OCR Specification focus:

‘Amide groups in polyamides undergo acid and base hydrolysis to smaller molecules.’

Polyamide hydrolysis is a key reaction in A-Level Chemistry, showing how condensation polymers break down into smaller molecules under acidic or alkaline conditions.

Hydrolysing Polyamides

Polyamides contain the amide functional group, which is central to understanding how these polymers can be chemically degraded. The amide group features a carbonyl linked to a nitrogen atom, and its reactivity under different conditions dictates the outcome of hydrolysis reactions.

Amide group: A functional group characterised by a carbonyl (C=O) bonded directly to a nitrogen atom (–NH– or –NR–).

Polyamides such as nylon are formed through condensation reactions between dicarboxylic acids and diamines, producing long chains with repeating amide linkages. Hydrolysis breaks these linkages, reversing the condensation process and yielding smaller organic molecules. This process is essential in polymer recycling, degradation studies, and synthetic planning within organic chemistry.

Polyamides contain repeating amide links (–CONH–), and hydrolysis involves breaking these links by adding water across the bond.

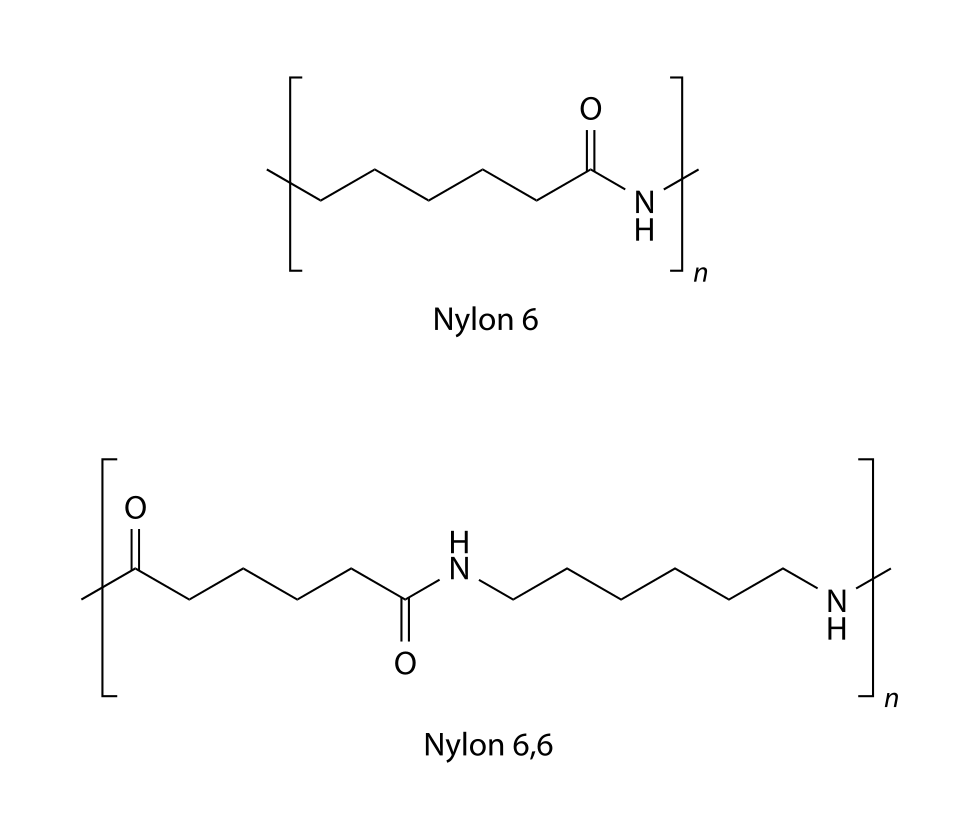

This diagram shows the repeat unit of a common polyamide (nylon 6,6), highlighting the amide linkage (–CONH–) within the polymer chain. Hydrolysis targets this linkage, breaking the polymer into smaller molecules. The inclusion of nylon 6 is additional detail beyond the core syllabus requirement. Source

Why Polyamides Undergo Hydrolysis

The amide bond is relatively stable but can be cleaved under both acidic and basic conditions due to the polar nature of the carbonyl group. The carbonyl carbon is electrophilic, making it susceptible to attack by nucleophiles such as water molecules or hydroxide ions. This cleavage produces fragments that depend on the reaction conditions used.

Acid Hydrolysis of Polyamides

Acid hydrolysis occurs when a polyamide is heated under reflux with a strong acid, typically hydrochloric acid. This condition protonates the carbonyl oxygen, increasing the electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon and making nucleophilic attack more favourable.

Under acidic conditions, the polyamide is broken into:

A dicarboxylic acid (or monocarboxylic acid, depending on the polymer structure)

A protonated amine (forming an ammonium salt)

This reflects the specification requirement that amide groups in polyamides form smaller molecules upon hydrolysis. The process can be explained through the following steps:

Protonation of the amide carbonyl oxygen increases carbonyl reactivity.

