OCR Specification focus:

‘Predict carbon-13 or proton NMR spectra for given molecules studied in the course.’

Introduction

Predicting carbon-13 and proton NMR spectra is essential for understanding how molecular structure determines the number, type, and behaviour of chemical environments. These notes explain how to anticipate key NMR features using structural reasoning.

Predicting NMR Spectra

Accurate prediction of NMR spectra requires understanding how different atoms and functional groups influence chemical shift, integration, and splitting patterns. OCR expects students to predict both ¹³C NMR and ¹H NMR spectra for molecules studied in the course by analysing the number of environments and the expected chemical-shift regions.

Key Principles in NMR Prediction

When predicting spectra, the central questions are:

How many unique chemical environments are present?

What chemical-shift region will each environment appear in?

What will the relative intensity (integration) be?

For ¹H NMR, how will neighbouring protons influence spin–spin splitting?

Before applying these principles, students must understand the term chemical environment.

Chemical environment: The distinct electronic surroundings of a nucleus, leading to a unique NMR signal when not chemically or symmetrically identical to others.

Normal sentences separate definition blocks to maintain clarity and flow.

Predicting ¹³C NMR Spectra

¹³C NMR spectra show a separate peak for each carbon environment, without splitting under standard proton-decoupled conditions. This makes carbon spectra relatively straightforward to predict.

Determining the Number of Carbon Environments

The first step is identifying how many carbons are chemically distinct.

To do this, consider:

The presence of symmetry elements in the molecule

Whether carbons are attached to different atoms or groups

Changes in hybridisation (e.g., sp³, sp², sp)

Anticipating ¹³C Chemical Shift Regions

Carbon environments can be associated with broad chemical-shift regions:

0–50 ppm: saturated sp³ carbons not bonded to electronegative atoms

50–100 ppm: sp³ carbons bonded to heteroatoms, alkynes

100–160 ppm: alkenes and aromatic carbons

160–220 ppm: carbonyl carbons (C=O)

Chemical shifts vary with electronegativity and conjugation. For example, carbons attached to oxygen shift further downfield.

Predicting ¹H NMR Spectra

¹H NMR spectra provide richer detail because protons exhibit chemical shift, integration, and splitting through interaction with neighbouring protons.

Identifying Proton Environments

As with carbons, the number of proton environments depends on molecular symmetry and connectivity. Equivalent protons produce one signal.

Predicting ¹H Chemical Shifts

The predicted shifts depend on functional groups:

0.5–2.0 ppm: alkyl protons

2.0–3.0 ppm: protons adjacent to electronegative atoms

4.0–6.0 ppm: protons on double bonds (alkenes)

6.0–9.0 ppm: aromatic protons

9.0–10.0 ppm: aldehydic protons

These ranges should be used as guidance when predicting spectra. Highly electronegative substituents shift signals downfield because they withdraw electron density.

Integration and Proton Ratios

¹H integration indicates the relative number of protons contributing to each signal.

It is essential for determining structural fragments and must correlate with proton counts predicted from the molecular formula.

Integration (NMR): A measure of the relative area under an NMR signal corresponding to the number of equivalent protons contributing to that environment.

A normal sentence ensures the spacing rule between definitions.

Predicting Splitting Patterns

The n + 1 rule states that a proton with n equivalent neighbouring protons splits into n + 1 peaks. Splitting only occurs between protons on adjacent carbon atoms unless restricted by structural factors.

