OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain permanent dipole–dipole interactions and induced dipole–dipole (London dispersion) forces, collectively termed van der Waals’ forces.’

Introduction

Intermolecular forces determine many physical properties of substances, including volatility, solubility and boiling points. Understanding these weak but influential forces is essential for explaining molecular behaviour.

Intermolecular Forces: Permanent and Induced Dipoles

Intermolecular forces are weak attractions occurring between molecules, in contrast to covalent and ionic bonds which operate within molecules or lattices. These forces are collectively known as van der Waals’ forces, an umbrella term covering multiple types of dipole-based interactions. Although individually weak, they significantly influence physical behaviour, especially in molecular substances with low overall polarity.

Understanding Dipoles and Electron Distribution

A dipole arises when there is an uneven distribution of electron density in a bond or molecule, generating regions of slight positive and negative charge. Molecules interact when these charge differences influence neighbouring species. The primary intermolecular forces covered in this section are permanent dipole–dipole interactions and induced dipole–dipole (London dispersion) forces.

Permanent Dipole–Dipole Interactions

Permanent dipole–dipole interactions occur when molecules possess an inherent, persistent dipole due to differences in electronegativity between bonded atoms and an asymmetric molecular shape.

Permanent Dipole–Dipole Interaction: An attraction between molecules that each possess a permanent dipole, arising from uneven electron distribution and fixed partial charges.

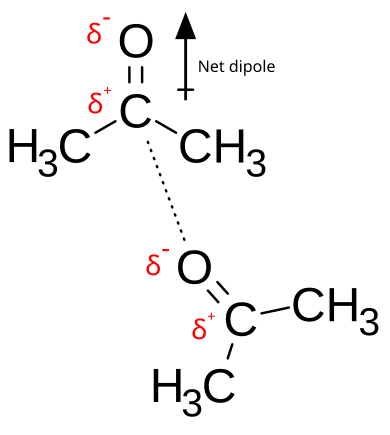

These interactions originate from the orientation of δ+ and δ– ends of neighbouring molecules, encouraging alignment that minimises potential energy.

Permanent dipoles occur in molecules such as HCl, CH₂O and SO₂, where the electronegativity differences and asymmetry prevent charge cancellation.

Permanent dipole–dipole interactions between two acetone molecules. The δ− region on the oxygen atom is attracted to the δ+ region on the neighbouring molecule, illustrating alignment of permanent dipoles. Source

The strength of these interactions depends on:

Magnitude of the molecular dipole

Orientation of molecules

Proximity of interacting species

Even though these forces are stronger than London dispersion forces, they remain substantially weaker than covalent or ionic bonds.

How Permanent Dipole–Dipole Interactions Influence Properties

Molecules with permanent dipoles typically exhibit:

Higher boiling points than non-polar molecules of similar mass

Greater solubility in polar solvents

Directional intermolecular attraction, as dipoles attempt to align δ+ to δ–

These properties relate directly to the unavoidable and consistent uneven electron distribution in each molecule.

Induced Dipole–Dipole (London Dispersion) Forces

Induced dipole–dipole forces occur in all molecular substances, whether polar or non-polar. They originate from instantaneous fluctuations in electron density.

Induced Dipole–Dipole (London Dispersion) Forces: Weak attractions resulting from temporary dipoles formed when electron distribution fluctuates, inducing dipoles in neighbouring molecules.

These forces become significant in large molecules with many electrons, as greater electron cloud distortion produces stronger temporary dipoles.

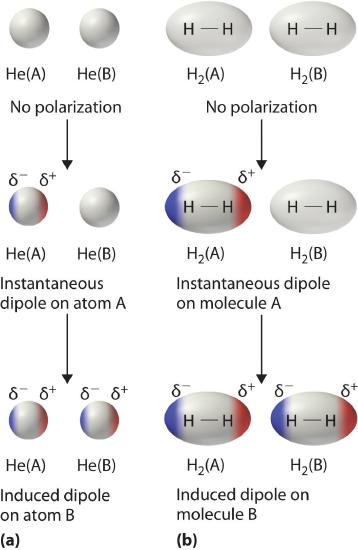

Formation of instantaneous and induced dipoles leading to London dispersion forces. An instantaneous dipole in one atom or molecule induces a dipole in its neighbour, creating a brief attraction. The specific examples (He and H₂) include additional detail but clearly model induced dipole interactions. Source

After these temporary dipoles form, neighbouring molecules respond:

A momentary δ– region induces a δ+ region nearby

Molecules briefly attract one another

Dipoles constantly form, shift and collapse

Factors Affecting the Strength of London Dispersion Forces

The strength of London dispersion forces increases when:

Number of electrons increases (larger atomic or molecular mass)

Surface area increases (long, unbranched molecules form stronger interactions)

Molecules are easily polarised (electron clouds deform readily)

These factors explain trends such as:

Noble gases increasing in boiling point from He → Xe

Higher boiling points in long-chain alkanes compared with branched isomers

Comparison of Permanent and Induced Dipole Forces

Although both forces depend on variations in electron distribution, key differences include:

