OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe hydrogen bonding (N–H, O–H, F–H); explain ice’s density and water’s high melting/boiling points; simple molecular lattices and properties.’

Hydrogen bonding profoundly influences physical properties of substances, especially water, producing unusual structural and thermal behaviours essential for understanding bonding, structure, and intermolecular forces.

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a strong type of intermolecular force that arises when hydrogen is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom. It plays a central role in explaining the structure and behaviour of many substances.

Requirements for Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding occurs only in molecules where hydrogen is bonded to nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine (N–H, O–H, F–H). These atoms possess high electronegativity and small atomic radius, enabling them to attract the bonding electrons strongly.

Hydrogen bond: A strong intermolecular attraction between a lone pair on an electronegative atom (N, O, F) and a hydrogen atom covalently bonded to another electronegative atom.

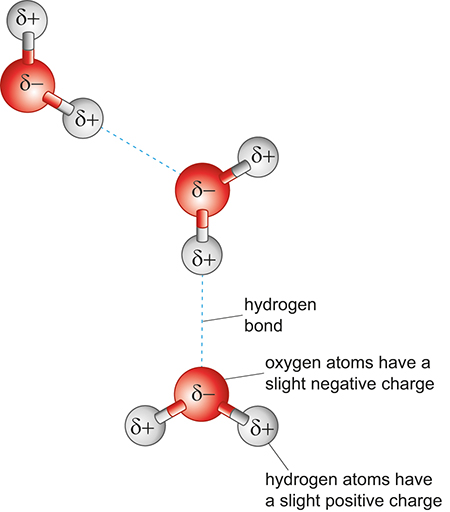

The significant difference in electronegativity between hydrogen and its bonding partner creates a highly polar bond. This polarity results in a partial positive charge on hydrogen (δ⁺) and a partial negative charge on the electronegative atom (δ⁻), allowing the formation of directional attractions.

How Hydrogen Bonds Form

Hydrogen bonds can be visualised as interactions between a lone pair and a δ⁺ hydrogen on a neighbouring molecule.

Diagram of hydrogen bonding between water molecules. Oxygen atoms (δ−) and hydrogen atoms (δ+) are shown with dashed lines indicating hydrogen bonds. This visual highlights how partial charges and molecular orientation allow hydrogen bonds to form between O–H groups in water; students can ignore the broader Martian context of the original page. Source

A normal sentence is required here before introducing another definition or highly formatted block, so this line ensures compliance with formatting rules.

Intermolecular forces: Attractions between molecules, weaker than covalent bonds, influencing physical properties such as melting and boiling points.

Water: Hydrogen Bonding and Anomalous Properties

Water exhibits unique anomalies due to its extensive hydrogen bonding. These anomalies are central to the OCR specification focus, particularly ice density and thermal properties.

Structure of Liquid Water

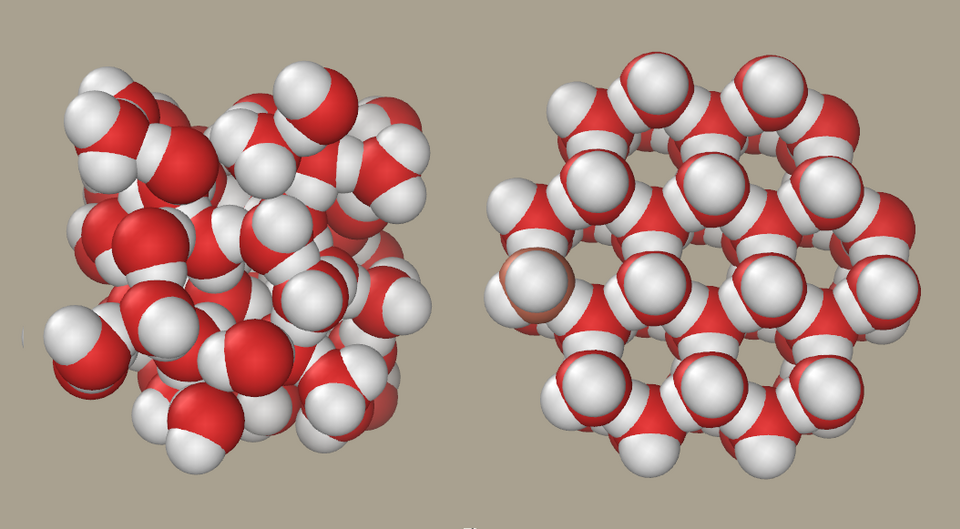

Liquid water contains a dynamic network of hydrogen bonds. As molecules move, hydrogen bonds continually break and reform. Key characteristics include:

