OCR Specification focus:

‘Chlorination kills bacteria but poses hazards and by-product risks. Halide ions identified by precipitation with Ag+, followed by ammonia to distinguish halides.’

Water treatment relies on controlled chemical processes to make water safe for consumption and hygiene. This subtopic explores how chlorine is used, why it is effective, the associated risks, and how halide ions are tested during qualitative analysis. Students must understand both the chemical principles and the practical considerations that inform real-world water purification and analytical procedures.

Water Treatment and the Role of Chlorination

Chlorine is added to water supplies because it acts as a powerful oxidising agent, capable of destroying harmful microorganisms. When chlorine dissolves in water, it undergoes disproportionation, forming a mixture of species that contribute to disinfection.

Chlorine Chemistry in Water

Chlorine reacts with water to produce chloric(I) acid and hydrochloric acid, each playing a role in microbial control.

Chlorine–Water Reaction (Cl₂ + H₂O ⇌ HClO + HCl)

Cl₂ = Chlorine gas (molecule)

H₂O = Water

HClO = Chloric(I) acid, active oxidising species

HCl = Hydrochloric acid

Hypochlorous acid is the main oxidising species responsible for killing bacteria in treated water.

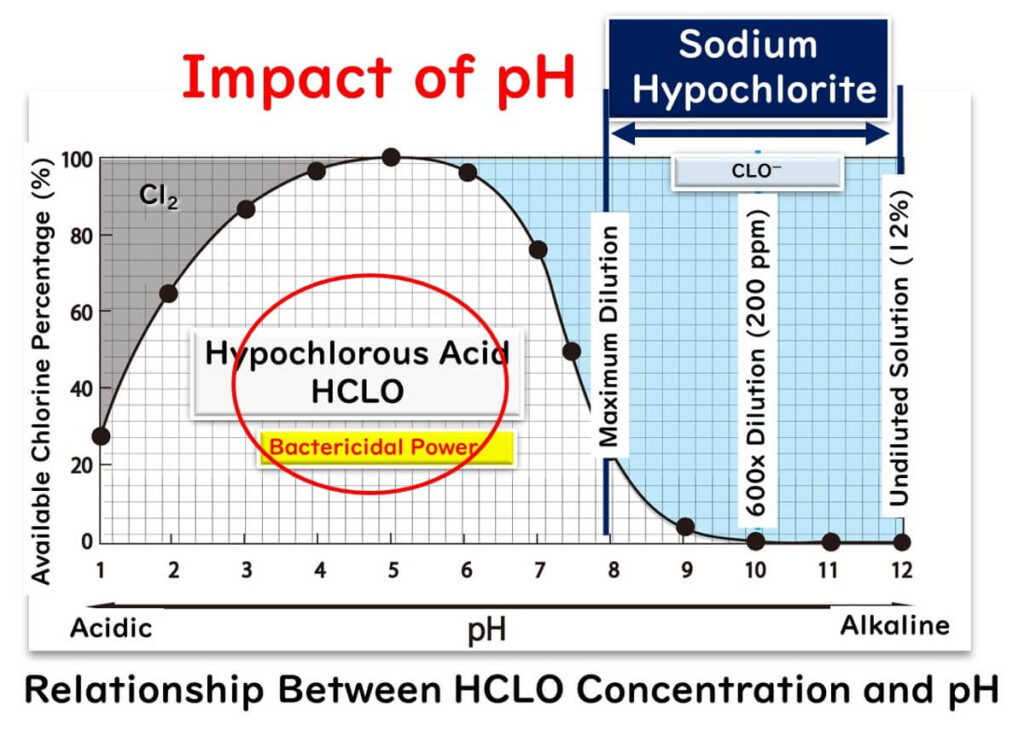

Graph showing how the fraction of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and its bactericidal effectiveness vary with pH compared with hypochlorite from sodium hypochlorite solutions. The peak region highlights where HOCl is most abundant and most effective as a disinfectant. This image includes extra operational detail on optimal pH ranges that goes slightly beyond OCR specification requirements but reinforces why controlled chlorination is important in water treatment. Source

A normal sentence is required here before any further definition or equation blocks, ensuring clarity and appropriate spacing within the notes.

Why Chlorine Is Used

Chlorine treatment provides several key benefits:

Effective microbial control: Kills bacteria, viruses, and pathogens responsible for waterborne diseases.

Residual effect: Residual chlorine remains in the water supply, continuously preventing contamination.

Low cost and scalable: Suitable for large municipal systems.

Oxidising power: Allows chlorine to act quickly and persistently across varying water conditions.

Residual chlorine: The small concentration of chlorine that remains in treated water to prevent recontamination during distribution.

Unlike alternative disinfectants such as ozone or UV, chlorine ensures continued protection long after treatment.

Risks and Hazards of Chlorination

Despite its benefits, chlorination poses important chemical and health considerations.