Water acts as the nucleophile, attacking the carbonyl carbon.

Subsequent proton transfers break the C–N bond.

The amine fragment becomes fully protonated in strong acid, forming an ammonium ion.

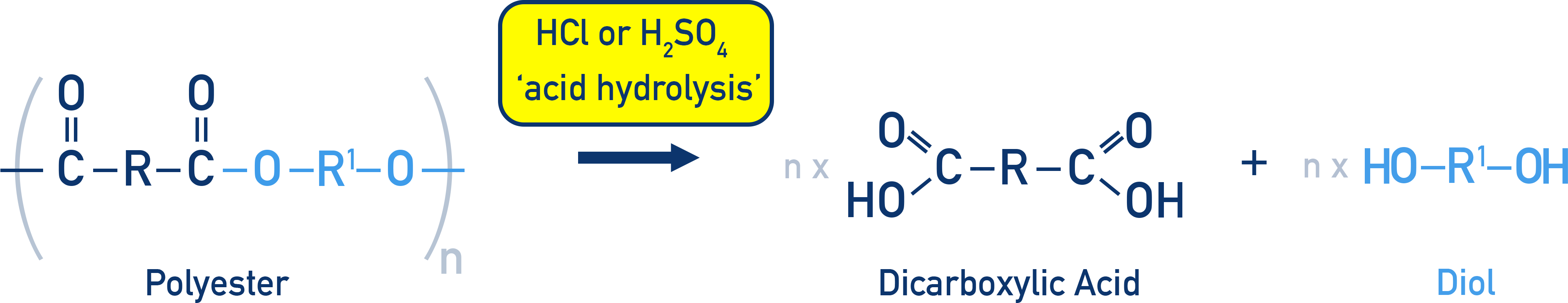

In acid hydrolysis (hot aqueous dilute acid), each amide link is cleaved to give a dicarboxylic acid and a diammonium salt.

This diagram illustrates acid hydrolysis of a polyamide, where heating with aqueous acid breaks amide links. The products are carboxylic acids and protonated amines, shown here as a diammonium salt, matching OCR A‑Level requirements. Source

Because the amine product exists as its ammonium salt, acid hydrolysis is particularly useful when the goal is to obtain cleanly separated acidic and basic fragments.

Base Hydrolysis of Polyamides

Base hydrolysis (also known as alkaline hydrolysis) involves heating the polyamide with aqueous sodium hydroxide. Instead of forming carboxylic acids, the reaction generates:

A carboxylate salt

A free amine

The mechanism differs from acid hydrolysis because hydroxide ions act directly as nucleophiles, attacking the carbonyl carbon without the need for protonation. This leads to irreversible cleavage, as the formation of a stable carboxylate prevents reformation of the amide bond.

Key steps include:

Nucleophilic attack by hydroxide on the carbonyl carbon

Formation of a tetrahedral intermediate

Collapse of the intermediate, breaking the C–N bond

Formation of a carboxylate ion and liberation of the amine

Base hydrolysis is generally faster than acid hydrolysis because hydroxide ions are stronger nucleophiles than water. It is also widely used for analytical breakdown of polyamides due to its efficiency.

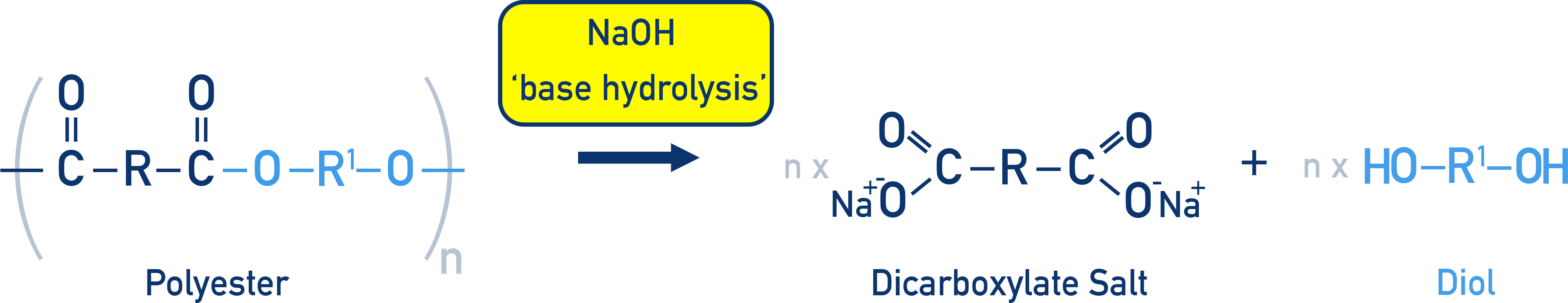

In alkaline hydrolysis (hot aqueous NaOH), the products are a dicarboxylate salt and a diamine rather than the free carboxylic acid.

