OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain tetrahedral shape and approximately 109.5° bond angle around each carbon in alkanes using electron pair repulsion; be able to draw 3D representations.’

Alkanes exhibit characteristic three-dimensional shapes governed by electron-pair repulsion around each carbon atom. Understanding these shapes and associated bond angles is essential for predicting physical behaviour and reactivity patterns.

Shapes and Bond Angles in Alkanes

Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons containing only C–C and C–H σ-bonds. The spatial arrangement of these bonds is not arbitrary; instead, it is dictated by the repulsion between electron pairs around each carbon atom. According to electron-pair repulsion principles, bonding pairs adopt positions that maximise separation, producing the tetrahedral geometry associated with approximately 109.5° bond angles.

Tetrahedral geometry: The three-dimensional arrangement formed when four electron pairs around a central atom repel equally, resulting in bond angles close to 109.5°.

This predictable geometry underpins much of alkane chemistry, influencing physical properties such as boiling points and the conformations molecules may adopt.

The Role of σ-Bonds in Determining Shape

A σ-bond is formed by the direct overlap of orbitals along the internuclear axis. In alkanes, every C–C and C–H bond is a σ-bond, and these bonds allow full rotation around the C–C axis. The freedom of rotation does not alter the fundamental tetrahedral arrangement around each carbon; instead, it creates different conformations while maintaining consistent bond angles.

σ-bond: A covalent bond formed by direct orbital overlap along the axis between two nuclei, allowing free rotation.

Because each carbon in an alkane forms four σ-bonds, the electron pairs arrange themselves as far apart as possible, enforcing tetrahedral geometry.

Electron Pair Repulsion and Bond Angles

The approximate 109.5° bond angle in alkanes arises from the repulsion between bonding electron pairs. According to electron-pair repulsion theory, electron density regions seek maximum separation to minimise repulsive forces.

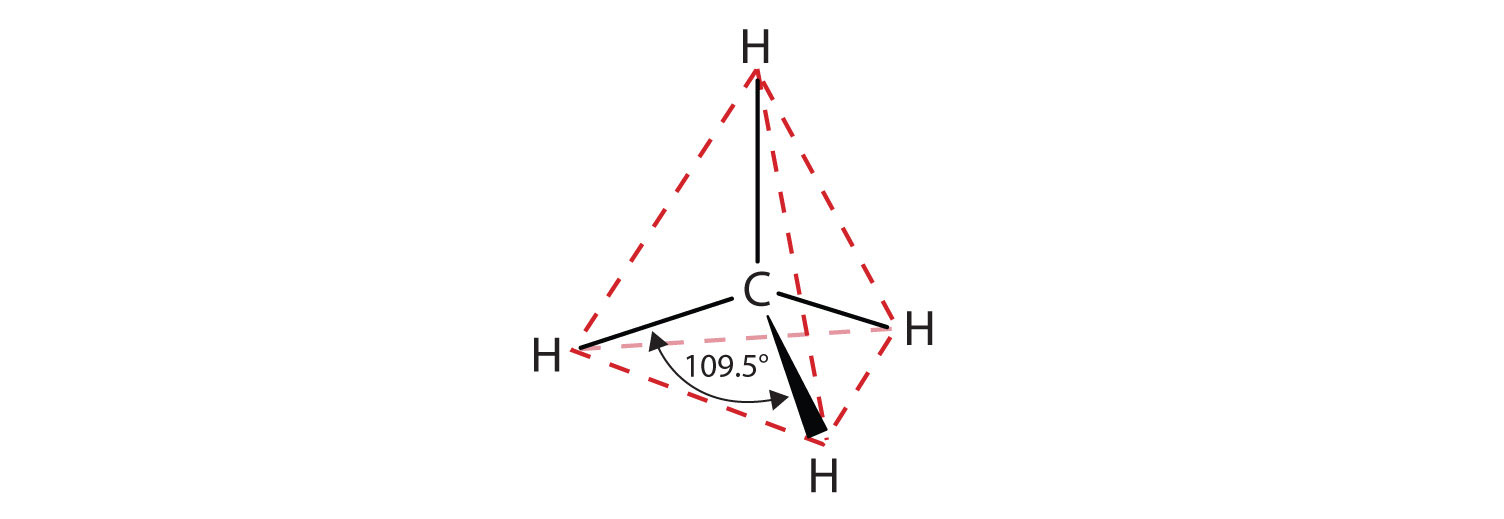

Tetrahedral arrangement of bonds around a carbon atom in methane, showing the H–C–H bond angle of about 109.5°. The wedge and dashed bonds represent bonds projecting out of and into the plane. The red dashed outline is an additional visual aid not required by OCR but helps highlight the tetrahedral geometry. Source

This produces a shape where each bond is evenly spaced in three dimensions.

