OCR Specification focus:

‘Calculate energy change using q = mcΔT from calorimetry; discuss techniques and typical sources of error in measurements.’

Determining enthalpy changes experimentally allows chemists to quantify energy transfer in reactions using calorimetry. Accurate measurement, controlled conditions, and awareness of experimental limitations are essential for reliable enthalpy values.

Determining Enthalpy Changes Experimentally

Experimental determination of enthalpy changes centres on calorimetry, a technique used to measure temperature changes during chemical or physical processes. These temperature changes allow calculation of the energy transferred to or from the surroundings. Because enthalpy cannot be measured directly, calorimetry provides an indirect yet essential method for analysing thermochemical behaviour under controlled conditions. OCR requires students to understand how to apply q = mcΔT, identify suitable techniques, and evaluate common experimental errors that influence enthalpy values.

Key Principles of Calorimetry

Calorimetry involves measuring the temperature change of a known mass of material, often water or an aqueous solution, when a reaction occurs.

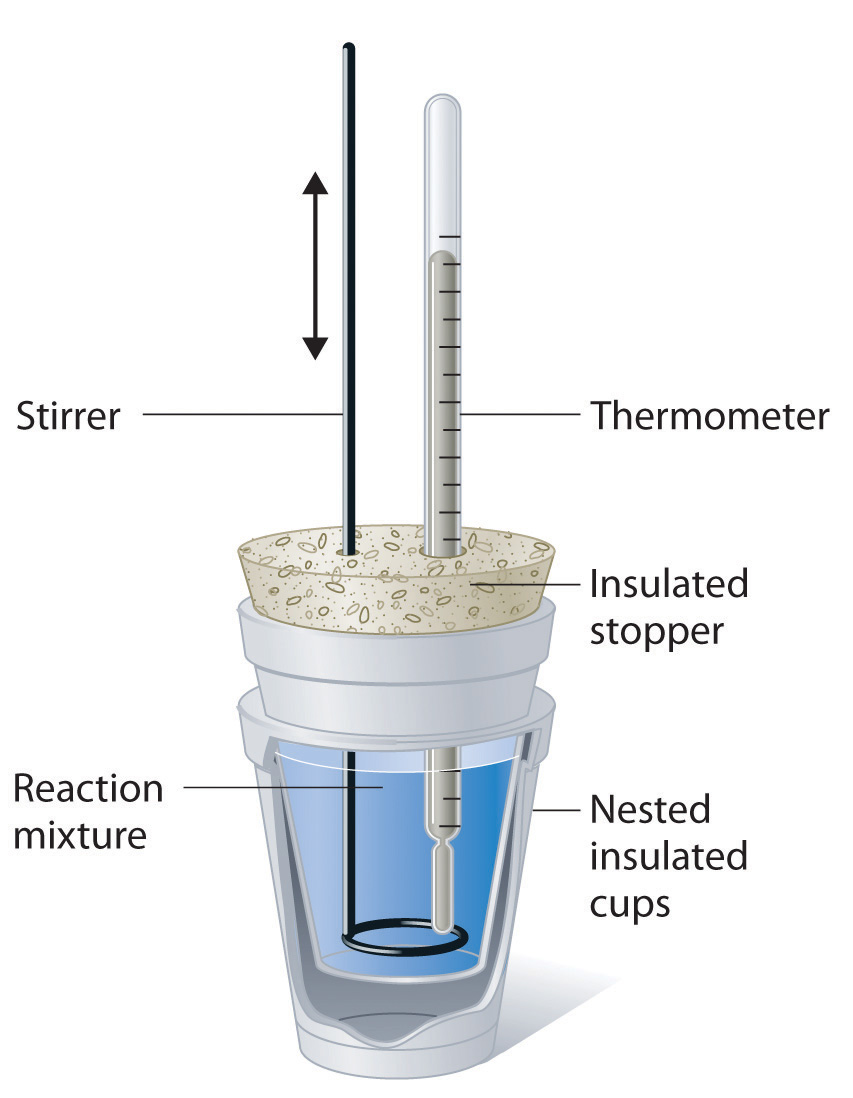

A coffee-cup calorimeter uses nested insulated cups, a lid, a thermometer and a stirrer to measure temperature changes in solution. The reaction mixture is contained inside the cups to reduce heat loss. This arrangement allows enthalpy changes of reactions in aqueous solution to be determined using the measured temperature change. Source

These temperature changes allow calculation of the energy transferred to or from the surroundings.

