OCR Specification focus:

'Specification information for this subsubtopic: Explain structural isomers as compounds with the same molecular formula but different structural formulae; deduce possible structures from a given molecular formula.'

Structural isomerism is a foundational idea in organic chemistry, helping explain how molecules with identical molecular formulae can differ in structure, properties, and chemical behaviour across homologous families.

Understanding Structural Isomerism

Structural isomerism arises when molecules share the same molecular formula but differ in the arrangement of atoms, giving rise to distinct structures and sometimes markedly different physical and chemical characteristics.

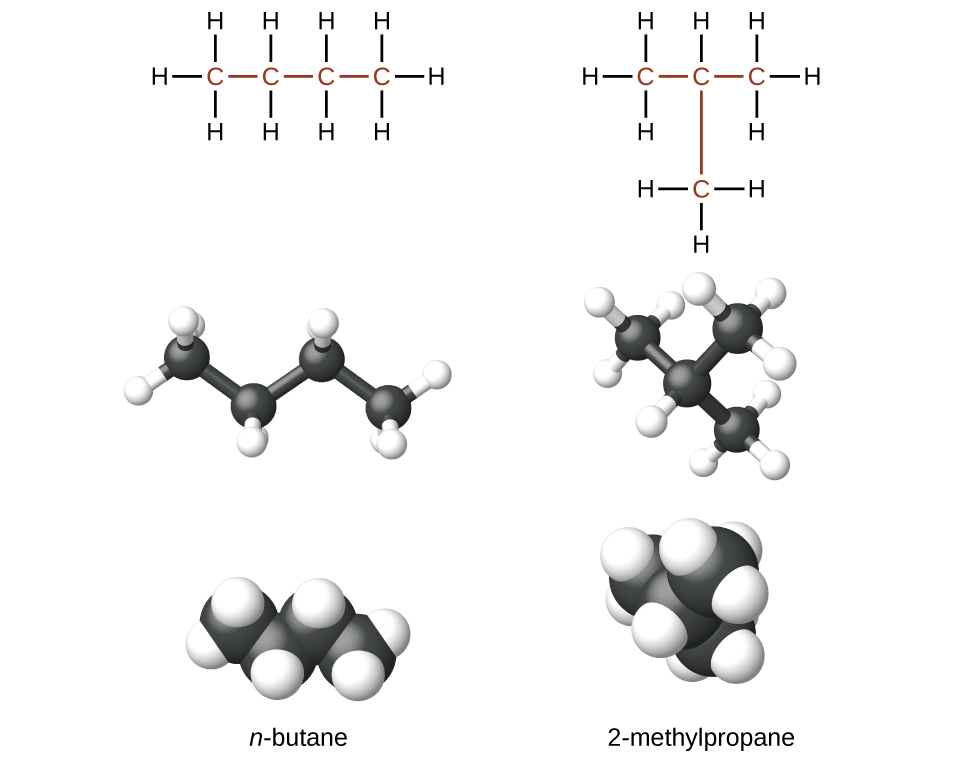

Isomers of butane illustrating how identical molecular formulae can produce different structures and 3D forms; includes additional model styles that extend slightly beyond syllabus needs. Source

Key Term: Structural Isomers

Structural isomers: Compounds that have the same molecular formula but different structural formulae.

Because many organic molecules consist of carbon frameworks capable of branching or incorporating different functional groups, multiple valid structures can often be derived from one molecular formula. This makes structural isomerism essential for analysing possible compounds in synthetic and mechanistic contexts.

Why Structural Isomerism Occurs

Carbon’s ability to form four covalent bonds arranged tetrahedrally and to generate long chains underpins the diversity of possible structures. Even small molecules can exhibit more than one structural arrangement, especially as carbon-chain length increases.

Types of Structural Isomerism

Although OCR focuses primarily on recognising and deducing structural isomers rather than naming every type, understanding the three core categories strengthens conceptual grasp and supports accurate structural prediction.

1. Chain Isomerism

Chain isomerism arises when the carbon skeleton differs between molecules sharing the same molecular formula. Higher members of homologous series often produce several chain isomers due to branching.

