OCR Specification focus:

‘Carry out titrations using burette and pipette; use a volumetric flask to prepare standard solutions; select suitable acid–base indicators.’

Introduction

Volumetric analysis and solution preparation are essential techniques in analytical chemistry, enabling precise determination of substance concentrations and preparation of accurate standard solutions for quantitative experiments.

Understanding Volumetric Analysis

Volumetric analysis involves quantitative chemical analysis using precise volume measurements to determine unknown concentrations of solutions. It relies on accurately prepared reagents and meticulous technique to achieve reliable data.

Volumetric Analysis: A method used to determine the concentration of a solution by reacting it with a solution of known concentration.

Titrations are the most common form of volumetric analysis, using accurately measured volumes of solutions that react in known stoichiometric ratios.

Essential Apparatus for Volumetric Work

Accurate volumetric analysis requires the correct use of calibrated glassware designed for precision measurements. Key apparatus includes:

Pipette: For delivering a fixed, precise volume of solution (usually 10.0, 25.0, or 50.0 cm³).

Burette: For dispensing variable, measurable volumes of a titrant during a titration.

Volumetric flask: For preparing standard solutions of accurately known concentration.

Conical flask: Used to contain the solution being titrated, allowing efficient mixing without spillage.

Funnel and wash bottle: Used for transferring and rinsing solutions accurately to prevent loss of reagents.

Each item must be clean and free of contaminants, as impurities can alter results by introducing additional reactants or residues.

Use a burette to deliver titrant into a conical flask containing an aliquot measured accurately with a pipette.

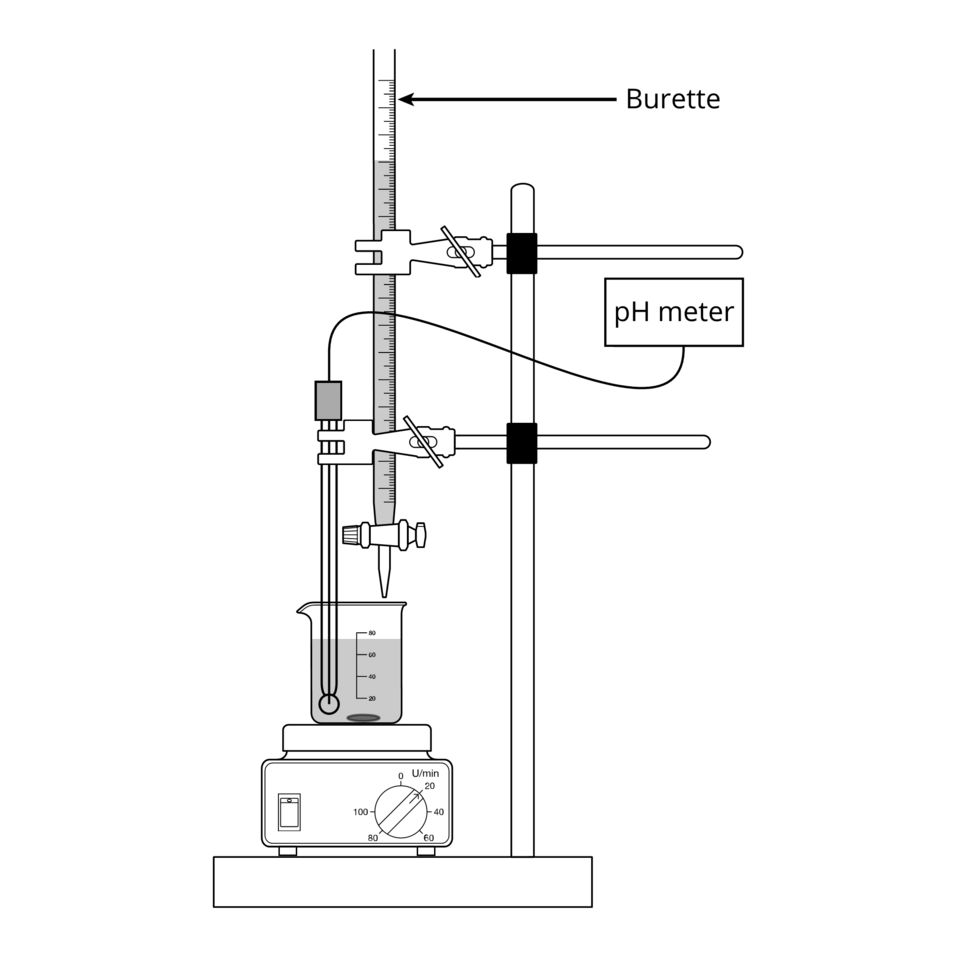

Diagram of a standard acid–base titration: a burette delivering titrant into a conical flask on a support. The figure also shows a pH probe and stir plate, which are optional but commonly used for stable mixing and potentiometric end-point detection. Extra items (probe/stirrer) exceed the OCR minimum but do not alter the core setup. Source

Preparing Standard Solutions

A standard solution is a solution of known concentration, prepared by dissolving an accurately weighed mass of solute in a specific volume of solvent.

Standard Solution: A solution whose concentration is accurately known, often used as a reference in titrations.