Energy Change (q) = mcΔT

m = mass of the substance being heated (g)

c = specific heat capacity (J g⁻¹ °C⁻¹)

ΔT = temperature change (°C)

In calorimetry, the surroundings are assumed to absorb all heat released or supplied by the reaction, though in practice some energy is inevitably lost. Accurate temperature measurement is therefore central to reliable enthalpy calculation.

Types of Calorimetry Used in OCR A-Level Chemistry

Different calorimetric setups are used depending on the reaction and desired measurement. Each method aims to maximise heat transfer to the measured substance while reducing losses to the environment.

Solution Calorimetry

This method is commonly used for reactions occurring in aqueous solution, such as neutralisation, dissolution, or displacement reactions.

Key features include:

A polystyrene cup or insulated vessel to minimise heat loss

Measurement of initial and final temperatures using a thermometer or probe

Stirring to ensure uniform temperature distribution

Because the reaction occurs within the solution, the mass used in the calculation corresponds to the total mass of the solution or water present.

Combustion Calorimetry

This method measures heat released when a fuel undergoes complete combustion.

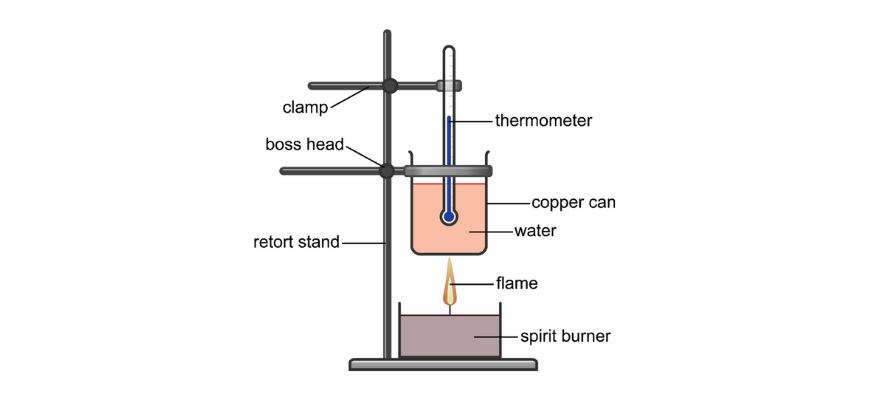

A combustion calorimeter consists of a spirit burner heating a copper can of water, with a thermometer to record the temperature rise. This setup demonstrates how heat from fuel combustion is transferred to water for enthalpy calculations. The image also highlights potential heat-loss pathways such as around the sides of the can. Source

A known mass of fuel is burned beneath a container of water.

Key aspects:

Burning takes place in open air or a simple spirit burner

The mass of fuel burned is recorded before and after heating

The temperature rise in the water is measured

Due to significant heat losses in open systems, experimental enthalpy values for combustion are typically less exothermic than data-book values.

Practical Techniques for Accurate Measurements

To produce reliable enthalpy data, careful experimental technique is essential. Students must be aware of best practices that reduce uncertainty.

Temperature Measurement and Control

Accurate temperature readings depend on appropriate measurement tools and consistent experimental handling.

Use digital temperature probes for higher precision when available

Allow the thermometer to equilibrate before recording readings

Measure temperatures at regular intervals, especially for reactions with slow heat release

Temperature extrapolation may sometimes be required to account for continued heat exchange after the reaction.