Bond angle: The angle formed between two covalent bonds originating from the same central atom.

Even small deviations from 109.5° can influence the stability or steric environment of a molecule, but in standard alkanes the bond angle remains consistent due to uniform σ-bonding.

Three-Dimensional Representations of Alkanes

OCR expects students to “be able to draw 3D representations”, which requires familiarity with conventions used to depict tetrahedral structures. These conventions aim to communicate spatial orientation clearly.

Common 3D drawing conventions include:

Solid wedge: A bond projecting out of the plane towards the viewer.

Dashed wedge: A bond projecting behind the plane away from the viewer.

Straight line: A bond lying in the plane of the page.

By combining these symbols, students can accurately depict the tetrahedral arrangement around each carbon atom. For instance, methane, the simplest alkane, shows one bond using a solid wedge, one using a dashed wedge, and two using straight lines, illustrating its three-dimensional shape even on a flat page.

Tetrahedral Geometry Across Alkane Chains

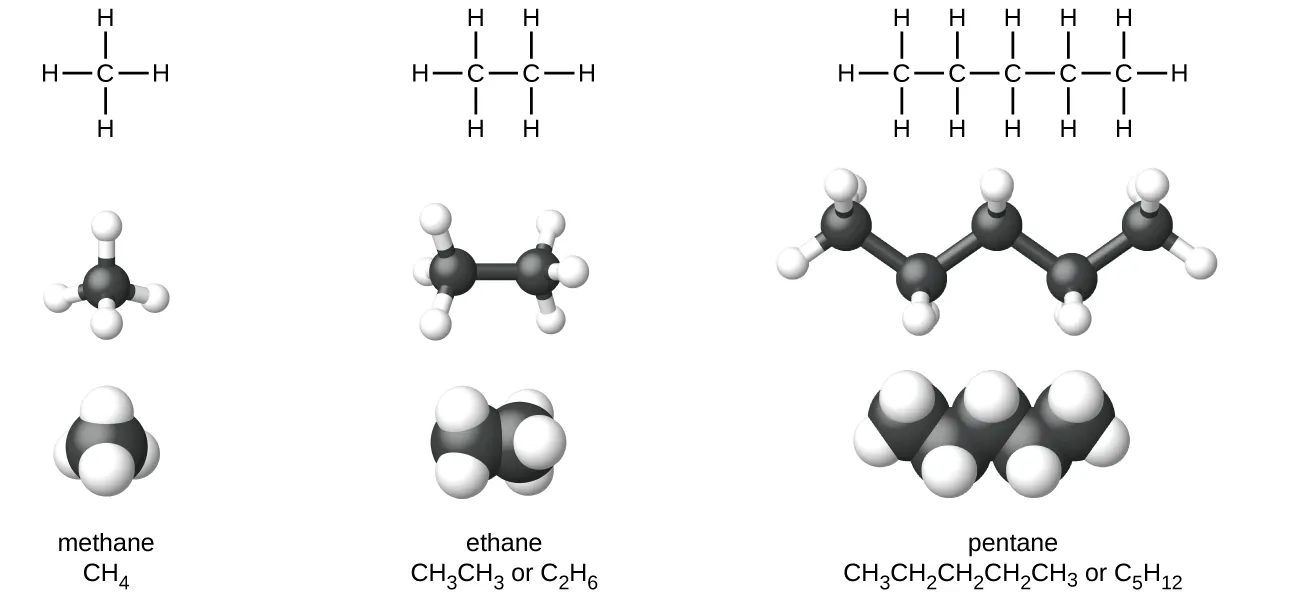

The tetrahedral shape applies consistently across all alkanes, from methane to long-chain hydrocarbons. Each carbon maintains four electron-dense bonding regions, leading to:

Consistent bond angles (~109.5°)

Three-dimensional zig-zag chains rather than straight, flat structures

Conformational flexibility arising from rotation around σ-bonds

These structural features contribute to differences in boiling points, surface area, and molecular packing—although such trends fall beyond this specific subsubtopic, they rely fundamentally on shape and bond angle considerations.

