OCR Specification focus:

‘Detect alkenes with bromine; identify haloalkanes via aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol.’

Alkenes and haloalkanes undergo characteristic test-tube reactions that allow rapid and reliable qualitative identification. This subsubtopic focuses on the bromine test for unsaturation and the use of silver nitrate with ethanol to identify haloalkanes through their rates of hydrolysis.

Understanding the Purpose of Test-Tube Reactions

Test-tube reactions provide quick, functional-group-level identification without the need for advanced instrumentation. They are particularly important in organic qualitative analysis where structural clues must be obtained from simple chemical observations such as decolourisation, precipitate formation, and reaction rate.

Alkenes: The Bromine Test

Alkenes contain a C=C double bond, which is a region of high electron density and reacts readily with electrophiles. The OCR specification emphasises that alkenes can be detected using bromine.

Electrophile: A species that accepts an electron pair and is attracted to regions of high electron density.

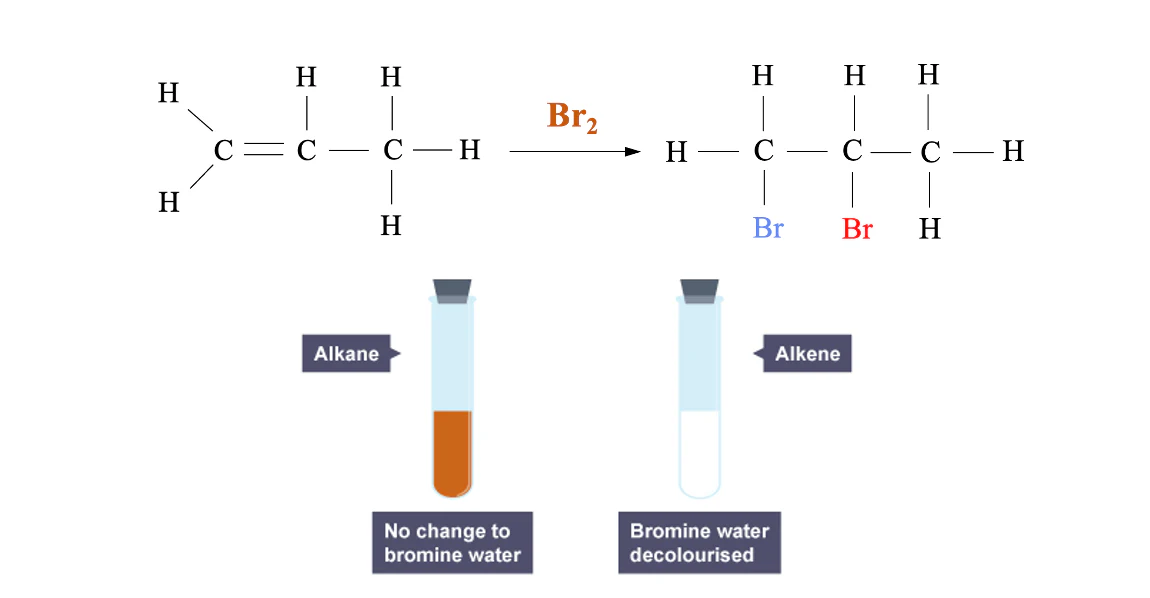

The bromine test exploits the electrophilic addition reaction between bromine and the C=C bond. Students must be able to recognise the resulting loss of colour, an essential visual indicator.

Why Bromine Water Works

Bromine water is orange because of dissolved Br₂. When an alkene is present, bromine adds across the double bond, forming a colourless dibromoalkane. The absence of any other strong competing reactions makes this test highly selective for unsaturation.

Procedure for Detecting Alkenes

The decolourisation of bromine water occurs rapidly at room temperature and does not require catalysts or UV light. Key procedural points include:

Add a small volume of bromine water to the sample.

Shake gently and observe the colour change.

Rapid decolourisation indicates the presence of an alkene.

If no alkene is present, the orange colour persists.

A positive test for an alkene is the rapid decolourisation of bromine water from orange/brown to colourless, showing a C=C bond is present.

Bromine water remains orange with an alkane but is rapidly decolourised by an alkene as bromine adds across the C=C bond, removing Br₂ from solution. Source

The test does not provide structural details, only confirmation of a C=C bond.

Haloalkanes: Hydrolysis and Precipitate Formation

Haloalkanes undergo nucleophilic substitution, yielding alcohols and halide ions. The specification states that haloalkanes should be identified using aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol. This method relies on precipitation of silver halides, each with a distinct colour.

Nucleophile: A species that donates an electron pair and attacks electron-deficient centres.

A sentence is required here to ensure appropriate spacing. Hydrolysis frees halide ions, which then react with silver ions to form insoluble salts.

Why Ethanol Is Used

Ethanol acts as a co-solvent, allowing the haloalkane (organic) and aqueous reagents (inorganic) to mix uniformly. Without ethanol, the reactants would form two layers and hydrolysis would be significantly slower.

Procedure for Identifying Haloalkanes

Students must know the essential steps and the meaning of the observed precipitates. The following points outline the process:

Warm the sample with aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol.

Hydrolysis releases halide ions: Cl⁻, Br⁻, or I⁻.

These ions react with Ag⁺ to form precipitates:

AgCl — white

AgBr — cream

AgI — yellow

The precipitate forms more rapidly for iodoalkanes than for bromo- or chloroalkanes due to weakening of the C–X bond down the group.

Haloalkanes can be identified by warming with aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol; hydrolysis releases halide ions that form a silver halide precipitate (AgCl white, AgBr cream, AgI yellow).

