OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain phenol’s weak acidity, rapid bromination/nitration, and 2,4-directing OH; predict products using directing rules.’

Phenol is an aromatic compound featuring a hydroxyl (–OH) group directly bonded to a benzene ring. Its properties, including acidity, electrophilic reactivity, and substitution patterns, differ significantly from those of simple alcohols, influencing its behaviour in organic reactions.

Acidity of Phenol

Phenol is a weak acid, weaker than carboxylic acids but stronger than alcohols.

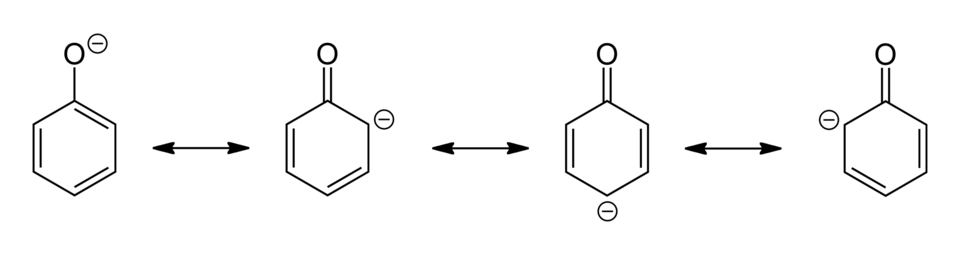

Diagram showing the resonance structures of the phenoxide ion. Delocalisation of the negative charge into the aromatic ring stabilises the conjugate base of phenol, explaining why phenol is more acidic than simple alcohols. This visual focuses on the skeletal form and does not include extra reactions not required by the syllabus. Source

The –OH group can donate a proton (H+) to form the phenoxide ion, which is stabilised by delocalisation of the negative charge into the benzene ring.

Phenoxide ion: The conjugate base of phenol, formed when the hydrogen ion from the hydroxyl group is lost, with negative charge delocalised across the aromatic ring.

The acidity of phenol is higher than alcohols due to resonance stabilisation: the lone pair of electrons on oxygen overlaps with the π-system of the benzene ring, dispersing the negative charge.

Alcohols: R–OH → R–O– + H+ (less stable conjugate base)

Phenol: C6H5–OH → C6H5–O– + H+ (stabilised by delocalisation)

Factors affecting phenol acidity:

Electron-withdrawing substituents increase acidity by stabilising the phenoxide ion.

Electron-donating substituents reduce acidity by destabilising the negative charge.

Reactivity of Phenol

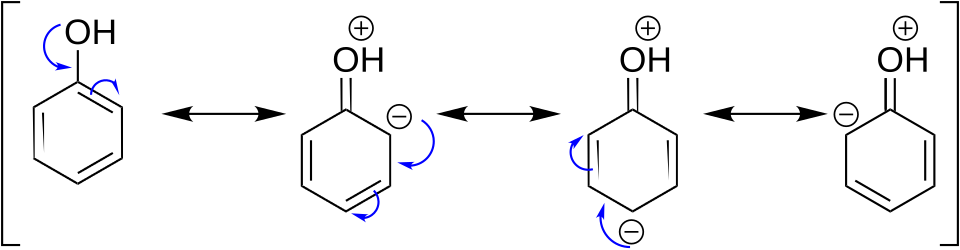

Phenol is more reactive than benzene towards electrophilic substitution because the –OH group activates the ring by electron donation through resonance.

Bromination of Phenol

Phenol undergoes rapid bromination without a halogen carrier, unlike benzene. The reaction forms 2,4,6-tribromophenol as a white precipitate.

Mechanism summary:

Electron density on the ring increases due to –OH activation.

Bromine (Br2) acts as the electrophile and attacks the ring at the activated positions (ortho and para).

No Lewis acid catalyst is required.

Bromination of phenol: C6H5OH + 3Br2 → C6H2Br3OH + 3HBr

This reaction is useful for identifying phenol in qualitative analysis.

Nitration of Phenol

Phenol reacts with dilute nitric acid at room temperature, giving a mixture of 2-nitrophenol and 4-nitrophenol. Concentrated acid and higher temperatures are unnecessary because the ring is highly activated.

The –OH group directs electrophiles to the ortho and para positions due to increased electron density at these sites.

Only small quantities of meta-substituted products are formed in special conditions because –OH is an ortho/para-directing group.

