OCR Specification focus:

‘Interpret and use general, structural, displayed and skeletal formulae; select appropriate representation; recognise COOH and COO conventions and common ring symbols such as cyclohexane and benzene.’

Organic compounds can be represented using several formula types, each providing different structural information. Understanding these representations is essential for interpreting reactivity, structure, and relationships between organic molecules across the OCR course.

Representing Organic Formulae

Organic chemistry relies on multiple formula representations that convey varying levels of structural detail. OCR expects students to interpret and use these forms confidently, selecting the most appropriate representation for the context. This subsubtopic focuses on how to read and write general, structural, displayed, and skeletal formulae, and how standard conventions such as COOH, COO, and ring symbols are used to avoid ambiguity.

General Formulae

General formulae describe an entire homologous series, indicating the relationship between carbon, hydrogen, and other atoms. They do not show bonding but give a pattern applicable to all members of the series.

General Formula: A simplified algebraic expression showing the composition of all members of a homologous series.

General formulae are most useful when predicting the composition of related molecules or identifying trends across a series.

Structural Formulae

Structural formulae show how atoms are arranged in a molecule. OCR requires students to recognise both condensed and semi-condensed versions.

Structural Formula: A representation showing the arrangement of atoms in a molecule without displaying every bond explicitly.

These formulae provide clarity about connectivity while remaining compact, making them widely used for mid-detail representations.

Displayed Formulae

Displayed formulae show every atom and every bond, including lone pairs when required. They are used when bond-by-bond clarity is essential for discussing mechanisms or identifying features such as bond angles.

Displayed Formula: A detailed representation where all atoms and bonds are drawn explicitly to show the full structure.

Displayed formulae are especially helpful for visualising bonding and identifying functional groups.

Skeletal Formulae

Skeletal formulae are highly simplified representations used extensively in organic chemistry. OCR expects students to read and draw skeletal structures confidently.

Skeletal Formula: A representation using lines for carbon–carbon bonds, with carbon atoms at line ends and vertices, omitting hydrogen atoms attached to carbon.

Skeletal formulae highlight functional groups and carbon frameworks efficiently and are the preferred style for complex structures.

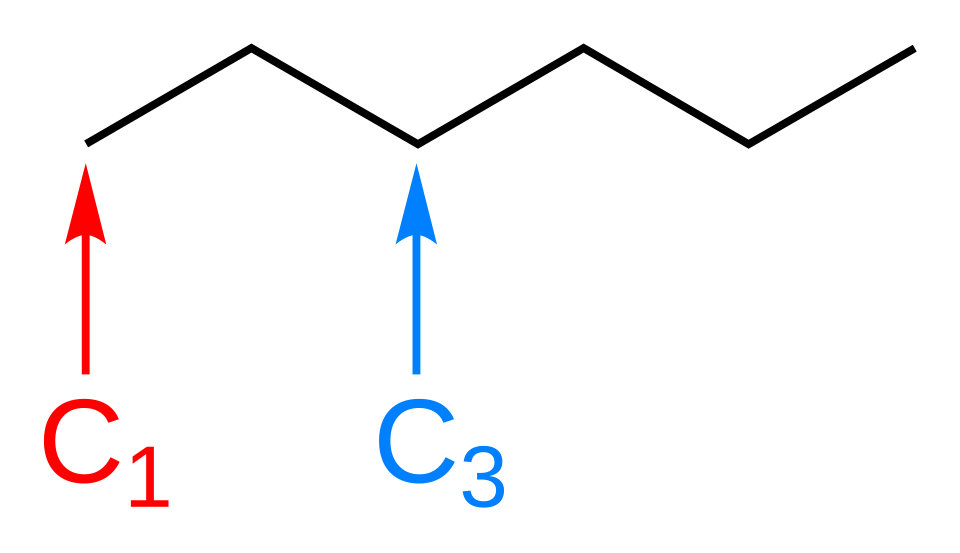

Skeletal formula of hexane, showing a six‑carbon chain as a zig‑zag line with selected carbons numbered. Each vertex represents a carbon atom with implied C–H bonds. This diagram focuses only on skeletal conventions and does not show other representation types. Source

Normal alkanes, aromatic compounds, and cyclic structures are often shown in skeletal form to reduce visual clutter and emphasise key structural features.

Conventions for COOH and COO Groups

OCR requires recognition of the shorthand conventions COOH (carboxylic acids) and COO (esters). These condensed forms avoid lengthy repeated structural detail.

COOH denotes a carboxylic acid containing a carbonyl and hydroxyl directly bonded to the same carbon.

COO is commonly used for an ester linkage, representing the carbonyl–oxygen–alkyl arrangement.

These conventions appear frequently in equations, mechanisms, and structural diagrams.

Representing Rings: Cyclohexane and Benzene

Students must recognise common ring symbols, particularly cyclohexane and benzene, which are often drawn in shorthand without explicit hydrogens.

Cyclohexane is typically shown as a hexagon with alternating single bonds implied.

