OCR Specification focus:

‘Predict number and types of carbon environments from chemical shifts; propose possible structures.’

Introduction

Carbon-13 NMR spectroscopy reveals the number and types of carbon environments in an organic molecule, allowing structural features to be deduced through characteristic chemical shift patterns.

Understanding Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy

What Carbon-13 NMR Measures

Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (¹³C NMR) detects how carbon nuclei absorb radiofrequency energy when placed in a magnetic field. Only the ¹³C isotope, which is naturally low in abundance, is NMR-active. Its low abundance eliminates most carbon–carbon coupling, giving simplified spectra, which is advantageous for qualitative structural analysis.

Carbon Environments in ¹³C NMR

A carbon environment refers to a set of carbon atoms in identical chemical surroundings.

Carbon Environment: A carbon atom or group of carbon atoms that share the same connectivity and spatial arrangement, producing a single unique signal in a ¹³C NMR spectrum.

The number of carbon environments corresponds directly to the number of distinct peaks in a ¹³C NMR spectrum. This relationship forms the basis of structural predictions required by the OCR specification.

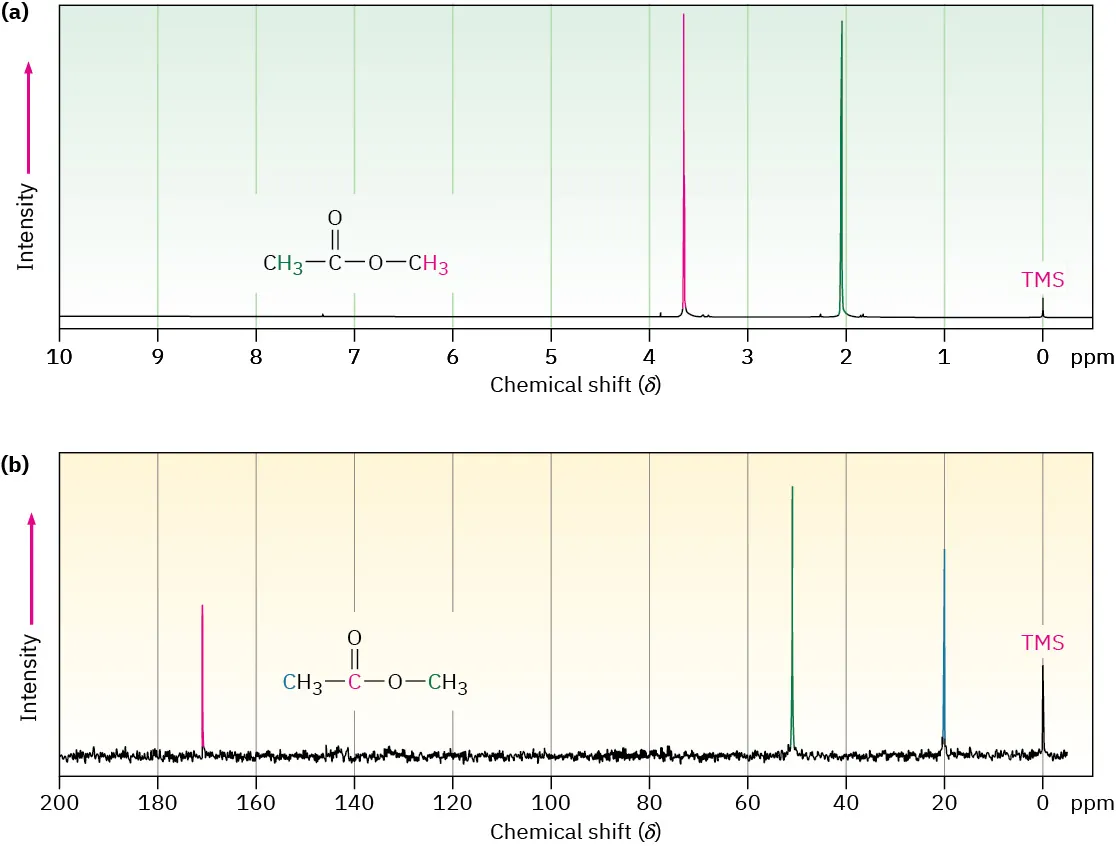

This figure compares a proton NMR spectrum with a proton-decoupled ¹³C NMR spectrum of the same compound, showing that each chemically distinct carbon environment gives a single signal. The TMS peak at 0 ppm provides the reference point for chemical shift measurements. Source

