OCR Specification focus:

‘Metallic bonding is strong electrostatic attraction between positive ions and delocalised electrons, forming giant metallic lattice structures with characteristic properties.’

Metallic bonding underpins the structure and physical behaviour of metallic elements across the Periodic Table. This topic explores how metallic bonding arises, the nature of the giant metallic lattice, and the origins of common metal properties.

Metallic Bonding: Fundamental Principles

Metallic bonding forms when metal atoms release some of their outer-shell electrons, producing positive metal ions surrounded by a sea of delocalised electrons. This creates a lattice of charged particles, generating a strong, non-directional electrostatic attraction.

Metallic Bonding: The strong electrostatic attraction between positive metal ions and delocalised electrons in a giant metallic lattice.

Metallic bonding strength varies depending on charge density and electron availability. Metals with a higher ionic charge and more delocalised electrons typically exhibit stronger bonding and higher melting points.

The Formation of Giant Metallic Lattices

The arrangement of particles in metals forms a giant metallic lattice, an extended three-dimensional structure repeating throughout the solid.

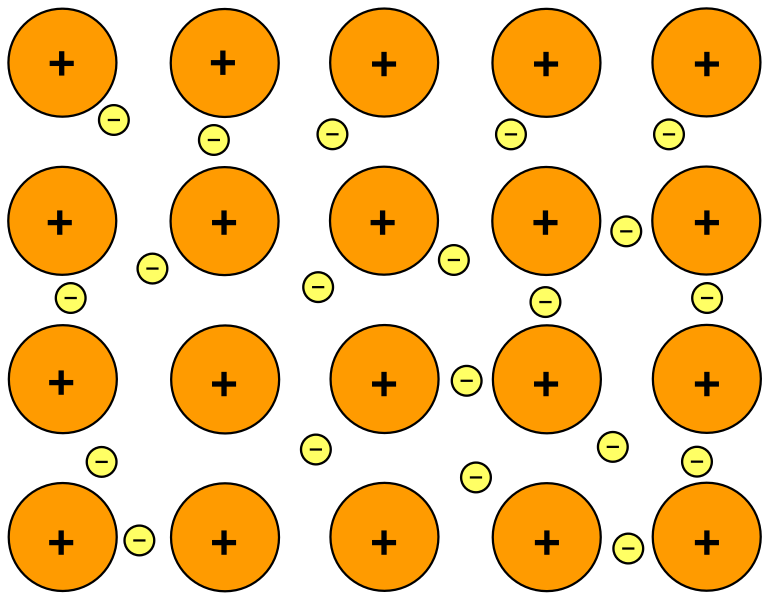

A schematic representation of metallic bonding, showing positive metal ions arranged in a lattice and surrounded by a sea of delocalised electrons. The diagram highlights how non-directional electrostatic attraction operates throughout the giant metallic structure. This image is simplified but accurately represents the level of detail needed for OCR A-Level Chemistry. Source

Key structural characteristics include:

Regular, closely packed arrangement of metal ions

Delocalised electron sea providing cohesion and conductivity

Non-directional bonding, meaning metallic structures can maintain integrity under stress

These structural features give rise directly to the characteristic physical properties observed in all metals.

Delocalised Electrons and Metallic Properties

The delocalisation of electrons explains many metal behaviours. Because these electrons are mobile, they enable several essential properties.

Electrical Conductivity

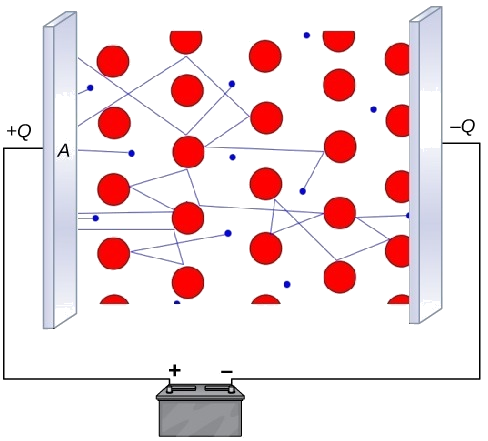

Metals conduct electricity because delocalised electrons act as charge carriers.

Diagram of the electron-sea model under an applied potential difference, with delocalised electrons moving through a lattice of positive metal ions between oppositely charged plates. It illustrates how mobile electrons carry charge through the metal, explaining electrical conductivity in both solid and liquid states. The presence of a battery and charged plates adds context but remains fully consistent with the OCR A-Level treatment. Source

Thermal Conductivity

Metals conduct heat efficiently due to:

Vibrations of ions transferring kinetic energy

Mobility of delocalised electrons distributing energy rapidly throughout the lattice

This dual mechanism makes metals among the best thermal conductors.

Strength, Malleability, and Ductility

The metallic lattice resists deformation due to strong electrostatic attraction. However, metals can still be shaped because the bonding is non-directional: ions can slide over one another without breaking bonds.

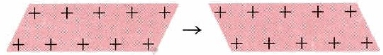

Malleability

Malleability refers to a metal’s ability to be hammered or rolled into sheets. Because the layers of ions can move while remaining attracted to the electron sea, the structure does not fracture.

