OCR Specification focus:

‘Define anhydrous, hydrated and water of crystallisation; calculate the formula of hydrated salts from composition or experimental data.’

Hydrated salts and their associated water molecules are an essential aspect of chemical formulae and stoichiometric calculations. This topic focuses on how bound water affects chemical composition, structure, and analysis.

Hydrated Salts and the Nature of Water Binding

Hydrated salts are ionic compounds that contain water molecules within their solid crystalline structure. These water molecules are not simply trapped physically but are held in fixed proportions that form part of the compound’s chemical identity. The water content changes the mass, appearance, and some physical properties of the solid. An understanding of the terms connected with hydration is essential for interpreting formulae and determining composition experimentally.

Hydrated salt: An ionic compound that contains water of crystallisation within its solid lattice.

A hydrated compound can often be identified visually because it may appear crystalline or coloured compared with its anhydrous counterpart. Heating a hydrated salt frequently drives off the water, revealing useful information for analytical chemistry.

Anhydrous: A substance that contains no water of crystallisation.

Hydrated copper(II) sulfate, CuSO₄·5H₂O, is a bright blue crystalline solid, whereas anhydrous CuSO₄ is a white powder.

Blue crystals of hydrated copper(II) sulfate, CuSO₄·5H₂O. The vivid blue colour arises because water molecules are part of the crystal lattice as water of crystallisation. This image illustrates what a hydrated salt looks like in practice at A-Level. Source

Hydrated salts commonly lose mass when heated because water molecules leave the structure as vapour. This reversible process is critical to determining the number of water molecules associated with each formula unit of the salt.

Understanding Water of Crystallisation

Water of crystallisation is water chemically incorporated into the crystal lattice of a compound in definite stoichiometric ratios. These water molecules help stabilise the structure via ionic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or coordination to metal ions.

Water of crystallisation: Water molecules that are chemically bound within a crystalline compound in fixed whole-number ratios.

These included water molecules must be represented explicitly when writing formulae. Hydrated salts use the notation “·xH₂O”, in which x is the number of moles of water per mole of compound. Determining the value of x experimentally is one of the main skills required for this subsubtopic.

In a hydrate, water molecules occupy fixed positions within the ionic lattice and are present in a definite whole-number ratio to the anhydrous ions.

