OCR Specification focus:

‘Successive ionisation energy data reveal shell structure and allow prediction of an element’s group by observing large jumps between shells.’

Introduction

Successive ionisation energies reveal how strongly electrons are held in different shells. Large increases between specific ionisation steps provide clear evidence of shell structure and enable group prediction.

Understanding Successive Ionisation Energies

Successive ionisation energies refer to the energy required to remove electrons one-by-one from the same gaseous atom. Each successive energy value becomes larger because once an electron is removed, the remaining electrons experience a greater effective nuclear charge.

Ionisation Energy: The energy required to remove one mole of electrons from one mole of gaseous species.

A key feature of successive ionisation energy data is the presence of large jumps, which occur when the removal process reaches an inner electron shell that is much closer to the nucleus and far more strongly attracted.

Successive ionisation energy data reveal shell structure and allow prediction of an element’s group by observing large jumps between shells.

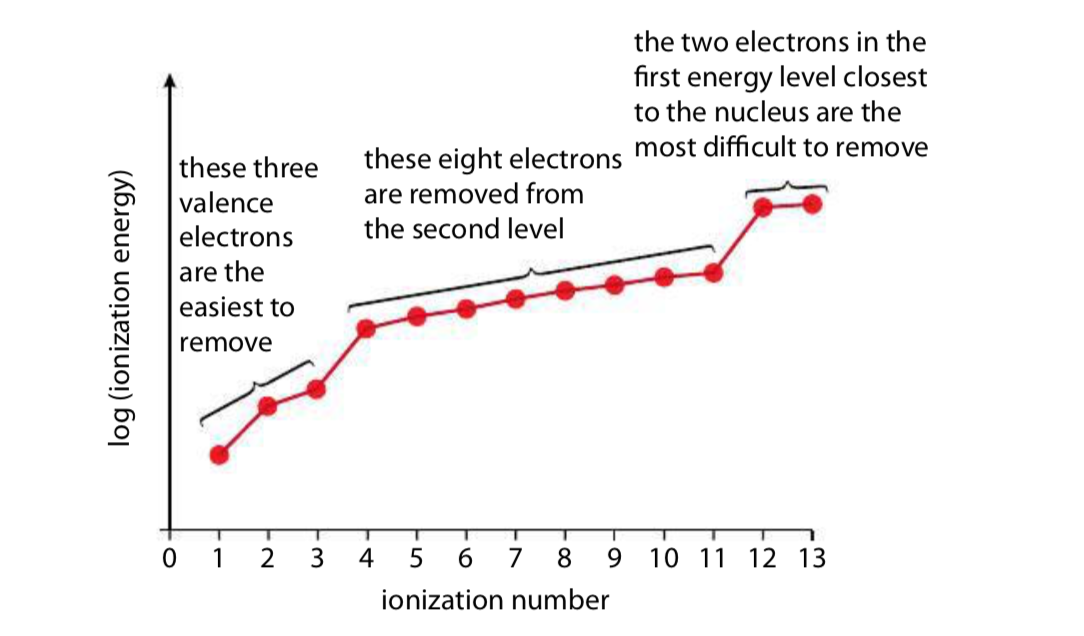

This graph shows the successive ionisation energies of aluminium plotted against ionisation number on a logarithmic scale. The three regions correspond to aluminium’s electron shells, with a clear large jump between valence and core electrons. The log scale is an additional detail beyond the OCR specification but only serves to make the changes easier to visualise. Source

Why Successive Values Increase

As electrons are removed, the same number of protons attracts fewer electrons.

The attraction per electron increases due to reduced electron–electron repulsion.

Removing an electron from a new shell requires significantly more energy because inner shells have:

Lower shielding

Smaller atomic radius

Stronger electrostatic attraction to the nucleus

Identifying Shell Structure from Data

Successive ionisation energy data typically form a sequence of steadily increasing values, interrupted by one or more marked discontinuities. These discontinuities correspond to changes in shell.

Large increases indicate that an electron is being removed from a shell closer to the nucleus. This is because the inner shell electrons are more tightly bound due to significantly reduced shielding and a higher effective nuclear charge.

The Principle of Large Jumps

A “large jump” is a sudden rise in required energy that is much greater than the increase between earlier consecutive ionisation steps.

Such a jump reveals:

The number of electrons in the outer shell

The point at which the next electron lies in a lower energy level

The shell structure of the atom, which is fundamental to determining the position of the element in the periodic table

Deducing the Group of an Element

Successive ionisation energy patterns allow students to deduce the group number by identifying how many electrons are removed before the first large jump occurs.

Method for Predicting an Element’s Group

Observe the ordered list of ionisation energies.

Count how many electrons can be removed before encountering the first major jump.

The number removed corresponds to the number of outer-shell electrons.

The element's group number in the periodic table equals this number (for Groups 1–2 and 13–18).

This approach works because elements within the same group have the same number of electrons in their outer shell, which leads to similar successive ionisation energy patterns.

The number of electrons removed before the large jump equals the number of outer-shell electrons for a main-group element and therefore reveals its group in the periodic table.