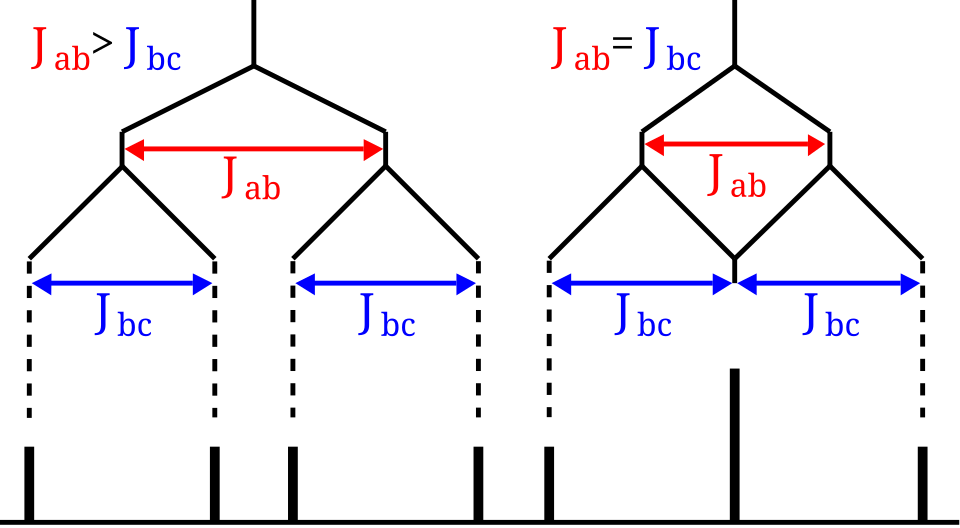

This splitting tree shows how spin–spin coupling produces characteristic multiplets and intensity ratios such as 1:2:1. The left-hand example includes a doublet of doublets, which extends beyond simple n + 1 cases but remains useful for prediction. Source

Key points:

Singlet: no neighbouring protons

Doublet: 1 neighbour

Triplet: 2 neighbours

Quartet: 3 neighbours

Larger multiplets indicate several non-equivalent neighbours

Coupling does not occur when protons exchange rapidly (e.g., O–H or N–H in the presence of acid or moisture).

Combining Predictive Elements

When producing a predicted spectrum for a molecule studied in the course, combine all three elements:

Number of environments (unique carbons or protons)

Expected shift range (functional group influence)

Intensity or splitting (¹H only)

Each peak in a predicted spectrum represents one distinct ¹H or ¹³C environment, so the first step is always to count chemically different nuclei (using symmetry where possible).