Minimising Heat Loss

Energy loss to the environment is one of the main limitations of school-level calorimetry.

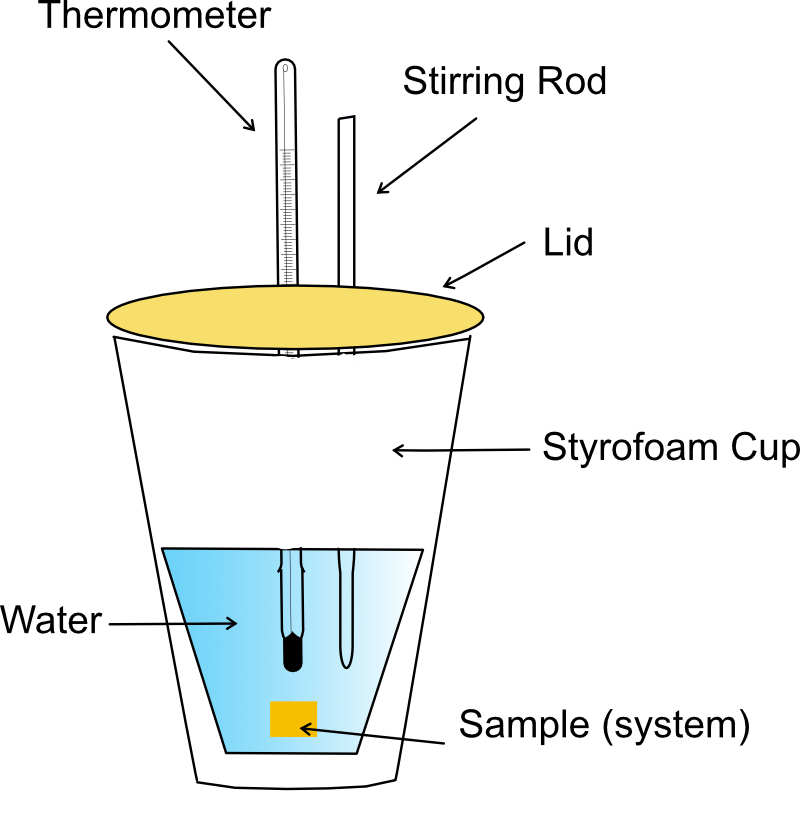

This diagram shows a styrofoam-cup calorimeter equipped with a lid, thermometer and stirring rod to reduce heat loss. The water inside acts as the measured surroundings absorbing energy from the system. The specific application to metal heat capacities extends beyond the OCR syllabus but illustrates the same calorimetric principles. Source

Strategies to reduce heat loss include:

Using lids or insulation around reaction vessels

Positioning the thermometer centrally and avoiding contact with vessel walls

Shielding combustion flames from draughts

Although these precautions improve accuracy, some heat loss is unavoidable.

Sources of Experimental Error

OCR requires discussion of typical errors that influence enthalpy measurements. These errors generally cause enthalpy values to appear less exothermic or less endothermic than expected.

Common sources of error include:

Heat loss to surroundings: The measured temperature change is smaller than the true value.

Incomplete combustion: Particularly relevant for fuels with lower volatility, producing soot and releasing less energy than theoretical values.

Evaporation of volatile substances: Loss of mass leads to inaccurate calculations, especially in combustion experiments.

Non-standard conditions: Temperature and pressure variations affect enthalpy but are not accounted for during basic calorimetry.

Assumption that specific heat capacity is constant: In practice, impurities or varying solution concentrations affect heat capacity.

Specific Heat Capacity: The energy required to raise the temperature of 1 g of a substance by 1 °C.

These limitations highlight why experimental values rarely match standard enthalpy changes listed in data books, which are measured under highly controlled conditions.

Improving Reliability and Precision

While perfect calorimetry is not possible in typical laboratory conditions, improvements can significantly enhance accuracy.