Directing Effects of the –OH Group

The hydroxyl group on phenol is an activating, ortho/para-directing substituent in electrophilic aromatic substitution.

Resonance structures of phenol illustrating how the lone pair on oxygen donates electron density into the aromatic ring. This increases electron density at the ortho and para positions, rationalising the activating and directing effects of the –OH substituent in electrophilic substitution reactions. Some general aromatic resonance detail is shown, but the focus supports only what is needed for this subsubtopic. Source

Electron donation occurs via resonance, pushing electron density into the ring at the ortho and para positions.

This makes these positions more nucleophilic and favours attack by electrophiles.

Predicting Products

When considering reactions such as bromination or nitration:

Ortho position: Adjacent to –OH

Para position: Opposite –OH

Meta position: Not favoured; low electron density here prevents significant substitution

Example: Bromination produces predominantly 2,4,6-tribromophenol.

Example: Nitration produces a mixture of 2-nitrophenol and 4-nitrophenol.

Summary of Directing Effects

–OH group: Activating, ortho/para-directing

Electrophilic substitution occurs faster than in benzene

Meta substitution is unfavourable

Factors Influencing Reactivity

Resonance stabilisation of the phenoxide ion enhances acidity.

Electron donation from –OH increases the electron density of the benzene ring, favouring electrophilic substitution.

Steric effects can influence substitution patterns, particularly at the ortho positions if bulky substituents are present.

Key Points

Phenol is more acidic than alcohols due to delocalisation stabilising the phenoxide ion.

It undergoes rapid electrophilic substitution at the ortho and para positions without the need for halogen carriers or concentrated acid.

The –OH group is an activating substituent and an ortho/para director, which determines the orientation of products in bromination and nitration reactions.

Phenol’s unique properties make it a useful compound in both laboratory identification and organic synthesis.

FAQ

Electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) increase phenol’s acidity by stabilising the phenoxide ion through delocalisation of the negative charge.

Examples include nitro (–NO2) or cyano (–CN) groups.

EWGs pull electron density away from the ring, reducing electron density on the oxygen and making the loss of H+ more favourable.

The more strongly electron-withdrawing and the closer the group is to the –OH, the greater the increase in acidity.

The –OH group activates the aromatic ring via resonance, increasing electron density particularly at the ortho and para positions.

Bromine acts as the electrophile and reacts readily without a Lewis acid catalyst.

The reaction is much faster than for benzene due to this activation.

This property allows for simple identification reactions in the lab.

Steric hindrance occurs when bulky substituents on the ring impede electrophile access to certain positions.

Ortho positions are more crowded, so para substitution may dominate if space is limited.

Bulky groups can slow the rate of reaction or favour substitution at less hindered positions.

This effect is important when predicting products for substituted phenols.

The –OH group is strongly activating due to electron donation via resonance, raising the electron density of the ring.

This makes the ring more reactive toward electrophiles like NO2+.

Benzene lacks this activation, so concentrated acid and elevated temperature are needed to generate the electrophile and promote reaction.

Phenol’s higher reactivity allows mild conditions to achieve substitution.

Yes, phenol can form hydrogen bonds due to the –OH group.

Hydrogen bonding occurs between phenol molecules and with water molecules.

This contributes to its higher boiling point compared to benzene and moderate water solubility.

Hydrogen bonding also slightly stabilises the phenoxide ion when phenol dissociates.

Practice Questions

Explain why phenol is more acidic than ethanol. (2 marks)

1 mark: States that the phenoxide ion is stabilised by resonance.

1 mark: Explains that ethanol’s conjugate base (ethoxide ion) is not resonance stabilised.

Phenol reacts with bromine water to give 2,4,6-tribromophenol.

a) State the colour change observed during this reaction.

b) Explain why bromine reacts more readily with phenol than with benzene.

c) Draw the structural formula of 2,4,6-tribromophenol.

(5 marks)

a) 1 mark: Colour change from orange/brown to colourless or formation of a white precipitate.

b) 2 marks:

1 mark: –OH group donates electron density into the benzene ring via resonance.

1 mark: Increased electron density at ortho and para positions makes the ring more reactive to electrophilic substitution.

c) 2 marks: Correct structural formula of 2,4,6-tribromophenol showing bromine atoms at the 2, 4, and 6 positions and the –OH group at position 1.