A fluctuating open structure due to temporary hydrogen-bonded clusters

Higher density than ice, because molecular packing is less rigid

Significant energy required for changes of state

Structure of Ice and Its Lower Density

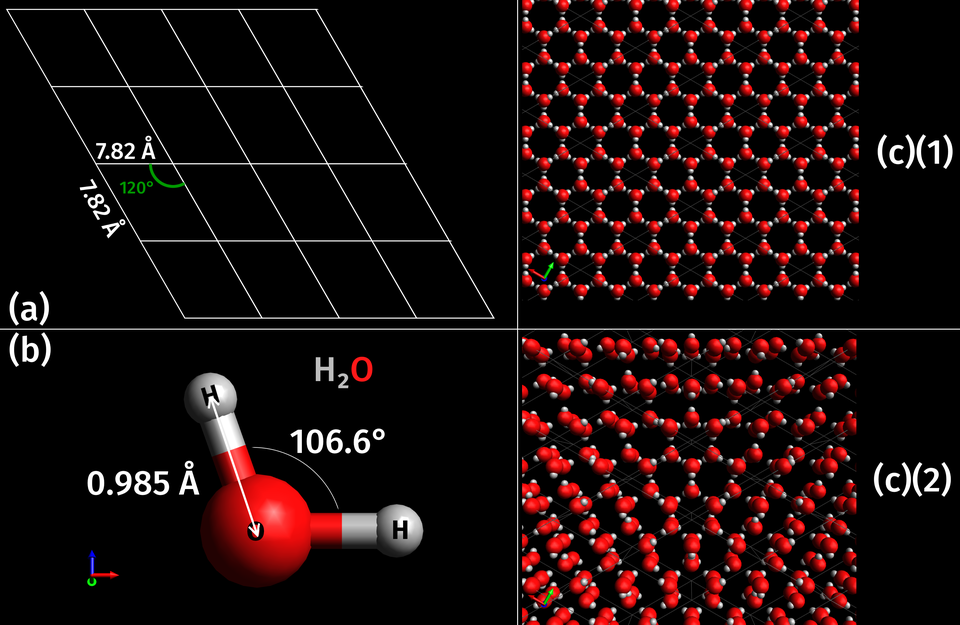

The hydrogen bonds in solid water form a tetrahedral lattice, in which each water molecule is surrounded by four others at a fixed distance. This ordered arrangement creates large open spaces within the lattice.

As a result:

Ice is less dense than liquid water, allowing it to float.

Space-filling models comparing the structure of liquid water and ice. The liquid shows molecules packed more closely together, whereas the ice lattice is more open due to fixed hydrogen bonds. This illustrates why ice is less dense than liquid water and therefore floats. Source

Molecules are held further apart than in the liquid state

Expansion upon freezing can exert pressure on containers and natural structures

These structural differences link directly to the hydrogen-bonding requirement in water molecules. The long-range, stable hydrogen-bonded arrangement explains why water expands when freezing.

High Melting and Boiling Points of Water

Water’s melting and boiling points are unusually high for a molecule of such small molar mass. This is because:

Many hydrogen bonds must be broken in order to melt ice or vaporise water

Substantial energy input is required compared with substances of similar size that lack hydrogen bonding

Thermal behaviour is dominated by intermolecular rather than molecular forces

Water’s ability to maintain the liquid state over a wide temperature range is largely attributable to the strength and prevalence of its hydrogen bonds.

