OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe homolytic and heterolytic fission; define radicals and use dots for unpaired electrons; use curly arrows to show electron-pair movement and include relevant dipoles in mechanisms.’

Organic reactions often depend on how covalent bonds break and how electrons move. Understanding bond fission, radicals, and curly arrows is essential for interpreting mechanisms accurately and avoiding misconceptions.

Bond Fission in Organic Chemistry

Bond fission refers to the breaking of a covalent bond, and the way electrons are redistributed determines the type of reaction that follows. This subsubtopic focuses on homolytic fission, heterolytic fission, and the resulting species.

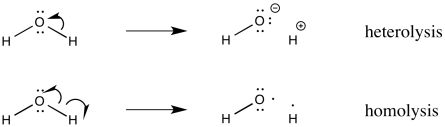

Homolytic Fission

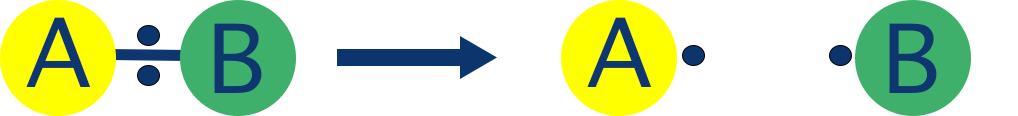

Homolytic fission occurs when a covalent bond breaks evenly, with one electron from the shared pair going to each atom. This produces two highly reactive radicals.

Radical: A species containing an unpaired electron, represented by a single dot. Radicals are extremely reactive due to electron deficiency.

Because both atoms retain one electron, this type of bond cleavage is most common under conditions such as UV light where energy input is sufficient to split the bond symmetrically. Homolytic fission underpins mechanisms such as radical substitution in halogenation.

Heterolytic Fission

Heterolytic bond fission occurs when both electrons from a covalent bond move to one atom only. This produces a pair of oppositely charged ions: a cation and an anion.

Heterolytic fission: Bond breaking in which both electrons move to one atom, forming ions rather than radicals.

A sentence explaining polarity is important here. In a polar bond such as C–Cl, the chlorine atom withdraws electron density more strongly, making heterolytic cleavage more likely.

This diagram compares heterolytic and homolytic bond fission using curved and fishhook arrows to illustrate electron movement and resulting species. Source

Radicals and Their Role in Organic Mechanisms

Radicals drive many chain reactions in organic chemistry, especially those requiring energy input. They are key intermediates in reactions involving homolytic fission.

Formation and Representation of Radicals

Radicals form when bonds undergo homolytic cleavage. They are always shown with a single dot, indicating the location of the unpaired electron. This notation is essential for tracking how radicals interact with other species in mechanisms.

Radical reactions typically involve three conceptual stages:

Initiation – homolytic fission generates radicals

Propagation – radicals react to produce new radicals, sustaining the chain

Termination – two radicals combine, removing radicals from the reaction mixture

These stages illustrate why radicals are short-lived yet highly influential reactive species.

This diagram illustrates homolytic fission of a covalent bond, producing two radicals represented with unpaired electron dots, consistent with OCR notation requirements. Source

Curly Arrows in Organic Mechanisms

Curly arrows are the essential symbolic tool for representing electron-pair movement in reaction mechanisms. OCR requires students to “use curly arrows to show electron-pair movement and include relevant dipoles,” which means recognising not only where the electrons go but also why they move in that direction.

Curly Arrow Conventions

A curly arrow always shows the movement of an electron pair, never a single electron. Arrow tails begin at the electron source and point toward the electron destination.

Curly arrow: A mechanism symbol showing the movement of an electron pair, starting where the electrons originate and pointing to where they move.

This contrasts with radical mechanisms, which sometimes use single-headed arrows (not required at this stage of the OCR course) to depict single-electron movement. The arrows used in this subsubtopic focus exclusively on electron-pair motion, consistent with heterolytic processes.

Understanding arrow origins is vital. For example, the tail of the arrow may begin at a lone pair, a bond, or a negative charge, depending on where the electrons start.

Dipoles and the Direction of Curly Arrows

Since heterolytic fission often results from differences in electronegativity, mechanisms must show partial charges (δ+ and δ–) to explain electron movement. Curly arrows will always move towards δ+ regions because electrons are attracted to electron-poor centres.

