OCR Specification focus:

‘Define electronegativity and explain polar bonds and overall molecular dipoles in terms of bond dipoles and shape.’

Electronegativity influences how atoms share electrons, determining bond polarity and molecular dipoles. Understanding these ideas helps explain molecular behaviour, physical properties, and trends across chemical systems.

Electronegativity

Electronegativity is a central concept in chemical bonding because it describes how strongly an atom attracts the shared pair of electrons within a covalent bond. Differences in electronegativity between bonded atoms create unequal electron distribution, leading to bond polarity and influencing molecular shape, dipole formation, and intermolecular interactions.

Electronegativity: The tendency of an atom to attract the bonding electrons in a covalent bond.

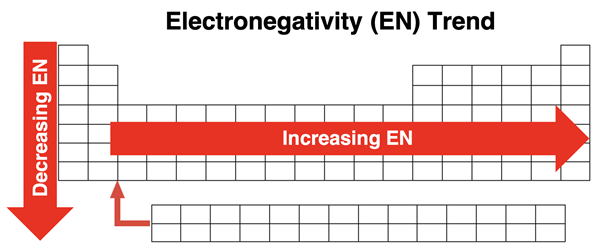

Electronegativity values follow key periodic trends essential for analysing bonding behaviour:

Increases across a period, as nuclear charge rises and atomic radius decreases.

Decreases down a group, as increased shielding and larger atomic radii weaken attraction for bonding electrons.

Elements with high electronegativity include nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine and chlorine, while metals generally exhibit low electronegativity.

Diagram showing the trend in electronegativity across periods and down groups, highlighting the increase towards the top-right of the periodic table. Source

These trends allow chemists to predict the type of bonding, relative bond strengths and the degree of polarity in molecules.

Polar Covalent Bonds

A polar covalent bond forms when two atoms share electrons unequally. This unequal sharing occurs because one atom has a higher electronegativity than the other. The more electronegative atom attracts the bonding pair more strongly, leading to partial charges.

Polar Bond: A covalent bond in which electron density is unevenly distributed due to a difference in electronegativity between two atoms.

A sentence explaining further: In polar bonds, the more electronegative atom gains a slight negative charge (δ–), whereas the less electronegative atom carries a slight positive charge (δ+).

The degree of polarity depends on the magnitude of the electronegativity difference:

Very small difference → non-polar covalent

Moderate difference → polar covalent

Very large difference → ionic character increases

However, even in bonds with moderate electronegativity differences, polarity does not automatically guarantee that the molecule itself will be polar. Molecular shape must also be considered.

Bond Dipoles

A bond dipole arises when a polar bond forms. It is a vector quantity with both magnitude and direction. The arrow points towards the more electronegative atom, with a cross at the tail next to the positive end.

Dipole (Bond Dipole): A separation of charge in a bond resulting from unequal electron sharing, represented as a vector from δ+ to δ–.

Between these definitions and molecular discussions lies an understanding of vector addition, which is crucial when several dipoles interact within the same molecule.

Molecular Dipoles

Even when individual bonds are polar, the molecule as a whole may or may not possess a molecular dipole. This depends on the arrangement of bond dipoles in three-dimensional space. Students must consider both bond polarity and molecular geometry using electron-pair repulsion ideas.

Key factors affecting molecular dipoles:

Symmetry

Direction of individual bond dipoles

Presence of lone pairs

Bond angles

If bond dipoles cancel due to symmetry, the molecule is non-polar. If they reinforce each other, the molecule is polar.

Symmetrical Molecules

Symmetrical shapes often lead to non-polar molecules even when the bonds are polar.

Examples include:

Linear molecules with identical terminal atoms

Trigonal planar structures with identical substituents

Tetrahedral molecules with four identical peripheral atoms

In these molecules, bond dipoles have equal magnitude and opposite orientation, cancelling out to give no net molecular dipole.

Asymmetrical Molecules

When molecular shapes lack symmetry or contain different elements around the central atom, the cancellation of dipoles does not occur. Lone pairs are especially significant because they introduce asymmetry.

Molecules with molecular dipoles tend to have:

Bent or V-shaped structures

Trigonal pyramidal shapes

Tetrahedral structures with mixed atoms

Uneven electron density due to lone pairs

Molecular dipoles influence several physical properties, including boiling points, solubility and intermolecular interactions such as permanent dipole–dipole forces.

How Electronegativity Determines Dipoles

Electronegativity differences generate the unequal electron distribution necessary for a dipole. However, the resulting molecular polarity depends on how these dipoles combine spatially.

Important points for OCR A-Level students:

Without electronegativity difference, no bond dipole forms.

Without asymmetry, no molecular dipole persists even if bonds are polar.

Lone pairs often create significant dipole moments due to their high electron density and effect on molecular geometry.

Key Applications of Dipoles in Chemistry

Understanding polar bonds and dipoles helps explain multiple chemical phenomena relevant to later A-Level topics:

Intermolecular Forces

Molecules with permanent dipoles experience dipole–dipole interactions, which are stronger than London dispersion forces.

Polar molecules dissolve more readily in polar solvents due to favourable dipole interactions.

Physical Properties

Bulk properties depend strongly on molecular polarity:

Higher boiling points in polar molecules due to stronger intermolecular forces

Higher solubility in water when molecules contain strong dipoles

Differences in viscosity, volatility and melting points across homologous series

Reactivity

Polar molecules often behave differently in chemical reactions because electrophiles and nucleophiles are attracted to partial charges. The polarity of a functional group can strongly affect reaction mechanisms and energetics.

Visualising Polarity

Students should develop the habit of:

Assessing electronegativity differences

Identifying δ+ and δ– ends of bonds

Drawing approximate bond dipoles

Analysing shape and symmetry

Predicting the resulting molecular dipole

Bullet-pointed method for evaluating polarity:

Identify each bond as polar or non-polar using electronegativity.