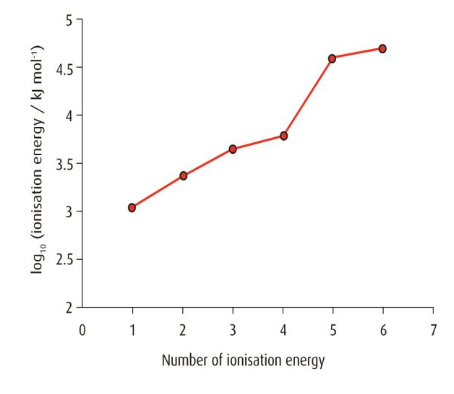

This graph plots log₁₀ of successive ionisation energies for an element, with a sharp jump between the fourth and fifth values indicating the transition from valence electrons to a core shell. This provides a clear visual method for identifying the element’s group. The use of a logarithmic scale is an additional detail beyond the syllabus but simply compresses the wide energy range for clarity. Source

Why Large Jumps Occur at Specific Points

Large jumps occur because:

After all outer-shell electrons are removed, the next electron must come from an inner shell.

Inner-shell electrons are closer to the nucleus and experience much stronger nuclear attraction.

Removing one of these electrons requires a disproportionately high amount of energy.

Between outer-shell electrons, increases in ionisation energy remain comparatively modest because these electrons experience similar shielding and attraction.

Electron Configuration Link

Successive ionisation energy patterns strongly reflect the arrangement of electrons within shells. When successive energies are grouped into similar clusters with spaced-out, high-energy gaps between them, this mirrors how electrons fill principal energy levels.

The pattern confirms:

Number of electrons in each shell

Principle that energy increases closer to the nucleus

The direct relationship between structure and periodic properties

Factors Affecting Successive Ionisation Energies

Several key factors influence the magnitude and pattern of successive ionisation energies:

Nuclear Charge

A higher nuclear charge increases the attraction between nucleus and electrons, raising ionisation energies across all steps.

Atomic Radius

A larger atomic radius reduces nuclear attraction to the outer-shell electrons, lowering early ionisation energies but still causing large jumps upon reaching inner shells.

Electron Shielding

Shielding by inner-shell electrons reduces effective nuclear charge experienced by outer-shell electrons. As shielding decreases, energy demands for electron removal rise sharply.

Sub-shell Effects

Although successive ionisation energy trends mainly reflect shell structure, variations also occur between sub-shells:

Electrons in s-sub-shells are slightly closer to the nucleus than those in p-sub-shells

Removing paired electrons may require more energy than removing unpaired electrons due to repulsion effects

These factors fine-tune successive energy values without altering the position of major jumps.

Using Successive Ionisation Energy Graphs

Graphs provide an efficient visual tool to identify large jumps and interpret shell structure. Students should pay attention to:

Relative heights of consecutive bars or points

Locations of sharp discontinuities

The number of data points before a marked increase

Clusters of values corresponding to electrons within the same shell

Step-by-Step Interpretation

Start at the first ionisation energy and examine each successive value.

Identify clusters of moderate increases.

Highlight any point where the energy value rises dramatically.

Determine the number of electrons removed before the jump.

Match this number to the group number of the element.

This stepwise approach aligns with the OCR emphasis on using data to deduce group membership and understand periodic behaviour grounded in electron structure.

FAQ

A large jump is not defined by a specific numerical threshold but by its relative size compared with the previous increases.

Normal increases are usually steady and progressive because electrons are removed from the same shell.

A large jump occurs when the next electron must be removed from an inner shell, which results in an increase several times larger than the earlier steps.

Students should compare differences rather than absolute values.

Multiple large jumps indicate several transitions to increasingly deeper electron shells.

Each jump reflects moving from a valence shell to a core shell, then from one core shell to an even more tightly held inner shell.

This pattern becomes clearer for elements with many electron shells, especially those beyond Period 3.

Effective nuclear charge helps explain why inner-shell electrons are so much harder to remove.

Outer electrons experience more shielding and therefore weaker attraction.

As you move to inner shells, shielding decreases sharply, making the nucleus’ attraction much stronger.

This difference in attraction is the fundamental reason for the large energy discontinuities.

Not usually for the first few ionisations. Elements in the same group have the same number of valence electrons, so their early ionisation patterns appear similar.

However, later values may differ due to:

Differences in nuclear charge

Slight variations in shielding

Shell contraction effects in heavier elements

These differences are subtle and not typically used for group identification at A level.

Successive ionisation energies can span several orders of magnitude—from hundreds to tens of thousands of kJ mol–1.

A standard linear scale would compress the lower values and exaggerate the higher ones.

A logarithmic scale:

Spreads out the data more evenly

Makes large jumps easier to compare visually

Helps highlight shell transitions without distorting relationships between values

Practice Questions

The successive ionisation energies of an element show a very large increase between the third and fourth ionisation energies.

Explain what this large increase indicates about the electron structure of the element.

(2 marks)

Large increase indicates that the fourth electron must be removed from an inner shell (1)

Therefore, the element has three electrons in its outer shell / is in Group 13 (1)

A student analyses the successive ionisation energies of an unknown element X. The first six ionisation energies (in kJ mol–1) are shown below:

IE1 = 577

IE2 = 1820

IE3 = 2740

IE4 = 11 600

IE5 = 14 800

IE6 = 18 400

(a) Identify the group of element X in the periodic table. (1)

(b) Explain fully how the data support your answer. Refer to electron shells and attraction. (4)

(5 marks)

(a) Group 3 / Group 13 (1)

(b)

First three ionisation energies increase gradually, so three outer-shell electrons (1)

Very large jump between IE3 and IE4 shows removal of an inner-shell electron after the third (1)

Inner-shell electrons are much closer to the nucleus / experience stronger nuclear attraction (1)

Therefore, the element must have three valence electrons and belongs to Group 3 / Group 13 (1)