Silver halide precipitates form when halide ions react with aqueous silver nitrate, producing visible cloudiness or solids that confirm the presence of a haloalkane after hydrolysis. Source

Bond Strength and Its Influence on Test Outcomes

The C–X bond strength decreases from C–Cl to C–I. Because hydrolysis requires bond cleavage, the reaction rate follows:

Fastest hydrolysis: iodoalkanes

Intermediate: bromoalkanes

Slowest: chloroalkanes

These differences allow comparison of relative reaction rates, which can help confirm the identity of an unknown haloalkane.

Silver Halide Precipitate Characteristics

Although the specification focuses on identification, understanding the nature of these precipitates supports clearer interpretation:

AgCl dissolves in dilute ammonia, confirming chloride ions.

AgBr dissolves in concentrated ammonia, confirming bromide ions.

AgI does not dissolve in ammonia, confirming iodide ions.

These solubility patterns help validate qualitative observations when colours appear ambiguous.

Key Chemical Principles Underpinning the Tests

Both reactions hinge on interaction between electron-rich and electron-poor centres:

In alkenes, the π-bond provides electron density for electrophilic attack.

In haloalkanes, the polar C–X bond allows nucleophilic substitution during hydrolysis.

Hydrolysis of Haloalkanes (General)

RX + H₂O → ROH + X⁻

RX = haloalkane (R = alkyl group; X = halogen)

ROH = alcohol formed

X⁻ = halide ion detected

A sentence after the equation is required here. This general reaction represents the essential chemical step allowing identification of the halide ion.

Practical Considerations and Good Analytical Technique

Reliable qualitative analysis requires careful attention to experimental conditions:

Control of Temperature

Warming accelerates hydrolysis without causing side reactions. Excessive heating, however, may degrade the haloalkane or alter precipitate appearance.

Avoiding False Positives

Samples must be free from inorganic halide contamination.

Glassware should be rinsed thoroughly.

Ethanol volume should be sufficient to ensure homogeneous mixing.

Observation Skills

Students should be familiar with terms such as:

Decolourisation — loss of bromine colour in alkenes.

Precipitate formation — appearance of solid silver halide.

Reaction rate comparison — evaluating the time taken for cloudiness to appear.

These interpretative skills are essential for correct qualitative analysis in accordance with the specification.

Bringing Together the Two Qualitative Tests

Although they address different functional groups, both tests require students to observe visible changes that correlate directly with underlying chemical behaviour. The bromine test detects unsaturation, while the silver nitrate test identifies the halogen present in a haloalkane and provides further insight through reaction rate differences.

FAQ

Bromine water only confirms the presence of a C=C double bond, not its position or surrounding structure. Different alkenes all undergo electrophilic addition with bromine, leading to the same visual outcome: decolourisation.

Subtle structural features such as branching or substitution do not significantly alter the visual result. As a result, bromine water cannot differentiate between isomers or determine whether an alkene is terminal or internal.

More detailed structural identification requires spectroscopic techniques rather than test-tube reactions.

Yes, in rare cases. Some non-alkene compounds can also decolourise bromine water.

Examples include:

Phenols, which react via electrophilic substitution

Strong reducing agents, which can reduce bromine to bromide

These reactions usually differ in speed or conditions, but visually they may appear similar. This is why bromine water is best used alongside other tests rather than as sole evidence.

Haloalkanes are relatively unreactive towards water at room temperature. Warming provides energy to help break the C–X bond during hydrolysis.

Without heating:

Hydrolysis may be extremely slow

No precipitate may form within a practical timeframe

Gentle warming speeds up ion formation without introducing side reactions, allowing meaningful comparison of reaction rates between different haloalkanes.

The test relies on both aqueous chemistry and organic solubility. Ethanol is used because it:

Dissolves haloalkanes

Mixes with water, unlike many organic solvents

Does not interfere with silver ions

Using only water would create two immiscible layers, slowing hydrolysis. Using non-polar solvents would prevent effective contact between reactants, making the test unreliable.

Precipitate colour identifies the halogen, but reaction rate provides additional confirmation. Faster precipitate formation indicates a weaker C–X bond.

This allows:

Confirmation of halogen identity

Cross-checking when colours are faint or ambiguous

Increased confidence when analysing unknown samples

Rate observations are therefore a valuable qualitative tool alongside precipitate colour, even though no measurements are required.

Practice Questions

A student adds bromine water to an unknown organic liquid and gently shakes the mixture. The bromine water rapidly changes from orange to colourless.

Explain what this observation shows about the structure of the organic liquid.

(2 marks)

States that the organic liquid contains a C=C double bond / is an alkene. (1 mark)

Explains that bromine reacts with the double bond, causing decolourisation of bromine water. (1 mark)

A student is given three unlabelled haloalkanes: A, B and C. Each is warmed separately with aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol.

The following observations are made:

A produces a yellow precipitate almost immediately.

B produces a cream precipitate after about one minute.

C produces a white precipitate after several minutes.

(a) Identify the halogen present in each haloalkane.

(b) Explain the differences in the time taken for the precipitates to form.

(5 marks)

(a) Identification of halogens (3 marks total)

A is an iodoalkane (yellow AgI precipitate). (1 mark)

B is a bromoalkane (cream AgBr precipitate). (1 mark)

C is a chloroalkane (white AgCl precipitate). (1 mark)

(b) Explanation of reaction rate differences (2 marks total)

States that C–X bond strength decreases from C–Cl to C–I. (1 mark)

Explains that weaker C–X bonds hydrolyse faster, releasing halide ions more quickly. (1 mark)