Permanent dipoles exist continuously; induced dipoles are temporary

Permanent dipole interactions are generally stronger

Induced dipole forces operate in all molecules

Permanent dipole forces rely on electronegativity and molecular shape; induced dipoles rely on electron movement and cloud size

Bullet-point contrasts help clarify these distinctions:

Origin:

Permanent: fixed electronegativity differences

Induced: fleeting electron cloud shifts

Prevalence:

Permanent: only in polar molecules

Induced: universal across all molecules

Relative strength:

Permanent > induced (though large molecules may have strong London forces)

Collective Term: van der Waals’ Forces

Both permanent dipole–dipole interactions and induced dipole–dipole forces fall under the collective name van der Waals’ forces.

van der Waals’ Forces: A group of weak intermolecular forces including permanent dipole–dipole interactions and induced dipole–dipole (London dispersion) forces.

These forces underpin many molecular-level properties central to physical chemistry.

Role of Intermolecular Forces in Physical Properties

Intermolecular forces strongly influence bulk properties:

Boiling and melting points depend on energy required to overcome these forces

Volatility decreases as intermolecular forces strengthen

Solubility patterns reflect compatibility of molecular polarity

Viscosity and surface tension increase with stronger intermolecular attractions

These relationships illustrate the importance of intermolecular forces across organic, inorganic and physical chemistry.

Recognising Intermolecular Forces from Molecular Structure

Students must be able to identify whether a molecule forms permanent or induced dipole interactions by considering:

Bond polarity (electronegativity differences)

Molecular shape (symmetry determines whether dipoles cancel)

Molecular mass and size

Electron cloud characteristics

Bullet-point guidance:

Molecule non-polar → only London forces present

Molecule polar and asymmetric → permanent dipole–dipole + London forces

Giant ionic or metallic structures → not applicable; intermolecular forces describe simple molecules only

This systematic approach ensures accurate predictions in later topics involving solubility, boiling point trends and molecular behaviour.

FAQ

A molecule must have polar bonds and lack full symmetry for a permanent dipole to exist. Even if individual bonds are polar, overall symmetry can cause dipole cancellation.

For example, carbon dioxide has polar C–O bonds but a linear, symmetrical arrangement, resulting in no permanent dipole.

In contrast, molecules such as chloromethane or sulfur dioxide are asymmetric, so their dipoles combine rather than cancel, allowing permanent dipole–dipole interactions to form.

London dispersion forces increase with the number of electrons and the size of the electron cloud. Large, non-polar molecules therefore experience stronger induced dipole–dipole forces.

In some cases, these temporary forces can exceed the strength of permanent dipole interactions in small polar molecules.

Key contributors include:

molecular mass

molecular surface area

ease of electron cloud distortion (polarisability)

Polarisability increases with electron number and with the distance of outer electrons from the nucleus. Large atoms with diffuse electron clouds distort more easily.

Structural features also influence polarisability: elongated molecules create more contact area for electron clouds to interact.

Heavy halogens such as iodine form stronger induced dipoles than lighter ones like fluorine.

Miscibility depends on how well the intermolecular forces in one liquid interact with those in another.

Liquids mix effectively when their dominant forces match in type and strength:

polar with polar (dipole–dipole compatible)

non-polar with non-polar (London forces comparable)

A mismatch, such as strong dipoles meeting only London forces, usually leads to immiscibility.

Long, unbranched chains provide larger contact surfaces for temporary dipoles to interact, strengthening induced dipole–dipole forces.

Branched molecules are more compact, reducing how closely molecules can pack and weakening intermolecular contact.

This explains why branched isomers typically have lower boiling points than their straight-chain counterparts.

Practice Questions

Explain the difference between a permanent dipole–dipole interaction and an induced dipole–dipole (London dispersion) force.

(2 marks)

Award up to 2 marks for the following points:

1 mark: Permanent dipole–dipole interactions occur between molecules with a permanent dipole due to uneven electron distribution.

1 mark: Induced dipole–dipole forces arise from temporary dipoles formed when electron clouds fluctuate and induce dipoles in neighbouring molecules.

A student is comparing the intermolecular forces present in three substances: chloroethane (C2H5Cl), hexane (C6H14), and hydrogen chloride (HCl).

Using your understanding of permanent dipoles and induced dipoles, explain:

(a) which intermolecular forces each substance experiences

(b) why the boiling points of hexane and chloroethane differ, despite having similar molar masses.

(5 marks)

Award up to 5 marks for the following points:

(a) Intermolecular forces present (up to 3 marks):

1 mark: Chloroethane has both permanent dipole–dipole interactions and London dispersion forces (due to polarity of C–Cl bond).

1 mark: Hexane has only London dispersion forces (non-polar molecule).

1 mark: Hydrogen chloride has permanent dipole–dipole interactions and London dispersion forces (polar molecule).

(b) Explanation of boiling point differences (up to 2 marks):

1 mark: Hexane, although non-polar, has stronger London dispersion forces due to its larger number of electrons and larger surface area.

1 mark: Chloroethane has permanent dipole–dipole interactions, but its smaller electron cloud means its London forces are weaker than those in hexane, affecting overall boiling point comparison.