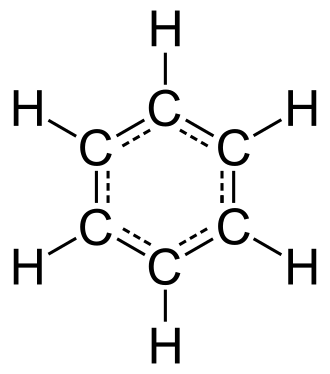

Benzene is represented either with a hexagon containing a circle to indicate a delocalised π-system or using alternating double bonds.

A benzene ring is usually drawn as a hexagon with a circle inside or with alternating double bonds, representing aromatic π-delocalisation.

Displayed structural formula of benzene, showing a six‑membered carbon ring with alternating C=C double bonds and one hydrogen attached to each carbon. This reinforces how aromatic rings can be represented explicitly, not just as a simple hexagon symbol. The image includes more detail than needed for skeletal shorthand but remains fully aligned with recognising benzene ring structures. Source

These conventions allow rapid identification of alicyclic and aromatic features.

Choosing the Appropriate Representation

The OCR specification emphasises selecting the appropriate representation depending on the task. Students should understand the advantages and limitations of each format.

When to Use Each Type

General formulae:

Identifying trends in a homologous series

Predicting molecular composition

Structural formulae:

Showing atom connectivity clearly

Distinguishing between structural isomers

Displayed formulae:

Demonstrating electron-pair movements in mechanisms

Visualising bonding and geometry

Skeletal formulae:

Presenting large or complex molecules concisely

Emphasising functional groups

Bullet-Point Summary of Key Skills Required by OCR

Students should be able to:

Interpret general, structural, displayed, and skeletal formulae in unfamiliar contexts.

Convert between different formula types accurately.

Recognise and reproduce COOH and COO conventions.

Identify cyclic structures such as cyclohexane and benzene in symbolic shorthand.

Use skeletal formulae to emphasise carbon frameworks and functional groups.

Distinguish clearly between hydrogens attached to carbon and those attached to heteroatoms.

Apply systematic representation choices to reduce ambiguity in organic structures.

Additional Important Terminology

Introducing key terminology early supports fluency when interpreting organic representations.

Functional Group: An atom or group of atoms responsible for the characteristic reactions of an organic molecule.

A brief understanding of functional groups is essential to interpreting formulae correctly, as their shapes and arrangements guide reactivity patterns.

Organic formula representations form a foundational language for the remainder of A-Level organic chemistry. Recognising, interpreting, and selecting representations accurately ensures that mechanisms, naming, and structural reasoning remain clear and consistent across the specification.

FAQ

Displayed formulae show all atoms and bonds, including individual C–H bonds. When converting to a skeletal formula, these hydrogen atoms on carbon are removed, and bond angles become generalised.

However, functional groups remain identifiable, and heteroatoms with attached hydrogens must still be written explicitly.

Look for characteristic shapes or letters:

A carbonyl (C=O) appears as a double bond to an O written at a line end or vertex.

An OH group appears as an O–H attached to the skeleton.

Rings appear as polygons; aromatic rings show alternating double bonds or a circle.

Pattern recognition becomes significantly faster with practice.

Condensed formulae keep mechanisms less cluttered, allowing focus on electron movement rather than full bond networks.

They also help when comparing similar molecules or showing repeating units, as they provide a compact representation that avoids unnecessary visual complexity.

Although basic skeletal formulae are flat, wedges and dashed wedges can be added to line structures to show 3D arrangements.

These symbols indicate bonds coming out of the plane (solid wedge) or going behind it (dashed wedge), allowing skeletal diagrams to represent stereochemistry clearly when needed.

Common errors include:

Forgetting that every line end or vertex represents a carbon atom.

Adding unnecessary hydrogens to carbon atoms.

Misplacing heteroatoms or omitting hydrogens on heteroatoms.

Checking carbon valency and adding hydrogens only to heteroatoms helps prevent these errors.

Practice Questions

Hexanoic acid is often represented using the condensed formula CH3(CH2)4COOH.

(a) State the functional group present in hexanoic acid.

(b) Name the type of formula used above.

(2 marks)

(a)

Carboxylic acid / COOH group (1 mark)

(b)

Condensed formula / structural formula (condensed) (1 mark)

The diagram below shows an unlabeled skeletal formula of an organic compound.

(a) State how many carbon atoms are present in the molecule.

(b) Redraw the molecule using a full displayed formula.

(c) Explain why skeletal formulae are often preferred when drawing larger organic molecules.

(d) Convert the displayed formula you drew into a structural formula using condensed notation.

(5 marks)

(a)

Correct count of carbon atoms from vertices and line ends (1 mark)

(b)

All atoms shown explicitly, including all C–H bonds (1 mark)

Correct connectivity matching the original skeletal structure (1 mark)

(c)

Award up to 2 marks:

Skeletal formulae reduce clutter or simplify complex structures (1 mark)

They allow rapid identification of functional groups and carbon frameworks (1 mark)

(d)

Correct condensed structural formula matching the displayed formula (1 mark)