Useful improvements include:

Using calorimeters with improved insulation, such as copper vessels or commercial bomb calorimeters for combustion

Employing data-logging equipment to produce continuous temperature profiles

Ensuring complete reaction, particularly in displacement and neutralisation experiments

Using larger masses of water, reducing relative error in temperature measurement

Performing repeat trials and taking mean values to reduce random error

These refinements support more reliable enthalpy calculations and strengthen students’ understanding of thermochemical measurements.

Applying Calorimetry to Enthalpy Calculations

Once q = mcΔT is used to calculate the energy transferred, students convert this energy into an enthalpy change per mole of reactant. This requires:

Calculating moles of the limiting reagent

Adjusting the sign of ΔH: negative for exothermic, positive for endothermic processes

Scaling the value to per mole

Although calorimetry provides indirect measurements, it remains a foundational experimental technique for quantifying enthalpy changes in A-Level Chemistry.

FAQ

The main assumption is that all heat released or absorbed by the reaction is transferred to the measured substance, usually water or solution.

It is also assumed that the specific heat capacity remains constant throughout the temperature change, even though this can vary slightly with concentration or temperature.

Another assumption is that the reaction occurs instantaneously and reaches its maximum temperature without delay, which is rarely true in classroom experiments.

The precision of the thermometer determines how accurately small temperature changes can be recorded.

Digital temperature probes typically offer higher resolution and faster response times than traditional glass thermometers.

Slow-response thermometers can underestimate peak temperatures because the reaction may finish before the thermometer equilibrates fully.

In some reactions, especially slower neutralisations or dissolutions, heat continues to be lost while the temperature is still rising.

Plotting temperature against time allows a line of best fit to be extended back to the point of mixing, giving an estimate of the true maximum temperature.

This approach compensates for gradual heat loss and improves accuracy without altering equipment.

Larger masses of solution reduce the proportional effect of small measurement errors because a given heat loss produces a smaller change in temperature.

Using more solution also slows the rate at which the system cools, improving the accuracy of peak temperature readings.

However, excessive volume can dilute reactants, altering reaction rate or completeness, so it must be used carefully.

Effective insulation reduces heat flow between the calorimeter and its surroundings.

Factors influencing insulation include:

Material: polystyrene is preferred for its low thermal conductivity.

Surface area: smaller exposed surfaces reduce heat transfer.

Use of lids: covering the calorimeter reduces heat loss through convection.

Environmental conditions such as draughts or direct sunlight can also affect insulation performance.

Practice Questions

A student adds a known mass of zinc powder to 50.0 g of hydrochloric acid solution in a polystyrene cup. The temperature of the solution increases from 22.0 °C to 28.5 °C.

(a) State why a polystyrene cup is used in this experiment.

(b) Identify the surroundings in this calorimetry experiment.

(2 marks)

(a) 1 mark

To reduce heat loss to the surroundings / provide insulation.

(b) 1 mark

The surroundings are the solution (water/acid mixture) absorbing the heat released.

A student carries out an experiment to determine the enthalpy change of neutralisation between hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide using calorimetry.

The student records the temperature every 30 seconds and obtains the maximum temperature rise after mixing.

(a) State the equation used to calculate the energy change q.

(b) Explain why stirring the mixture improves the accuracy of the temperature measurement.

(c) Give two reasons why the experimentally determined enthalpy change is less exothermic than the data-book value.

(d) Suggest one improvement to the apparatus or method that would reduce heat loss.

(5 marks)

(a) 1 mark

q = mcΔT.

(b) 1 mark

Stirring ensures an even temperature throughout the solution / prevents temperature gradients.

(c) 2 marks (one mark each)

Accept any two:

Heat lost to surroundings (cup, air, thermometer).

Incomplete reaction or incomplete mixing.

Specific heat capacity assumed to be constant.

Temperature rise underestimated due to slow heat exchange.

(d) 1 mark

Accept any one:

Use a lid or additional insulation around the calorimeter.

Use a more insulated calorimeter (e.g., improved polystyrene cup).

Use a digital temperature probe to improve precision.