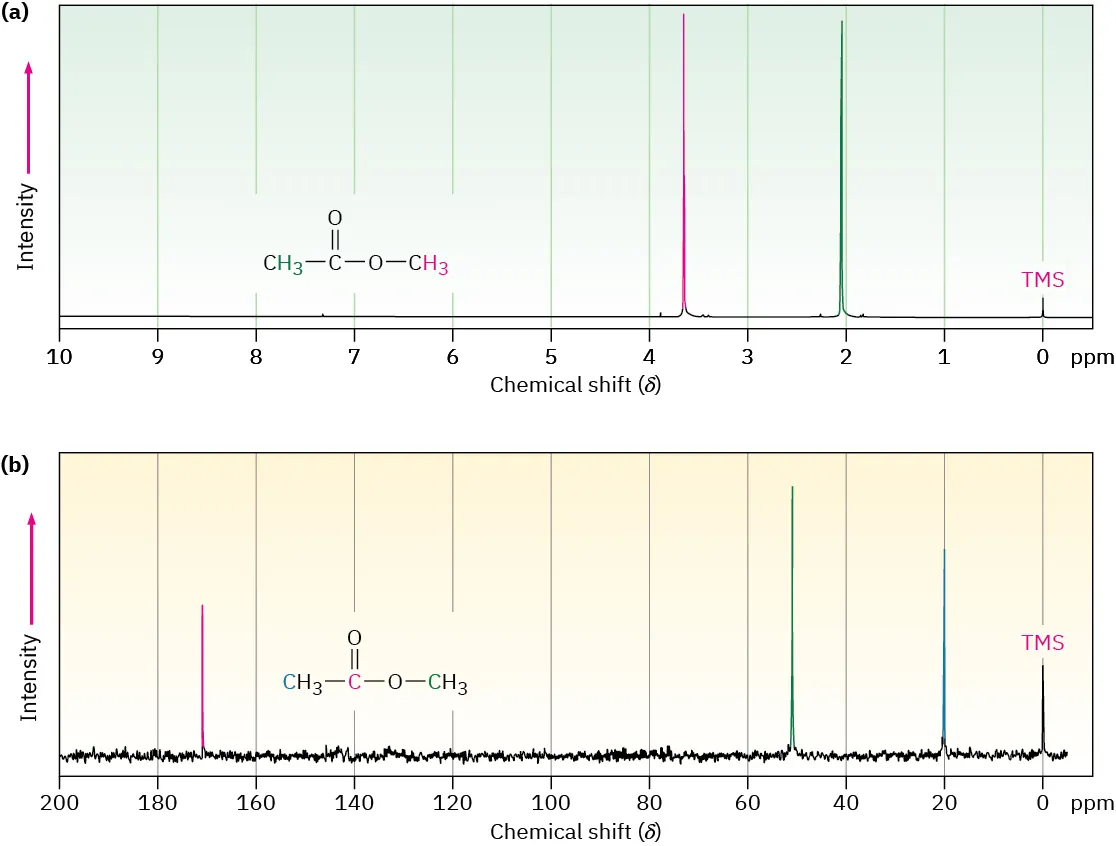

This paired spectrum compares ¹H and proton-decoupled ¹³C NMR for the same molecule, illustrating how proton equivalence reduces the number of signals while each carbon environment gives a separate peak. Source

Structural Features that Influence NMR Predictions

Consider the following influences during prediction:

Electronegative atoms

Withdraw electron density, pushing signals downfield

Broaden shift ranges for both ¹³C and ¹H

Hybridisation

sp² carbons resonate further downfield than sp³

Aromaticity

Ring currents generate characteristic downfield shifts

Conjugation

Delocalisation alters electron density and shifts

Symmetry

Limits the number of distinct environments

Functional groups

Carbonyls, alcohols, amines, and aromatic rings each cause predictable shifts

Predicting Spectra for Molecules Studied in the Course

This subsubtopic requires students to “predict carbon-13 or proton NMR spectra for given molecules studied in the course,” meaning students must justify:

How many NMR signals are expected

Where those signals are likely to appear

How intensity or splitting patterns arise

How functional groups modify expected values

After assigning approximate chemical shift regions, add the expected multiplicity for each proton environment and check that the integration ratio matches the proton counts.

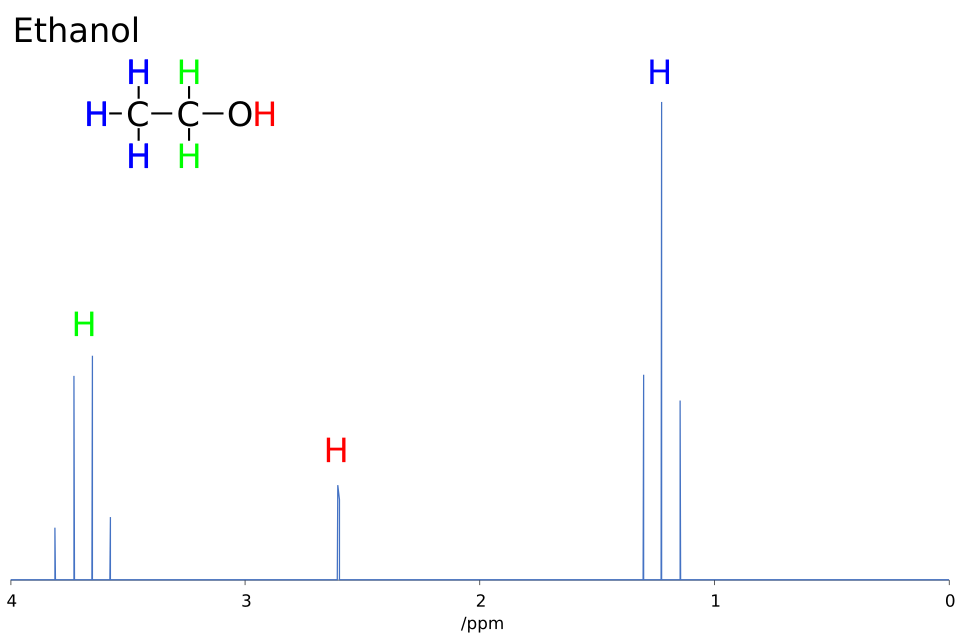

This labelled ¹H NMR spectrum of ethanol shows distinct proton environments, their chemical shifts, and the resulting splitting patterns. Expanded regions highlight how neighbouring protons generate triplet and quartet signals. Source