Formation of Harmful By-Products

Chlorine can react with naturally occurring organic compounds in raw water to form chlorinated hydrocarbons, including trihalomethanes (THMs). These are potentially carcinogenic and must be carefully regulated. Water treatment facilities therefore balance chlorine dosage to minimise the formation of these by-products.

Toxicity and Handling Concerns

Chlorine gas is highly toxic and corrosive:

Inhalation can cause respiratory damage.

Spills or leaks require immediate containment.

Storage cylinders must be rigorously maintained to avoid accidental release.

Water chemists must therefore weigh the microbial safety benefits against the chemical hazards of chlorine use.

Combining Effectiveness and Safety

Public health policy considers both the effectiveness of chlorine and the potential side effects of its use. UK water authorities operate under strict regulations to maintain chlorine concentrations at levels that ensure microbial protection without exceeding safe limits for by-product formation. Alternative disinfectants may supplement chlorine, but its residual action means it remains the predominant method of water treatment.

Analytical Chemistry: Testing Halide Ions

This subsubtopic also includes the qualitative analysis of halide ions, a key skill in OCR A-Level Chemistry practical work. Halide testing is used in water quality investigations, environmental chemistry, and other analytical contexts.

Identifying Halide Ions with Silver Nitrate

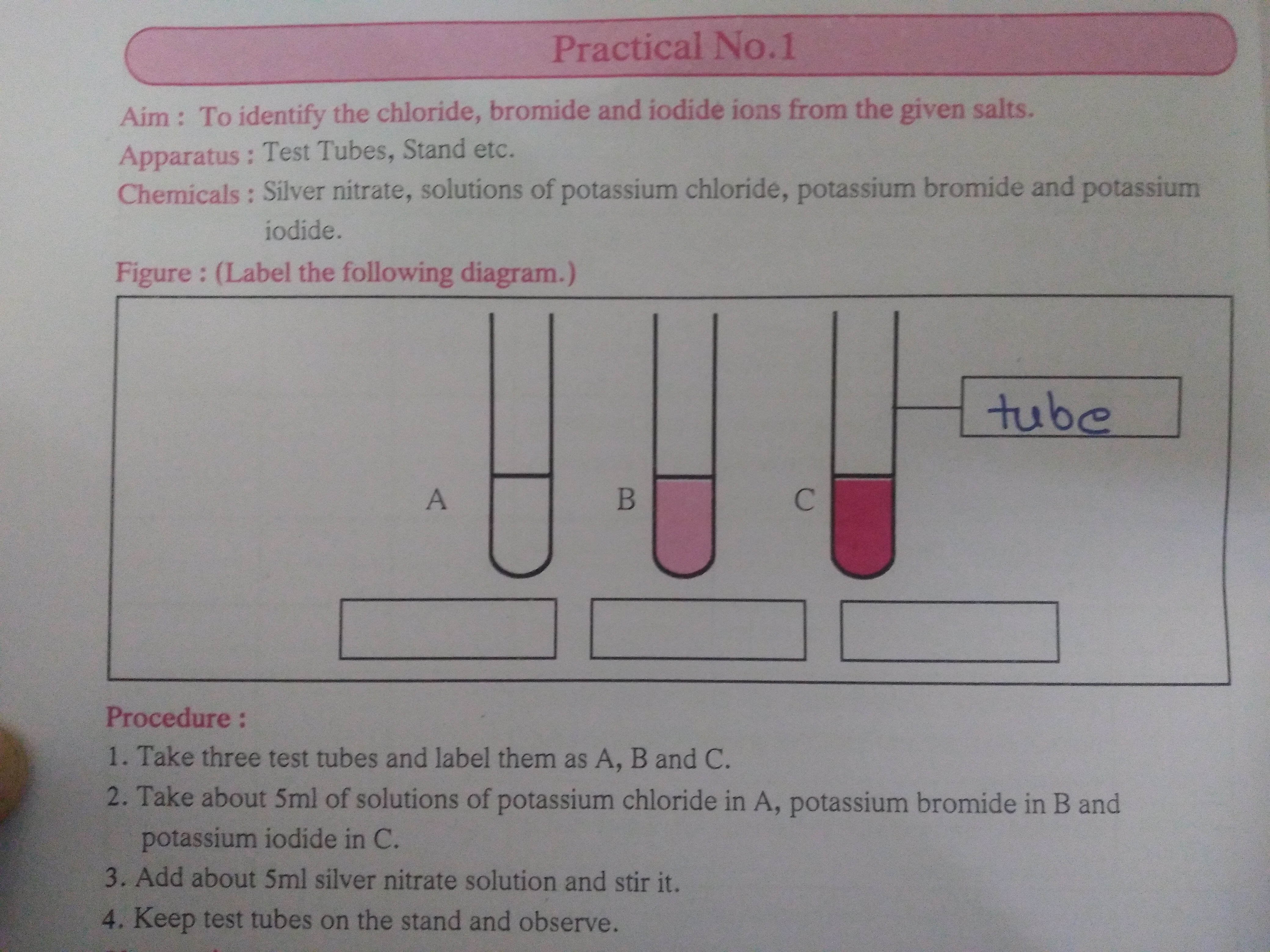

Halide ions—chloride, bromide and iodide—produce characteristic precipitates when reacted with aqueous silver ions (Ag⁺).