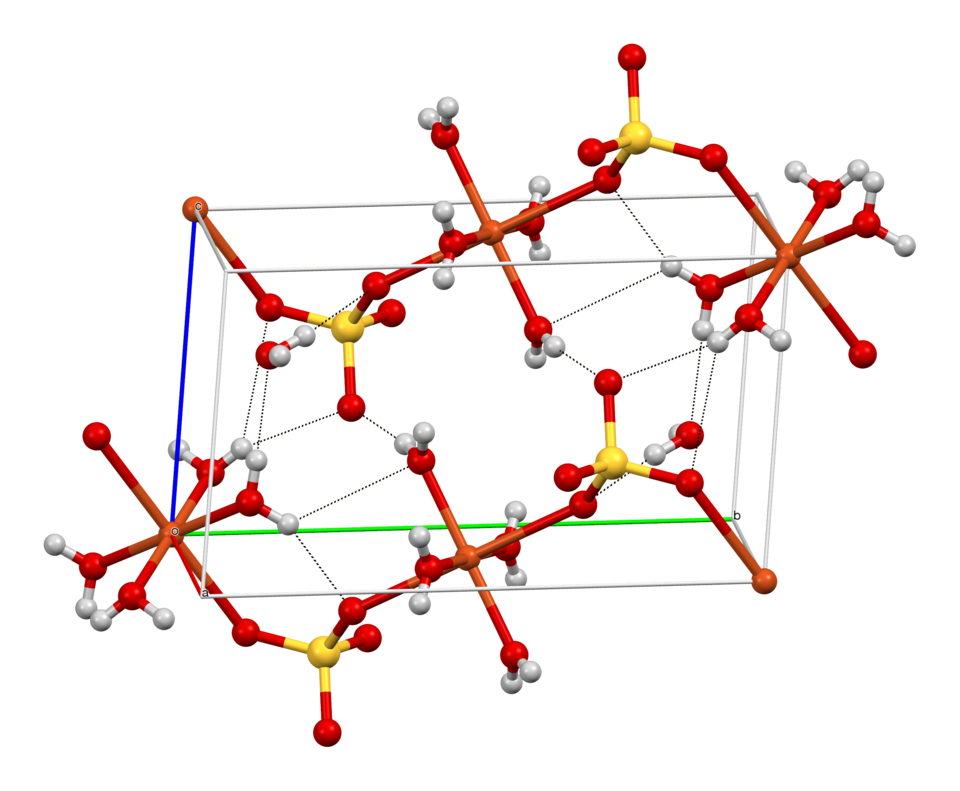

Ball-and-stick model of the crystal structure of CuSO₄·5H₂O, showing copper ions, sulfate ions and water molecules. This visual emphasises that water molecules are chemically bound within the lattice. The dashed hydrogen bonds and detailed geometry exceed OCR expectations but reinforce the ordered hydrated structure. Source

Hydrated ionic lattices often exhibit distinct colours or textures, providing qualitative evidence of hydration. For example, removing water may cause the structure to collapse slightly, resulting in a powdery and paler anhydrous solid. Such observations serve as useful reinforcement of the underlying structural chemistry.

Formulae of Hydrated Salts

The key analytical task is to determine the formula of a hydrated salt using composition or experimental mass data. Such calculations rely on interpreting changes in mass due to the controlled removal of water. The procedure requires careful heating, cooling, and weighing, always ensuring that the salt is fully dehydrated without overheating or decomposing.

Key Features of Hydrated Salt Formulae

The formula always includes the base ionic compound, e.g., CuSO₄.

The number of water molecules is shown after a centred dot: e.g., CuSO₄·5H₂O.

The value of x must always be a whole number, reflecting fixed stoichiometric ratios.

The mass contribution of water is essential when determining molar quantities.

When analysing data to find x, the chemist compares the moles of anhydrous salt with the moles of water removed. Although calculations are not included here, the conceptual foundation is essential to understand how hydration numbers are determined.

Experimental Determination of Water of Crystallisation

The dehydration of a hydrated salt is central to quantifying its water content. Heating causes the bound water to be released as steam, and careful mass measurements before and after heating allow the number of water molecules to be deduced.

General Process Overview

Weigh a sample of the hydrated salt accurately.

Heat gently to remove loosely bound surface moisture first.

Increase heat to drive off the chemically bound water of crystallisation.

Cool the sample in a desiccator to avoid reabsorption of moisture.

Reweigh to determine the mass of anhydrous salt.

Use mass differences to work out the ratio of moles of water to moles of salt.

In the laboratory, the value of x in CuSO₄·xH₂O can be found by heating a known mass of hydrated salt in a crucible to constant mass.

A crucible heated over a laboratory burner on a triangle support, as used to drive off water of crystallisation when determining hydration number. This setup demonstrates heating to constant mass before weighing. The burner position and additional apparatus details extend slightly beyond OCR requirements but support the practical context. Source

Between heatings, the sample must be cooled before weighing to prevent convection currents from affecting the balance reading. Reheating and reweighing may be needed until a constant mass is achieved, ensuring complete removal of water.

Important Considerations in Practical Work

Some hydrated salts decompose on heating instead of forming clean anhydrous solids, so chemical knowledge is required to judge suitability.

Overheating may drive off more than water, creating inaccurate results.

Many anhydrous salts are hygroscopic, so exposure to air must be minimised after heating.

All calculated values assume full dehydration is achieved; incomplete heating leads to underestimation of x.