Different molecular symmetries can reduce the total number of observed environments. For example, two carbons related by symmetry appear as a single signal. Students must therefore consider molecular symmetry carefully when using ¹³C NMR to infer structures.

Chemical Shifts in Carbon-13 Spectra

Chemical shift values indicate the electronic environment surrounding each carbon atom. They are measured in parts per million (ppm) relative to the standard tetramethylsilane (TMS). Electronegative atoms, π-systems and hybridisation states alter electron density around carbon nuclei, producing characteristic ranges of chemical shifts.

Chemical Shift: The resonance position of a nucleus relative to a standard reference compound, influenced by its surrounding electron density, measured in ppm.

After understanding the meaning of chemical shifts, it becomes easier to apply the specification requirement of using them to identify different types of carbon environments.

Key Factors Affecting Chemical Shifts

Several structural features systematically influence chemical shift values:

Hybridisation:

sp³ carbons in alkanes appear upfield (0–50 ppm).

sp² carbons of alkenes and aromatic rings appear downfield (100–160 ppm).

sp carbons show signals typically around 70–90 ppm.

Electronegative atoms:

Atoms such as oxygen, halogens and nitrogen withdraw electron density, shifting carbon signals downfield (to higher ppm).π-Systems:

Carbonyls, C=C, and aromatic systems deshield attached carbons, causing significant downfield shifts.Substitution pattern:

Increased branching or substitution alters charge distribution and may shift signals slightly upfield or downfield.

These trends are essential when predicting the type of carbon environment associated with each signal.

Interpreting Carbon-13 Spectra

Counting Carbon Environments

The first step in interpreting a ¹³C NMR spectrum is counting the number of peaks, each representing one unique carbon environment. Students must match this number with possible molecular structures to narrow down structural options. Since OCR emphasises prediction of structures from carbon environments, this forms a core skill.

Assessing the Type of Carbon from Chemical Shift Ranges

Chemical shift ranges allow identification of functional groups through characteristic values. Key ranges include:

0–50 ppm: Alkanes and simple saturated carbons.

50–90 ppm: Carbons attached to electronegative atoms or sp carbons.

100–160 ppm: Aromatic and alkene carbons.

160–220 ppm: Carbonyl carbons (aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, esters).

Use the chemical shift to classify each signal as alkyl, C–O, C=C/aromatic, or C=O carbon before proposing structures.

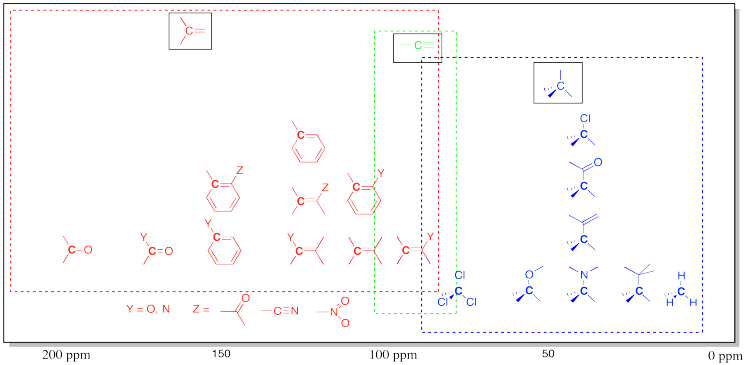

This diagram summarises typical ¹³C chemical shift regions across the spectrum, linking ppm ranges to common types of carbon environments. It visually highlights why carbonyl carbons appear far downfield and alkyl carbons appear upfield. Source

These ranges help distinguish between functional groups and predict structural fragments.