This diagram shows alkaline hydrolysis of a polyamide using aqueous sodium hydroxide. The amide link is broken to form a carboxylate salt and a diamine, illustrating the contrasting products compared with acid hydrolysis. Source

Comparing Acid and Base Hydrolysis

Understanding the contrasting outcomes of acid and base hydrolysis is crucial. Students should appreciate that both processes cleave the amide linkage but produce different products due to the reaction environment.

Acid hydrolysis produces:

Carboxylic acids

Ammonium salts

Base hydrolysis produces:

Carboxylate ions

Amines

These differences are essential when predicting products in synthetic pathways or analysing polymer degradation.

Reaction Pathways and Structural Outcomes

Hydrolysis always targets the amide bond, the key linkage in polyamides. Regardless of polymer complexity, each hydrolysed amide unit yields fragments corresponding to the original monomers. When dealing with long chains, hydrolysis produces shorter chain molecules or complete monomers, depending on reaction extent.

Because polyamides include repeating units of –CO–NH–, every cleavage event breaks the polymer backbone. Structural analysis of hydrolysed fragments can reveal the type of monomers originally used, which links this subsubtopic to broader skills in polymer identification and synthesis.

Factors Affecting the Hydrolysis of Polyamides

Several factors influence the rate and completeness of hydrolysis:

Temperature: Higher temperatures increase reaction rate due to greater kinetic energy.

Reagent strength: Concentrated acids or strong bases accelerate cleavage.

Polymer structure: Bulky substituents near the amide group reduce accessibility and slow hydrolysis.

Crystallinity: Highly crystalline polymers resist hydrolysis because tightly packed chains restrict reagent penetration.

These factors are relevant when explaining why different polyamides (e.g., nylon-6 vs nylon-6,6) may hydrolyse at different rates in industrial or laboratory settings.

Importance in Synthetic Chemistry

Hydrolysis of polyamides is a fundamental transformation used in synthetic design. Breaking a polymer down into its original monomers or smaller, functional fragments allows chemists to:

Recover monomers for polymer recycling

Modify or analyse polymer structures

Use hydrolysed fragments as intermediates in multi-step organic synthesis

By understanding how amide bonds respond to acidic and basic conditions, students gain essential insight into carbonyl reactivity and mechanisms that appear across organic chemistry.

FAQ

Polyamide amide bonds are relatively unreactive due to resonance stabilisation between the carbonyl group and the nitrogen lone pair. This reduces the electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon.

Heating under reflux provides sufficient energy to overcome this stability and allows the reaction to proceed at a reasonable rate without loss of reactants. Reflux ensures the reaction mixture can be heated for long periods while maintaining a constant volume.

In alkaline hydrolysis, the carboxylic acid produced is immediately converted into a carboxylate ion.

This carboxylate ion is very stable and cannot react with an amine to reform an amide bond under the reaction conditions. As a result, the equilibrium lies strongly towards the products, making base hydrolysis effectively irreversible.

Highly crystalline polyamides have tightly packed chains held together by strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding.

This reduces the ability of water, hydroxide ions, or acids to penetrate the polymer structure, slowing hydrolysis. Amorphous regions are more accessible, so hydrolysis often begins in these less ordered areas before progressing into crystalline regions.

Amide bonds are stabilised by stronger resonance and hydrogen bonding compared with ester bonds.

The nitrogen atom donates electron density into the carbonyl group more effectively than an oxygen atom in esters. This reduces the electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon, making nucleophilic attack less favourable and hydrolysis slower.

Hydrolysis allows polyamides to be chemically broken down into smaller molecules related to their original monomers.

This can be used to:

Identify the monomers used to make an unknown polyamide

Recover monomers for chemical recycling

Study polymer degradation and stability

Such applications rely on controlled hydrolysis rather than complete breakdown under extreme conditions.

Practice Questions

A polyamide contains repeating –CONH– links. Describe what happens when a polyamide is heated under reflux with dilute hydrochloric acid.

(2 marks)

One mark for stating that the amide link is broken by hydrolysis.

One mark for stating that carboxylic acids and ammonium salts are formed (or equivalent wording such as protonated amines).

A sample of a polyamide is hydrolysed in two separate experiments.

In experiment A, the polyamide is heated under reflux with dilute hydrochloric acid.

In experiment B, the polyamide is heated under reflux with aqueous sodium hydroxide.

(a) State the products formed in experiment A.

(b) State the products formed in experiment B.

(c) Explain why the nitrogen-containing product differs between the two experiments.

(5 marks)

(a) Experiment A products (2 marks)

One mark for carboxylic acid.

One mark for ammonium salt / protonated amine.

(b) Experiment B products (2 marks)

One mark for carboxylate salt.

One mark for amine / diamine.

(c) Explanation (1 mark)

One mark for explaining that acidic conditions protonate the amine, forming an ammonium salt, whereas alkaline conditions do not, so the amine remains unprotonated.