Procedure for Preparing a Standard Solution

Weighing the solute

Select a primary standard—a solid that is pure, stable, and has a high molar mass (e.g. anhydrous sodium carbonate, Na₂CO₃).

Accurately weigh the required mass using an analytical balance (±0.001 g).

Dissolving the solute

Transfer the solid into a beaker using a funnel or spatula, rinsing any residue from the weighing vessel.

Add distilled or deionised water and stir until fully dissolved.

Transferring to a volumetric flask

Pour the solution carefully through a funnel into a clean volumetric flask.

Rinse the beaker and funnel into the flask to ensure all solute is transferred.

Diluting to the mark

Add distilled water until the meniscus touches the calibration line on the neck of the flask when viewed at eye level.

Stopper and invert several times to ensure thorough mixing.

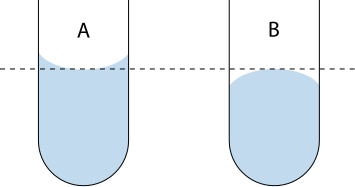

Fill the volumetric flask so the bottom of the meniscus just touches the calibration line at eye level to avoid parallax error.

Clean schematic of correct meniscus reading at eye level. It emphasises aligning the bottom of a concave meniscus with the mark for aqueous solutions. The diagram is uncluttered and ideal for reinforcing good volumetric technique. Source

Accuracy at every stage is crucial, as errors in mass, volume, or temperature directly affect the concentration of the standard solution.

Performing a Titration

A titration measures the exact volume of one solution required to react completely with another. The process provides the data necessary to calculate concentrations through stoichiometric relationships.

Steps in a Titration

Rinse equipment appropriately before use:

Burette with the titrant, pipette with the solution it will deliver, and conical flask with distilled water only.

Fill the burette with the titrant, ensuring no air bubbles remain in the tip.

Pipette a known volume of the solution of unknown concentration into the conical flask, adding a few drops of a suitable acid–base indicator.

Titrate carefully, swirling the flask continuously, until the end point is reached—when the indicator changes colour.

Record the burette reading precisely to two decimal places, estimating to the nearest 0.01 cm³.

Repeat the titration until concordant titres (within 0.10 cm³) are achieved.

Acid–Base Indicators

An indicator is a substance that changes colour at or near the equivalence point of a titration, allowing visual identification of the reaction’s completion.

Acid–Base Indicator: A weak acid or base that exhibits a distinct colour change at a specific pH range.

Choosing an Appropriate Indicator

The indicator must correspond to the pH change at the equivalence point of the titration:

Strong acid vs. strong base: Use phenolphthalein (colourless to pink) or methyl orange (red to yellow).

Strong acid vs. weak base: Methyl orange is suitable.

Weak acid vs. strong base: Phenolphthalein is preferred.

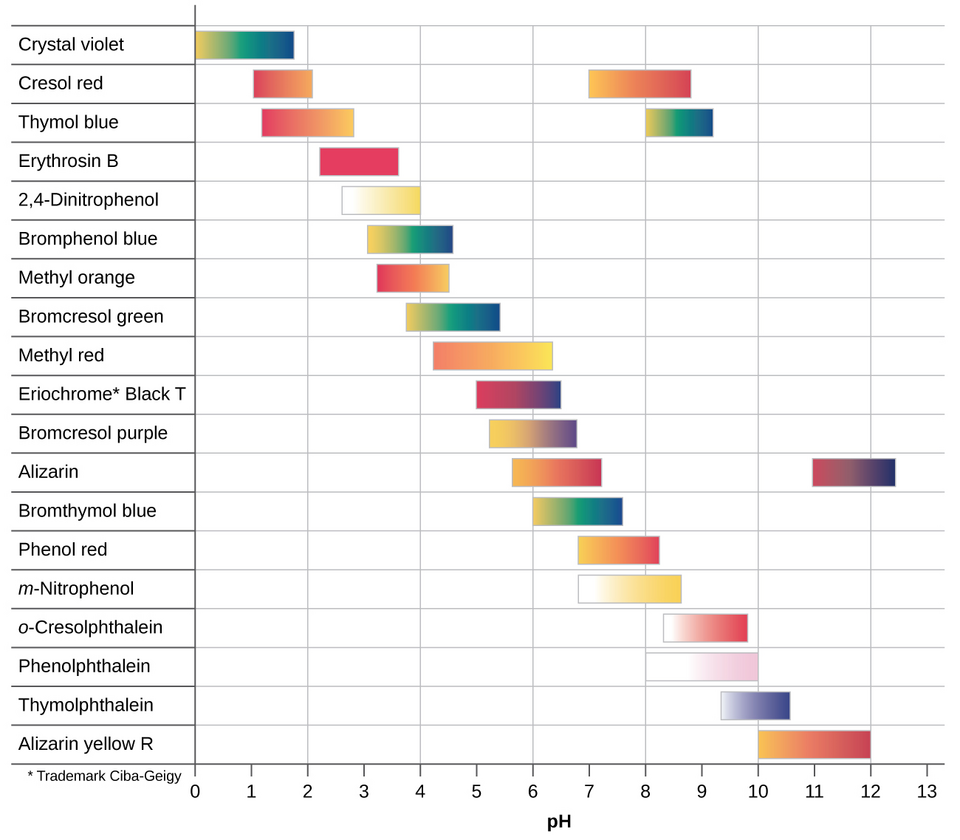

Select an acid–base indicator whose transition range matches the equivalence-point pH (e.g., methyl orange for strong acid–weak base titrations, phenolphthalein for weak acid–strong base).