Using Splitting: Why ¹³C Spectra Usually Lack Spin–Spin Coupling

Routine ¹³C NMR spectra are acquired with proton decoupling, meaning that ¹H–¹³C spin–spin coupling is removed. This produces sharper, singlet peaks, making it easier to count carbon environments without interpreting complex splitting patterns. Although coupling information can be obtained using specialised techniques, it is not required by the OCR specification for this subsubtopic.

Integration in Carbon-13 NMR

Unlike proton NMR, ¹³C NMR signals are generally not integrated because signal intensities do not reliably correlate with the number of carbons. Differences in relaxation times, nuclear Overhauser effects, and low natural abundance weaken the usefulness of integration. Students should therefore focus primarily on peak number and chemical shift when applying ¹³C NMR for structural deduction.

Applying ¹³C NMR to Propose Structures

Linking Chemical Shifts to Structural Features

To meet the specification requirement of proposing structures, students must combine:

Number of carbon environments

Types of carbons indicated by chemical shift

Functional-group-specific ranges

Symmetry of the molecule

This combination allows narrowing down possible structures and identifying functional groups confidently.

Guided Approach for Structural Prediction

The following process supports accurate interpretation aligned with OCR expectations:

Step 1: Count the peaks to determine the number of carbon environments.

Step 2: Compare each chemical shift with characteristic ranges to identify possible carbon types.

Step 3: Consider symmetry to account for reduced numbers of observed environments.

Step 4: Assemble structural fragments from the identified carbon types.

Step 5: Compare proposed structures with the spectral pattern and eliminate incompatible options.

This multi-layered approach directly reflects the OCR demand to predict the number and type of carbon environments and propose viable structures.

Carbonyl and Aromatic Indicators

Certain functional groups produce highly characteristic signals:

Carbonyl carbons (C=O) appear strongly downfield due to intense deshielding, often between 160–220 ppm.

Aromatic carbons appear between 110–160 ppm, forming clustered signals reflecting the ring environment.

These features are powerful structural markers and frequently form the starting point of structure identification.

Recognising Equivalent Carbons

A final consideration is molecular symmetry. Equivalent carbons reduce the number of expected environments, and failure to recognise this can lead to incorrect structural proposals. If several carbons are chemically equivalent (often due to symmetry), they produce one 13C signal at the same chemical shift.

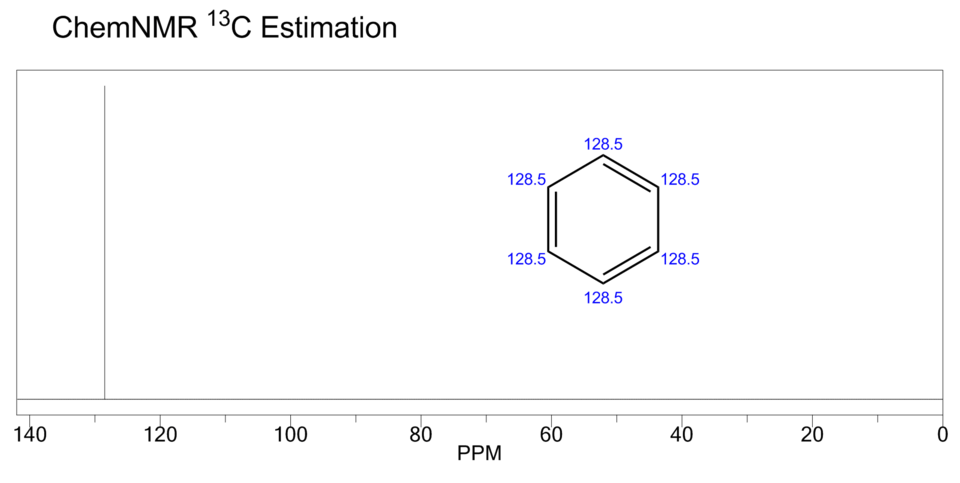

This ¹³C NMR spectrum of benzene shows a single signal because all six carbons are chemically equivalent. It illustrates how molecular symmetry reduces the number of observed carbon environments despite multiple carbon atoms being present. Source

For example, symmetrical alicyclic compounds or molecules with identical substituents frequently show fewer peaks than their molecular formula might suggest.