Key features include:

Electronegativity differences generate dipoles

Electron-pair movement is always from electron-rich to electron-poor sites

Positive centres (δ+) attract electron pairs during bond formation

Negative centres (δ–) can donate electron pairs in mechanisms

Including dipoles ensures that electron movement is chemically justified rather than arbitrary.

Mechanistic Context of Bond Fission and Curly Arrows

Bond fission types directly influence how mechanisms are drawn. Heterolytic fission is central to electrophilic addition, nucleophilic substitution, and elimination reactions because these processes depend on ions and electron-pair flow. In contrast, homolytic fission is associated with free radical mechanisms and requires significantly different conditions.

Linking Bond Fission to Reaction Pathways

Students should be able to determine which bond fission type applies based on:

Bond polarity

Reaction conditions (heat, UV, catalysts)

Nature of the products (ions vs radicals)

Mechanism type (ionic vs radical)

These considerations ensure mechanisms are drawn accurately and electron flow is logical.

Organic reactions rely on the redistribution of electrons, and understanding the contrast between heterolytic and homolytic fission supports deeper comprehension of mechanism diagrams.

Importance of Showing Electron Flow Accurately

Curly arrows do not show atom movement; they show electron movement. Misplacing curly arrows leads to chemically impossible steps. Students should remember:

The arrow must begin at an electron source

The arrow must end at a bond or atom gaining electron density

Mechanisms should clearly show bond formation or bond breaking

Dipoles must be included when relevant to explain arrow direction

Accuracy in these diagrams is essential for predicting reactivity, identifying intermediates, and understanding overall reaction transformations.

This subsubtopic emphasises the foundational skill of representing electron movement clearly and logically, which becomes crucial across later organic chemistry topics.

FAQ

Homolytic fission typically requires high-energy conditions, particularly UV radiation, because both atoms must receive enough energy to take one electron each.

Heterolytic fission is favoured under polar conditions, such as in the presence of polar solvents, which stabilise ions formed by uneven electron distribution.

Overall, factors that stabilise radicals promote homolysis, while those that stabilise ions promote heterolysis.

Radicals contain an unpaired electron, making them highly unstable. They quickly combine with other species to achieve electron pairing.

Radicals tend to undergo:

propagation steps that form new radicals, or

termination steps where two radicals collide

Because each radical seeks a more stable electron configuration, they rarely persist for long under reaction conditions.

The key factor is bond polarity. A polar bond, where one atom is significantly more electronegative, predisposes the shared electron pair to move entirely toward that atom.

Other factors favouring heterolysis include:

the ability of the resulting ions to be stabilised by resonance

the presence of polar or protic solvents

neighbouring group effects that stabilise cations or anions

Fishhook arrows show the movement of a single electron rather than an electron pair. They accurately represent radical processes such as propagation steps.

OCR restricts this subsubtopic to curly arrows (full-headed arrows) because the focus is on mechanisms involving electron-pair movement, particularly heterolytic fission. Radical mechanisms involving fishhook arrows are taught later, once foundational fission concepts are secure.

Curly arrows always move from electron-rich to electron-poor areas. Dipoles identify these regions by indicating which atom bears partial negative charge and which bears partial positive charge.

A δ– atom pulls electron density towards itself, while a δ+ atom is susceptible to electron attack.

This ensures curly arrows are placed logically, reflecting actual electron movement rather than arbitrary diagram choices.

Practice Questions

Explain the difference between homolytic fission and heterolytic fission.

(2 marks)

1 mark for each correct distinction:

Homolytic fission: the bond breaks evenly, with one electron going to each atom, forming two radicals.

Heterolytic fission: the bond breaks unevenly, with both electrons going to one atom, forming a cation and an anion.

(Allow reverse order.)

The diagram below represents part of an organic mechanism.

Curly arrows are used to show electron movement during heterolytic bond breaking.

(a) Describe what a curly arrow represents in an organic mechanism. (1)

(b) Explain why curly arrows always start at a lone pair, a bond, or a negative charge. (2)

(c) State what types of species are formed when a polar C–X bond undergoes heterolytic fission, and explain why this occurs. (2)

(5 marks)

(a) 1 mark

A curly arrow shows the movement of an electron pair.

(b) Up to 2 marks

The tail of the arrow must start at an electron source.

Lone pairs, bonds, or negative charges contain electron pairs that can move.

(c) Up to 2 marks

Heterolytic fission of a polar C–X bond forms a cation and an anion. (1)

The more electronegative atom takes both electrons because it attracts electrons more strongly. (1)

(Allow clear equivalent wording.)