Determine molecular geometry from electron-pair repulsion.

Draw bond dipoles.

Consider vector addition of dipoles.

State whether dipoles cancel or reinforce.

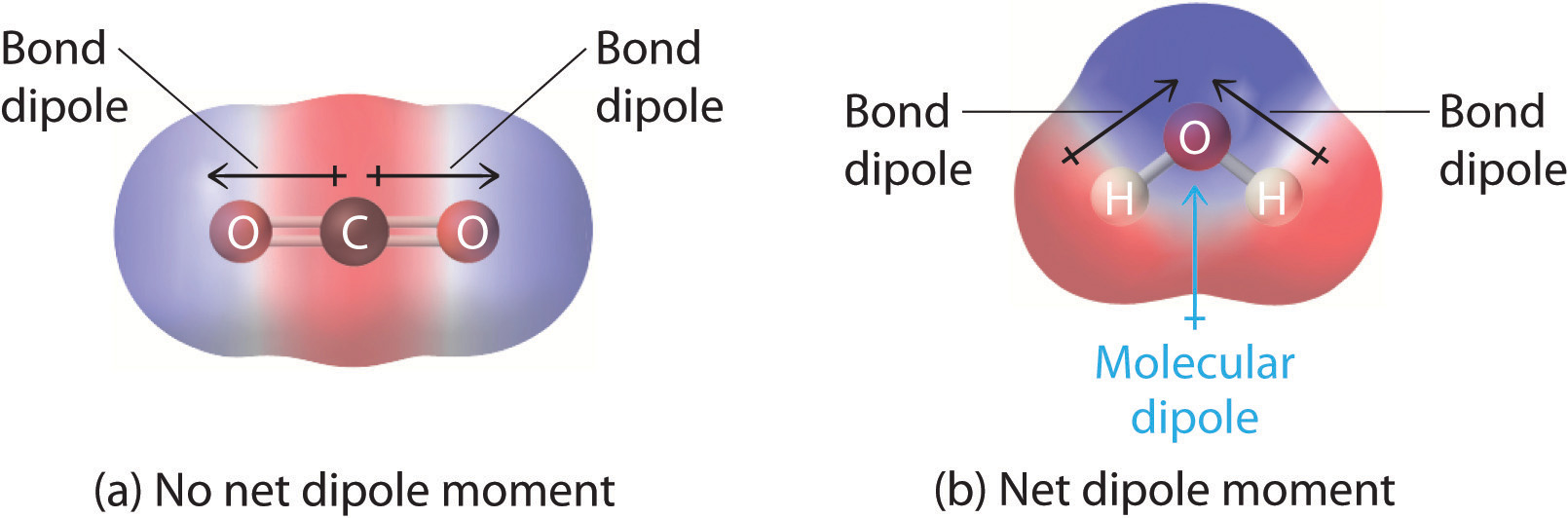

Diagram comparing CO₂ and H₂O, showing how individual bond dipoles combine to give overall molecular dipoles; extra contextual information on the page does not appear in the figure itself. Source

FAQ

Electronegativity differences create local dipoles within functional groups, and these dipoles influence reactivity and physical behaviour.

In a carbonyl group, oxygen’s high electronegativity creates a strong Cδ+–Oδ– dipole, making the carbon susceptible to attack by nucleophiles.

In a hydroxyl group, the O–H dipole enhances hydrogen bonding ability, increasing solubility and boiling point relative to non-polar groups.

Some molecules predicted to be symmetrical may distort slightly due to vibrational modes or subtle differences in bond lengths.

Small deviations can prevent complete cancellation of bond dipoles, leading to a weak but measurable dipole moment.

Polarisation of electron clouds by nearby atoms or interactions in the condensed phase may also contribute.

Lone pairs occupy more space than bonding pairs, increasing electron density on one side of a molecule.

This changes bond angles, usually compressing them, making bond dipoles less opposed.

Lone pairs also generate their own regions of high electron density, contributing directly to the direction and magnitude of the overall molecular dipole.

Magnitude depends not only on electronegativity, but also on:

Bond length

Degree of s-character in hybrid orbitals

Electron-withdrawing or electron-donating effects of nearby atoms

Shorter bonds and greater s-character concentrate electron density closer to nuclei, enhancing the dipole.

Polar molecules interact strongly with polar solvents via dipole–dipole interactions.

Where hydrogen bonding is possible, solubility increases further because solvent molecules can form directional interactions with polar regions of the solute.

Large hydrophobic regions reduce solubility, even if the molecule contains polar bonds, because non-polar sections disrupt solvent structure and limit favourable interactions.

Practice Questions

Explain why the H–F bond is more polar than the H–Cl bond.

(2 marks)

Fluorine has a higher electronegativity than chlorine. (1 mark)

Therefore, the electron pair in the H–F bond is attracted more strongly towards fluorine, increasing the bond dipole. (1 mark)

Carbon dioxide (CO2) contains polar C=O bonds, yet CO2 is a non-polar molecule.

Water (H2O) contains polar O–H bonds and is a polar molecule.

Using your understanding of electronegativity, bond dipoles and molecular shape, explain these observations.

(5 marks)

C=O and O–H bonds are polar due to electronegativity differences between atoms. (1 mark)

CO2 is linear, so the two C=O bond dipoles act in opposite directions. (1 mark)

The C=O dipoles cancel out because they have equal magnitude and are arranged symmetrically. (1 mark)

H2O is bent due to two lone pairs on oxygen, creating an asymmetrical shape. (1 mark)

The O–H bond dipoles in H2O do not cancel, resulting in an overall molecular dipole. (1 mark)