2. Positional Isomerism

Positional isomers have the same functional group but located in different positions on the carbon chain. This alters reactivity patterns, boiling points, and occasionally stability.

3. Functional Group Isomerism

Functional group isomers contain the same atoms arranged into different functional groups, leading to drastically different chemical properties. OCR specifications do not require memorising exhaustive examples, but knowing this category helps rationalise structural diversity.

Interpreting and Drawing Structural Formulae

To deduce structural isomers, students must confidently work with:

Structural formulae showing atom connectivity.

Displayed formulae illustrating all bonds.

Skeletal formulae especially useful for larger organic molecules.

A structural isomer must have a different arrangement of atoms; simply drawing a rotated or flipped form of the same molecule does not constitute isomerism.

Using Molecular Formulae to Deduce Isomers

The specification requires students to deduce possible structures from a given molecular formula. This process benefits from a systematic approach.

Approach for Deducing Isomers

Identify the number of carbons and consider possible chain arrangements.

Determine saturation by calculating the maximum number of hydrogens for alkanes (CnH₂ₙ₊₂) and comparing to the given formula.

Locate possible functional groups that match the molecular formula.

Generate variations by shifting functional groups along the chain where allowed.

Check each structure to ensure it is truly distinct and adheres to valency rules.

One sentence must appear here before any definition to comply with formatting rules.

Structural formula: A representation showing how atoms are arranged and connected within a molecule.

Structural formulae support systematic examination of potential isomers by explicitly mapping atom connectivity.

Impact of Structural Isomerism on Properties

Even small structural changes can produce significant differences in measurable properties. Key trends include:

Boiling and Melting Points

Increased branching typically lowers boiling points due to reduced surface contact and weaker London forces.

Straight-chain isomers often exhibit higher boiling points than their branched counterparts.

Chemical Reactivity

Changes in the position of a functional group can alter:

The reactive site within the molecule.

The reaction pathway, particularly in substitution or addition reactions.

The stability of intermediates, influencing mechanism outcomes.

These differences illustrate why structural isomerism plays a central role in analysing reaction mechanisms and predicting reactivity.

Representing Structural Isomers Effectively

Clear representation is essential for demonstrating understanding.

When Using Structural Formulae

Show all atoms and groups attached to each carbon.

Ensure correct valency, especially for carbon (four bonds).

Avoid redundancy—draw only genuinely distinct structures.

When Using Displayed Formulae

Depict all covalent bonds explicitly.

Show lone pairs only when relevant to the chemical context.

Display double and triple bonds clearly to distinguish saturation.

When Using Skeletal Formulae

Represent carbon chains efficiently using lines.

Recognise that end points and bends represent carbons.

Add functional groups explicitly to avoid ambiguity.

Recognising When Compounds Are Not Isomers

Students often mistake conformers or stereoisomers for structural isomers. OCR emphasises distinguishing these categories.

Compounds are not structural isomers if:

They differ only by rotation around single σ-bonds.

They are mirror images or differ by spatial arrangement only (stereoisomers).

They are identical structures drawn in different orientations.

Applying Specification Skills

The specification emphasises applying structural isomerism knowledge rather than memorising examples. Essential competencies include:

Skills Required

Correctly identify when compounds share a molecular formula.

Deduce all possible valid structural arrangements in line with bonding rules.

Interpret exam questions requiring sketches or recognition of structural variations.

Communicate structures clearly using appropriate formulae conventions.