Understanding these nuances ensures accurate interpretation fully aligned with the specification requirement to predict carbon environments and propose plausible structures.

FAQ

Carbonyl carbons are strongly deshielded because the C=O bond contains a highly polarised π-system. Oxygen withdraws electron density from the carbon nucleus, exposing it more directly to the external magnetic field.

The π-electrons also create local magnetic effects that further increase deshielding. As a result, carbonyl carbons consistently appear far downfield, typically between 160 and 220 ppm, making them easy to identify.

Carbon-13 is much less abundant than hydrogen. Only about 1.1% of carbon atoms are the NMR-active ¹³C isotope.

This low natural abundance means fewer nuclei contribute to the signal, reducing sensitivity. To compensate, spectra are recorded over longer times with repeated scans, which is why ¹³C NMR experiments typically take longer than proton NMR experiments.

Peak intensity in carbon-13 NMR depends on factors beyond the number of carbons present. These include:

Differences in relaxation times between carbons

The nuclear Overhauser effect, which enhances some signals more than others

Variations in local molecular motion

Because of these effects, peak height cannot be used reliably to count carbons, which is why integration is generally not used in carbon-13 NMR.

When a molecule has symmetry, some carbon atoms experience identical chemical environments. These equivalent carbons absorb energy at the same frequency and produce a single signal.

For example, symmetrical aromatic rings or molecules with identical substituents often show fewer signals than the number of carbon atoms in the molecular formula. Recognising symmetry is essential when matching spectra to possible structures.

Carbon nuclei experience a much wider range of electronic environments than hydrogen nuclei. Differences in bonding, hybridisation, and proximity to electronegative atoms affect carbon shielding more dramatically.

As a result, carbon-13 chemical shifts spread across a range of approximately 0–220 ppm, compared with about 0–10 ppm for protons. This wider scale reduces peak overlap and helps distinguish different carbon environments clearly.

Practice Questions

A compound has the molecular formula C4H10O and produces three signals in its proton-decoupled carbon-13 NMR spectrum.

Explain what this indicates about the number and nature of carbon environments in the molecule.

(2 marks)

1 mark

Correctly states that the molecule contains three different carbon environments.

1 mark

Explains that some carbons are chemically equivalent, often due to symmetry or identical chemical surroundings, causing them to produce the same 13C signal.

A proton-decoupled carbon-13 NMR spectrum of an organic compound shows four signals at approximately 20 ppm, 55 ppm, 130 ppm, and 170 ppm.

a) State how many different carbon environments are present in the molecule.

b) For each signal, identify the most likely type of carbon environment.

c) Explain how the information from the carbon-13 NMR spectrum can be used to help propose a possible structure for the compound.

(5 marks)

a) Number of carbon environments (1 mark)

1 mark

States that there are four different carbon environments, corresponding to four signals.

b) Identification of carbon types (3 marks total)

1 mark

20 ppm identified as a saturated alkyl (sp³) carbon.

1 mark

55 ppm identified as a carbon bonded to an electronegative atom, such as C–O.

1 mark

130 ppm and/or 170 ppm correctly identified as unsaturated or carbonyl environments, with:

~130 ppm as alkene or aromatic carbon

~170 ppm as carbonyl (C=O) carbon

c) Use of data to propose a structure (1 mark)

1 mark

Explains that combining the number of carbon environments with chemical shift ranges allows functional groups to be identified and used to narrow down or propose possible molecular structures.

(Answers do not need to give a full structure to gain this mark.)