Bullet-Point Approach to Prediction

Students can summarise prediction reasoning as:

Identify functional groups

Locate symmetry elements

Count unique ¹³C and ¹H environments

Estimate chemical-shift ranges

Determine ¹H integration ratios

Use the n + 1 rule to predict splitting

This structured approach aligns closely with OCR expectations and ensures that predicted spectra are logical, justified, and based on fundamental NMR principles.

FAQ

Predicted chemical shifts are based on typical ranges, not exact values. Real spectra are influenced by subtle electronic effects.

Factors that can cause small differences include:

Nearby electronegative groups altering electron density

Conjugation or resonance effects

Solvent interactions

Magnetic anisotropy from aromatic rings

As a result, predicted values should be treated as approximate rather than precise.

Symmetry reduces the number of unique chemical environments in a molecule.

If atoms can be exchanged by rotation or reflection without changing the molecule, they are equivalent and give one signal.

This is particularly helpful when predicting spectra quickly, as recognising symmetry can immediately limit the number of expected peaks in both ¹H and ¹³C NMR.

Signal broadening often occurs when protons exchange rapidly or interact with neighbouring heteroatoms.

Common causes include:

O–H or N–H protons undergoing hydrogen bonding

Proton exchange with trace water or acid

Overlapping signals from similar environments

Although broadening is not always predictable in detail, students should expect exchangeable protons to appear less sharp.

Yes, particularly for simple molecules with few functional groups.

Structural isomers may share the same number of environments, similar chemical shifts, and identical splitting patterns.

This is why predicted NMR spectra are often used alongside other data, such as molecular formula or functional group tests, to confirm structures rather than identify them alone.

Coupling may be absent if protons exchange rapidly or if the coupling pathway is disrupted.

This can occur when:

Protons are attached to oxygen or nitrogen

Rapid proton exchange averages out splitting

Neighbouring protons are equivalent

Understanding these limitations helps explain why predicted splitting patterns may occasionally simplify in real spectra.

Practice Questions

A compound has the molecular formula C4H10O and contains no C=C bonds.

Predict the number of signals expected in its proton (¹H) NMR spectrum, stating one structural feature that justifies your answer.

(2 marks)

1 mark

Correct prediction of three proton environments / three ¹H NMR signals.

1 mark

Valid structural justification, such as:

Presence of equivalent methyl protons

Symmetry in the alkyl chain

Different environments for CH3, CH2 and O–H protons

Propanal, CH3CH2CHO, is one of the molecules studied in the course.

(a) Predict the number of signals expected in the proton (¹H) NMR spectrum of propanal.

(b) State the expected chemical-shift region for each signal.

(c) Predict the splitting pattern for each signal.

(5 marks)

(a) Number of signals (1 mark)

1 mark

Correct answer: three proton environments / three ¹H NMR signals.

(b) Chemical shift regions (2 marks)

1 mark

Aldehyde proton correctly identified at approximately 9–10 ppm.

1 mark

Alkyl protons correctly identified:

CH2 next to C=O at approximately 2–3 ppm

CH3 at approximately 0.5–1.5 ppm

(Allow credit if both alkyl regions are correctly described together.)

(c) Splitting patterns (2 marks)

1 mark

Aldehyde proton predicted as a triplet due to coupling with adjacent CH2 protons.

1 mark

Correct splitting of alkyl protons:

CH2 as a quartet (neighbouring CH3 protons)

CH3 as a triplet (neighbouring CH2 protons)

(Allow full credit if splitting patterns are correctly assigned but order is reversed.)