all the same length.

Explain why this observation supports the delocalised model of benzene rather than the Kekulé model.

(2 marks)

States that all C–C bonds in benzene are identical in length. (1 mark)

Explains that this is because π electrons are delocalised over the whole ring rather than localised in alternating single and double bonds. (1 mark)

Describe and compare the Kekulé and delocalised models of benzene.

In your answer, you should refer to p-orbital overlap, the π system, and how each model explains the reactivity of benzene.

(5 marks)

Kekulé model described as a ring with alternating C–C single and C=C double bonds. (1 mark)

Delocalised model described as involving sideways overlap of p orbitals forming a continuous π system above and below the ring. (1 mark)

States that π electrons are delocalised over all six carbon atoms in the delocalised model. (1 mark)

Explains that delocalisation makes all C–C bonds equivalent in length. (1 mark)

Explains that benzene undergoes substitution rather than addition because breaking the delocalised π system would reduce stability. (1 mark)

Maximum of 5 marks.