Chart of common acid–base indicators showing colour changes across transition pH ranges. Use it to justify the choice of methyl orange versus phenolphthalein relative to the expected equivalence pH. Note: the figure includes indicators beyond the OCR essentials. Source

Incorrect indicator choice results in a gradual or misleading colour change, leading to inaccurate titre values.

Common Sources of Error and Minimisation

Achieving reliable volumetric data depends on recognising and reducing errors:

Parallax error: Always read the meniscus at eye level.

Contamination: Ensure all glassware is rinsed appropriately before use.

Temperature effects: Conduct titrations at constant room temperature to prevent density variations.

Inconsistent drop size: Use a consistent technique when operating the burette tap.

Incomplete reactions: Swirl continuously to ensure thorough mixing.

Consistency across multiple titrations helps reduce random errors and improve precision.

Concentration (c) = Moles (n) / Volume (V)

c = concentration (mol dm⁻³)

n = amount of substance (mol)

V = volume of solution (dm³)

This equation underpins all volumetric analysis calculations, connecting measured volumes to chemical quantities.

Maintaining Accuracy and Precision

In volumetric analysis:

Use distilled or deionised water to prevent contamination.

Avoid air bubbles in the burette nozzle or pipette tip.

Record all measurements at a consistent temperature and pressure.

When diluting, always mix thoroughly to produce a uniform concentration.

Precision depends on the repeatability of titres, while accuracy depends on the correct calibration and use of apparatus.

Safety Considerations

Working with chemical solutions requires adherence to good laboratory practice:

Wear safety goggles and a lab coat.

Handle acids and alkalis with care; both can be corrosive.

Rinse spillages immediately with water and report to the supervisor.

Dispose of waste solutions in accordance with local regulations and COSHH guidelines.

Understanding the chemical properties and hazards of all substances used in titrations ensures safe, reliable experimental practice.

FAQ

A primary standard must be pure, stable in air, non-hygroscopic, and have a high molar mass to minimise weighing errors. It should also dissolve readily in water and react completely and stoichiometrically with the titrant.

Common examples include sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) and potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHC8H4O4), both of which are solid, stable, and easy to handle in a laboratory environment.

Rinsing ensures that any residual water or previous solution inside the apparatus does not dilute or contaminate the new solution being used. This maintains concentration accuracy.

Pipette: Rinse with the solution being pipetted (the analyte).

Burette: Rinse with the titrant. Failure to do so can cause systematic errors in titre readings and concentration calculations.

Temperature changes cause liquids to expand or contract, slightly altering their volume. Since volumetric apparatus is calibrated at 20°C, significant deviation affects accuracy.

Higher temperatures: Liquid expands → measured volume is greater than true value.

Lower temperatures: Liquid contracts → measured volume is smaller. This introduces small but important systematic errors in precise titrations.

Swirling ensures that the titrant and analyte mix uniformly, allowing the reaction to proceed evenly throughout the solution.

Without consistent swirling, the local concentration of one reagent may be higher near the burette stream, leading to overshooting the endpoint. Gentle, continuous swirling helps maintain even reaction rates and accurate detection of the colour change.

Reproducibility depends on performing each titration in the same way every time. To achieve consistent results:

Add titrant dropwise near the endpoint.

Use the same indicator concentration and observation angle.

Dry and clean all glassware thoroughly.

Discard anomalous titres and calculate the mean from concordant readings (within 0.10 cm³). Following these steps ensures precision and reliability in volumetric data.

Practice Questions

During a titration, a student accidentally reads the top of the meniscus instead of the bottom when recording the burette readings. Explain how this error affects the calculated concentration of the solution being analysed. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies that reading the top of the meniscus instead of the bottom gives a higher burette reading.

1 mark: States that this makes the calculated concentration of the unknown solution appear lower than it actually is.

A student prepares a standard solution of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) by dissolving 2.65 g of the solid in water and making up the solution to 250 cm³ in a volumetric flask.

(a) Calculate the concentration of the sodium carbonate solution in mol dm⁻³. (3 marks)

(b) State two steps the student should take to ensure the standard solution is prepared accurately. (2 marks)

(5 marks)

(a)

1 mark: Calculates moles of Na2CO3 = 2.65 / 106 = 0.025 mol.

1 mark: Converts volume to dm³ = 250 cm³ = 0.250 dm³.

1 mark: Calculates concentration = 0.025 / 0.250 = 0.10 mol dm⁻³.

(b)

1 mark: States the student should rinse all transferred equipment (e.g. funnel and beaker) into the volumetric flask.

1 mark: States the student should ensure the bottom of the meniscus is at the calibration mark at eye level when filling the flask.