Halide ions: Negatively charged ions of Group 17 elements, including Cl⁻, Br⁻ and I⁻.

The identity of the halide ion can first be suggested from the colour of the silver halide precipitate formed with acidified silver nitrate solution.

Diagram showing the formation of silver chloride (white), silver bromide (cream or very pale yellow) and silver iodide (yellow) precipitates when silver nitrate is added to aqueous potassium chloride, potassium bromide and potassium iodide. This directly illustrates the colour changes used in the OCR test for halide ions. The diagram does not show the follow-up ammonia test, which is discussed in the text. Source

A normal sentence here ensures clear separation between definition and equation structures.

These colours arise from differences in the lattice enthalpies and solubility characteristics of the silver halides.

Distinguishing Halides Using Ammonia

Silver halide precipitates are treated with aqueous ammonia to differentiate them based on relative solubility:

Silver chloride dissolves in dilute ammonia.

Silver bromide dissolves only in concentrated ammonia.

Silver iodide is insoluble in ammonia, even when concentrated.

This two-step method—precipitation followed by ammonia treatment—is required by the OCR specification to identify halides accurately.

Linking Water Treatment and Halide Testing

Halide testing is important in water chemistry because halides can influence the behaviour of chlorine during treatment. Elevated halide levels may alter the types or quantities of by-products formed and affect monitoring strategies. Therefore, both the practical halide tests and the chemical understanding of chlorine’s behaviour are essential for evaluating treated water.

These notes provide the foundation to understand how chlorine ensures safe water supplies, the risks associated with its use, and how halides are detected through qualitative analysis.

FAQ

Chlorine forms both hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and hypochlorite ions (OCl⁻) in water, and their proportions depend strongly on pH.

At lower pH, a greater proportion of HOCl forms, which is a much stronger oxidising agent than OCl⁻. This increases microbial kill rates.

At higher pH, more OCl⁻ is present, reducing the overall oxidising power. Water treatment facilities therefore adjust pH to maintain optimum disinfectant strength.

THM formation depends on several conditions within the water:

Concentration of natural organic matter (NOM)

Temperature, with higher temperatures increasing by-product formation

Chlorine dose and contact time

pH, as alkaline conditions favour certain THM-forming pathways

Treatment plants often reduce NOM before chlorination to limit THM production.

Nitric acid removes other ions that may interfere by forming precipitates with silver ions.

It prevents the formation of silver carbonate or silver hydroxide, both of which would obscure the halide results.

Nitric acid is chosen because it does not introduce additional ions (such as chloride or sulfate) that would themselves react with silver ions.

Ammonia forms complex ions with silver ions, but the degree of formation varies between halides.

Silver chloride forms a stable complex in dilute ammonia.

Silver bromide dissolves only in concentrated ammonia as the equilibrium must be pushed further.

Silver iodide forms complexes too unstable to dissolve, even in concentrated ammonia.

These differences allow clear identification of halide ions.

Residual chlorine provides continued protection as water moves through pipes and storage systems.

It prevents microbial regrowth and contamination in distribution networks.

Maintaining residual levels also indicates whether the water is stable: low or absent residual chlorine may signal contamination, high organic load or treatment failure.

Practice Questions

Chlorine is added to drinking water during treatment.

Explain why chlorine is used, referring to its chemical behaviour in water.

(2 marks)

1 mark: Chlorine acts as a strong oxidising agent / kills bacteria and microorganisms.

1 mark: Chlorine reacts with water to form chloric(I) acid or hypochlorous acid, which is the active disinfectant species.

A sample of unknown water is tested for halide ions.

(a) Silver nitrate solution is added to the sample acidified with nitric acid. A yellow precipitate forms.

(b) The precipitate is then treated with both dilute and concentrated aqueous ammonia but does not dissolve.

(i) Identify the halide ion present.

(ii) Write the ionic equation for the formation of the precipitate.

(iii) Explain how the behaviour with ammonia confirms the identity of the halide ion.

(iv) State one potential risk associated with using chlorine in water treatment and link it to the relevant chemistry.

(5 marks)

(i) 1 mark: Iodide ion / I⁻.

(ii) 1 mark: Ag⁺(aq) + I⁻(aq) → AgI(s).

(iii) 2 marks:

1 mark: Silver iodide does not dissolve in either dilute or concentrated ammonia.

1 mark: This insolubility distinguishes iodide from chloride (dissolves in dilute ammonia) and bromide (dissolves in concentrated ammonia).

(iv) 1 mark: Any correct risk linked to appropriate chemistry, e.g.:

Chlorine can react with organic matter to form harmful chlorinated hydrocarbons such as trihalomethanes;

Chlorine gas is toxic or corrosive if inhaled or released accidentally.