Simplified diagram showing two snapshots of a metallic lattice, before and after layers of positive ions have slid past each other. The positions of the ions change, but the bonding environment remains similar, so the metal changes shape instead of shattering. The image focuses solely on malleability and does not introduce concepts beyond those required in the OCR specification. Source

Ductility

Ductile metals can be drawn into wires. The same principle of sliding layers preserves cohesion during stretching.

These mechanical properties contrast with giant covalent or ionic structures, where directional or rigid bonding prevents movement without fracture.

Melting and Boiling Points of Metals

Melting and boiling points provide insight into metallic bonding strength. Metals tend to have high melting points because breaking the lattice requires overcoming strong electrostatic forces.

Factors influencing melting and boiling points include:

Ionic charge: higher charge produces stronger attraction

Metallic radius: smaller ions hold electrons more tightly

Number of delocalised electrons: more electrons increase bonding strength

Across a period, melting points generally increase from Group 1 to transition metals as bonding becomes stronger.

Comparing Metallic Structures Across Elements

Although the principle of metallic bonding is universal, structures vary subtly:

Group 1 Metals

Contain one delocalised electron per atom

Produce relatively weak metallic bonds

Have low melting and boiling points

Are soft and easily cut

Group 2 Metals

Contribute two electrons per atom

Form stronger metallic bonds

Have higher melting points than Group 1 metals

Transition Metals

Possess partially filled d-subshells

Can release more delocalised electrons

Exhibit especially strong metallic bonding

Have high density, high tensile strength, and very high melting points

These differences illustrate how electron configuration shapes metallic behaviour.

Giant Metallic Lattices: Structural Features in Detail

A giant metallic lattice consists of millions of ions arranged in repeating layers. Important structural points include:

Each ion occupies a fixed position in the lattice

Electrons are free to move between ions

Lattice arrangement maximises packing efficiency

The structure is rigid yet flexible due to electron mobility

Delocalised Electrons: Electrons not associated with a single atom or bond, free to move throughout the lattice.

Movement of delocalised electrons ensures metals respond efficiently to thermal and electrical stimuli while maintaining structural integrity.

Linking Metallic Bonding to Observed Properties

The connection between bonding and physical behaviour can be summarised as the following relationships:

Strong bonding → high melting points, strength, and hardness

Electron mobility → electrical/thermal conductivity

Non-directional bonding → malleability and ductility

Because metallic bonding does not depend on fixed directional orientations, metals remain cohesive under stress, unlike ionic or covalent networks.

Additional Metallic Properties

Other useful features include:

Density: closely packed ions produce high densities

Lustre: electrons reflect light at the surface

Sonority: metals vibrate uniformly when struck due to lattice regularity

These arise naturally from the rigid structure and electron interactions.

Bonding Variation and Alloy Formation

Metals can be mixed to form alloys, which modify lattice structure by introducing differently sized ions. This disrupts regular packing and alters mechanical properties.

Important alloy effects:

Increased strength: disrupted layers reduce sliding

Altered conductivity: fewer delocalised pathways

Enhanced corrosion resistance in some combinations

Alloys demonstrate how adjusting lattice composition fine-tunes metallic properties in practical applications.

FAQ

Metallic radius affects how closely positive ions pack within the lattice. Smaller ions sit nearer to the delocalised electrons, strengthening the electrostatic attraction.

Larger metallic radii increase ion–electron distance, weakening the bonding. This is why metals lower down a group generally have weaker metallic bonding.

The number of delocalised electrons depends on how many outer-shell electrons a metal can release into the lattice.

Group 1 metals release one electron

Group 2 metals release two electrons

Transition metals may release additional d-electrons

A greater number of delocalised electrons increases the overall strength of metallic bonding.

Hardness depends on how strongly ions are held in place and how readily layers can slide.

High charge density creates a tighter, more rigid lattice

Lower charge density and fewer delocalised electrons make metals softer

The presence of impurities or alloying elements obstructs layer movement, increasing hardness

Alkali metals have one delocalised electron per atom, low charge density, and relatively large radii, producing weak metallic bonding.

Transition metals typically have:

smaller radii

higher ionic charge

more delocalised electrons

These features give them stronger metallic bonding, higher density, and greater mechanical strength.

Magnetism comes from unpaired electrons in atomic orbitals rather than from metallic bonding.

Transition metals often have unpaired d-electrons whose spins can align across the lattice.

Iron, cobalt, and nickel display ferromagnetism because their electron configurations allow spin alignment on a large scale.

Practice Questions

Explain why metals are able to conduct electricity in the solid state.

(2 marks)

Metals contain delocalised electrons. (1)

These electrons are free to move through the lattice and carry charge. (1)

Magnesium has a higher melting point than sodium.

Using ideas about metallic bonding and structure, explain why the melting point of magnesium is higher.

In your answer, refer to:

the charge on the ions

the number of delocalised electrons

the strength of the metallic lattice.

(5 marks)

Magnesium forms ions with a higher charge than sodium (Mg2+ compared to Na+). (1)

Magnesium releases more delocalised electrons into the lattice. (1)

Higher charge density leads to stronger electrostatic attraction between ions and electrons. (1)

Metallic bonding in magnesium is therefore stronger. (1)

More energy is required to break the metallic lattice, giving a higher melting point. (1)