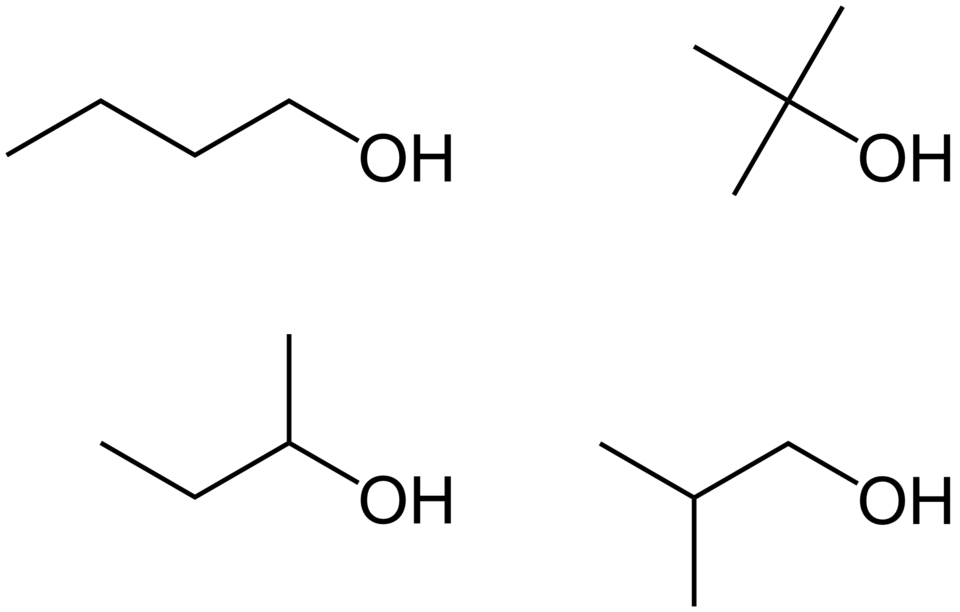

Isomers of butanol illustrating how varying chain structure and hydroxyl group position generates different molecules; includes primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohol representations beyond syllabus essentials. Source

These skills ensure students can fully meet the OCR requirement to “explain structural isomers as compounds with the same molecular formula but different structural formulae” and “deduce possible structures from a given molecular formula.”

FAQ

As the number of carbon atoms increases, the number of possible structural isomers rises rapidly because more branching patterns and positions for functional groups become available.

For example, while C4 hydrocarbons have only a few structural isomers, molecules with six or more carbons can form numerous chain and positional variations.

This expansion reflects carbon’s versatility in forming long, branched, and varied frameworks.

Rotation around a carbon–carbon single bond does not change the connectivity of atoms, only their orientation in space.

Structural isomers must differ in how atoms are joined, not in how a molecule is rotated or flipped. Rotations and reflections represent the same molecule and therefore do not count as new structural isomers.

A molecular formula can only generate functional group isomers if its atoms can be arranged into more than one valid functional group.

For example, C4H8O can produce an alcohol, aldehyde, ketone, or ester arrangement.

In contrast, some formulae lack the correct ratio of atoms (such as insufficient oxygens or hydrogens) to form alternative functional groups.

Structural isomers can show differences in several physical properties, including:

Density

Solubility

Optical clarity (where functional groups differ)

Vapour pressure

These variations arise because branching, functional group placement, and chain length affect intermolecular forces and molecular packing.

Skeletal formulae reduce visual clutter and emphasise carbon connectivity, making branching patterns easier to spot.

They help students quickly identify alternative arrangements because functional groups appear distinctly, and unnecessary hydrogen atoms are omitted.

This streamlined representation is particularly useful when deducing multiple possible structures from one molecular formula.

Practice Questions

Hexane (C6H14) has several structural isomers.

(a) State what is meant by the term structural isomers. (1 mark)

(b) Draw or describe one structural isomer of hexane other than hexane itself. (1 mark)

(2 marks)

(a)

Compounds with the same molecular formula but different structural formulae. (1)

(b)

Award one mark for any valid alternative structure, for example:

Branched chain such as 2-methylpentane or 3-methylpentane. (1)

Accept a correctly described structure or correct condensed/structural formula.

A compound has the molecular formula C4H8O.

(a) Deduce three different structural isomers that fit this molecular formula. (3 marks)

(b) Explain why these structures are considered structural isomers and not stereoisomers. (2 marks)

(5 marks)

(a) Award up to 3 marks for three correct, distinct structural isomers. Examples include:

Butanal

2-methylpropanal

Butan-2-ol

Butan-1-ol

Methyl propanoate

Any three valid structures = 3 marks.

(b)

They have the same molecular formula but different atom connectivity or functional group arrangement. (1)

They differ in structure rather than spatial arrangement; no stereochemical variation involved. (1)