Structural Significance of Water of Crystallisation

The inclusion of water molecules influences the physical and chemical behaviour of many salts. These water molecules may coordinate directly to metal ions in transition-metal salts, stabilising characteristic colours or affecting solubility. In other compounds, water may help generate extended hydrogen-bonded networks that maintain the integrity of the lattice.

Hydrated structures can exhibit changes in density, melting point, and crystalline form compared with the anhydrous version. Although these properties are not always assessed explicitly in the OCR specification, recognising their origin helps reinforce the connection between observed behaviour and the underlying lattice structure.

Practical Importance of Hydrated Salts

Hydrated salts are widely used in laboratories and industry. Their known water content allows chemists to prepare solutions accurately, provided the hydration state is accounted for when calculating required masses. Misidentifying whether a salt is hydrated or anhydrous can lead to significant quantitative errors, especially in analytical work, stoichiometric reactions, and standard solution preparation.

Hydrated salts appear in drying agents, reagents, catalysts, and qualitative analysis.

Accurate determination of hydration number is essential when assessing purity.

The controlled removal or incorporation of water is a valuable tool in materials synthesis.

Understanding the relationship between composition, structure, and water content forms a crucial foundation for further topics in chemical formulae and stoichiometry.

FAQ

The water of crystallisation helps maintain the three-dimensional lattice, affecting density, hardness, and shape. Removing this water often collapses the lattice, making the solid more powdery or brittle.

In some transition-metal hydrates, coordinated water influences d-orbital splitting, which in turn affects observed colour. Differences in hydration states therefore produce distinct visual and physical changes.

Some salts decompose before all water of crystallisation can be removed. This occurs when the removal of water destabilises the ionic lattice or leads to oxidation or reduction of the ions present.

Salts containing easily oxidised metal ions, or polyatomic anions such as carbonates, may break down instead of dehydrating neatly.

A hot crucible generates convection currents that interfere with balance readings. Allowing the sample to cool ensures accurate mass measurements.

Cooling in a desiccator also prevents hygroscopic anhydrous salts from reabsorbing moisture, which would distort mass values.

Hydration strength depends on:

Charge density of the metal ion

Ability of the water molecules to coordinate directly to the metal

Extent of hydrogen bonding within the lattice

Higher charge density cations (e.g., Mg2+, Al3+) typically bind water more strongly, making dehydration more energy-demanding.

Rapid heating can spatter the sample or cause partial decomposition by exposing the salt to temperatures far above those needed for dehydration.

Gentle, stepwise heating lets surface moisture evaporate first, then allows chemically bound water to leave without damaging the structure of the remaining solid.

Practice Questions

A blue crystalline solid is heated strongly and becomes a white powder.

(a) State the terms used to describe the original blue solid and the white solid formed.

(b) Explain why the colour change occurs.

(2 marks)

(a)

Hydrated (blue solid) AND anhydrous (white solid). (1)

(b)

Water of crystallisation is lost on heating, causing the colour change. (1)

A student heats 3.12 g of a hydrated salt, MX·xH2O, until a constant mass is reached. After heating, the mass of the anhydrous salt is 1.92 g.

(a) Calculate the mass of water lost.

(b) Calculate the number of moles of water removed.

(c) Calculate the number of moles of anhydrous MX formed.

(d) Determine the value of x in MX·xH2O.

(The molar mass of MX = 120 g mol–1; molar mass of H2O = 18 g mol–1.)

(5 marks)

(a)

Mass of water lost = 3.12 − 1.92 = 1.20 g. (1)

(b)

Moles of water = 1.20 / 18 = 0.0667 mol. (1)

(c)

Moles of anhydrous MX = 1.92 / 120 = 0.0160 mol. (1)

(d)

Ratio x = moles of water / moles of MX = 0.0667 / 0.0160 ≈ 4.17 → x = 4. (1)

Correct final formula MX·4H2O. (1)