Hydrogen Bonding in Other Molecules

Although the specification highlights N–H, O–H, and F–H, the principles extend to other hydrogen-bonded systems commonly encountered in A-Level Chemistry. For example:

Ammonia (NH₃) forms hydrogen bonds through lone pairs on nitrogen

Hydrogen fluoride (HF) shows particularly strong hydrogen bonding due to fluorine’s very high electronegativity

Alcohols and carboxylic acids exhibit hydrogen bonding via O–H groups, significantly affecting solubility and boiling points

However, the extent of hydrogen bonding varies, depending on molecular geometry and the number of available lone pairs.

Simple Molecular Lattices

Some substances form simple molecular lattices in the solid state, in which discrete molecules are arranged in a regular pattern held together by intermolecular forces. Hydrogen bonding can play a major role in stabilising these structures.

Characteristics of Simple Molecular Lattices

A simple molecular lattice is composed of individual molecules, not ions or atoms, and its properties depend on the intermolecular forces present. Key features include:

Low melting and boiling points due to relatively weak intermolecular forces

Solids that are often soft and brittle

Poor electrical conductivity, because no mobile charged particles are present

Structures governed by the strength and orientation of intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding or London dispersion forces

In water ice, the simple molecular lattice is dominated by hydrogen bonding, creating an expansive three-dimensional arrangement that stabilises the solid form at low temperatures.

Three-dimensional crystal lattice of hexagonal ice (Ice Ih), showing water molecules connected in a hydrogen-bonded framework. The open, tetrahedral arrangement explains the relatively low density of ice and its classification as a simple molecular lattice. Crystallographic elements such as unit cells exceed OCR requirements and can be treated as optional extension material. Source

Influence of Hydrogen Bonding on Lattice Properties

Hydrogen bonding critically shapes lattice behaviour:

Rigid, open frameworks, especially in substances like ice

Enhanced stability in solid-state forms of alcohols and acids

Distinctive crystal shapes resulting from directional hydrogen bonds

Thermal properties that differ markedly from those of molecules of similar molar mass

Hydrogen bonding therefore represents a major theme within bonding and structure, linking directly to water’s anomalies and the behaviour of simple molecular lattices in OCR A-Level Chemistry.

FAQ

The strength of a hydrogen bond depends on the electronegativity of the atom bonded to hydrogen and the distance between the interacting molecules.

More electronegative atoms (F > O > N) produce more polar bonds, creating stronger attractions.

Shorter hydrogen bond distances also increase bond strength, as molecules are held more tightly within the structure.

Hydrogen bonds pull water molecules strongly towards one another at the liquid–air boundary.

This creates a cohesive “film” where molecules at the surface experience a net inward force.

The result is high surface tension compared with similarly sized molecules lacking hydrogen bonding.

Molecules capable of forming hydrogen bonds with water often dissolve readily.

For example, alcohols and amines interact with water via O–H or N–H groups, forming new hydrogen bonds that stabilise them in solution.

Non-polar molecules lack this capability, so water cannot solvate them effectively.

Hydrogen bonds align along a specific axis between the lone pair of one molecule and the hydrogen of another.

The directional nature forces molecules into organised, repeating patterns such as the tetrahedral arrangement in ice.

This gives rise to open lattice structures with lower density.

Viscosity increases when intermolecular forces hinder molecular movement.

Hydrogen bonding creates temporary networks that resist flow, raising viscosity.

Liquids with more extensive hydrogen bonding, such as glycerol, show much higher viscosity than those with fewer hydrogen-bonding sites.

Practice Questions

Explain why ice is less dense than liquid water.

(2 marks)

1 mark: States that ice has an open or expanded structure / molecules are further apart.

1 mark: Refers to hydrogen bonding creating a tetrahedral lattice with gaps / open spaces.

Hydrogen bonding leads to several unusual physical properties of water.

Describe how hydrogen bonding forms in water and explain two physical properties of water that arise from this type of bonding.

(5 marks)

1 mark: Hydrogen bonding described as an attraction between a lone pair on oxygen and a delta positive hydrogen on another molecule.

1 mark: Identifies that the O–H bond is highly polar, enabling hydrogen bonding.

1–2 marks: Explains a property linked to hydrogen bonding, such as high boiling/melting point due to many hydrogen bonds requiring significant energy to break.

1–2 marks: Explains a second property, such as ice being less dense because hydrogen bonding forms a tetrahedral lattice with molecules held further apart than in liquid water.