Lewis structures, ball-and-stick models and space-filling models of methane, ethane and pentane. The pentane models demonstrate how tetrahedral carbons generate the characteristic zigzag chain. Naming and formula labels provide helpful context but exceed the specific OCR focus on shape and angles. Source

Why the Tetrahedral Angle Is ~109.5°

A tetrahedral arrangement is the geometry that provides maximum separation between four electron pairs in three-dimensional space. The resulting bond angle of approximately 109.5° is larger than the angles possible in trigonal planar (120° but only three groups) or linear geometries (180° but only two groups). With four bonding pairs, tetrahedral geometry gives the lowest overall electron-pair repulsion, making it the energetically preferred configuration for alkane carbons.

Although slight variations may arise due to substituent effects or strain in ring structures, simple acyclic alkanes maintain this ideal tetrahedral geometry at every carbon.

Visualising Bond Angles in Larger Alkanes

In extended chains, tetrahedral geometry produces the characteristic zig-zag shape due to alternating carbon orientations. Each C–C bond links two tetrahedral centres; thus, the molecule bends at each carbon. This arrangement enhances spatial efficiency and stability.

Students should be aware that while the C–C–C bond angle remains close to 109.5°, the overall structure is not circular or planar but an extended 3D chain.

Importance of Bond Angles in Understanding Reactivity

Although alkanes are relatively unreactive, their shapes and bond angles still influence how they interact with other species. For example:

Steric hindrance increases with branching due to three-dimensional crowding.

Conformational changes can affect access to certain hydrogen atoms during reactions.

Molecular flexibility impacts physical behaviour such as intermolecular interactions.

While these ideas link to other areas of the course, shape and bond angle form the foundational structural context needed for deeper discussion later.

Summary of Key Points on Shapes and Bond Angles

Alkanes contain four σ-bonds around each carbon.

Electron-pair repulsion forces these bonds into a tetrahedral geometry.

The bond angle around each carbon is approximately 109.5°.

Students must be able to draw accurate 3D representations using wedge–dash notation.

Tetrahedral geometry produces the zig-zag carbon chain shape observed in alkanes.

FAQ

Substituents with different sizes or electronegativities can slightly compress or expand the ideal 109.5° tetrahedral angle. Larger groups introduce steric repulsion, widening adjacent angles, while highly electronegative atoms draw electron density closer, narrowing the angles opposite them.

These shifts are small but measurable and can influence stability and molecular shape in more complex organic structures.

A straight-line arrangement would force carbon atoms into unrealistic bond angles or electron-pair proximity. The zigzag orientation allows each carbon to maintain its tetrahedral geometry without strain.

Rotation around sigma bonds permits minor conformational changes, but the lowest-energy form consistently follows this zigzag pattern.

Cyclic alkanes try to maintain the 109.5° tetrahedral angle, but ring size restricts this. Smaller rings, such as cyclopropane and cyclobutane, experience significant angle strain because their internal angles are far from ideal.

Larger rings better approximate tetrahedral geometry and therefore exhibit lower strain.

Branching increases the density of substituents around a carbon, altering local spatial arrangements. Although each carbon still attempts to maintain tetrahedral geometry, increased crowding can compress some angles and expand others.

Highly branched alkanes also become more compact, reducing surface area and affecting physical properties such as boiling point.

The tetrahedral shape distributes electron pairs so they are as far apart as possible in three dimensions. This minimises repulsion, giving the configuration its low-energy, high-stability characteristics.

Other geometries cannot achieve equal spatial separation for four bonding regions, making tetrahedral the preferred structure for carbon in alkanes.

Practice Questions

Explain why the bond angle around each carbon atom in an alkane is approximately 109.5°.

(1–3 marks)

Bonding electron pairs around each carbon repel each other equally. (1 mark)

Repulsion is minimised when the four pairs adopt a tetrahedral arrangement. (1 mark)

Tetrahedral arrangement results in bond angles of approximately 109.5°. (1 mark)

Figure 1 shows a three-dimensional representation of an alkane fragment.

(a) State the name of the 3D drawing convention used to represent the bonds in Figure 1.

(b) Describe how electron-pair repulsion theory accounts for the overall three-dimensional shape of the carbon chain.

(c) Explain why alkanes can rotate around C–C bonds but still maintain their characteristic shape.

(4–6 marks)

(a)

Wedge-and-dash (or wedge-bond) notation. (1 mark)

(b)

Each carbon has four bonding pairs of electrons. (1 mark)

These electron pairs repel to positions of maximum separation. (1 mark)

This leads to a tetrahedral arrangement around each carbon atom. (1 mark)

(c)

C–C bonds in alkanes are sigma bonds formed by direct orbital overlap along the internuclear axis. (1 mark)

Sigma bonds allow free rotation. (1 mark)

Rotation changes conformations but does not alter the tetrahedral bond angles, so the overall 3D zigzag shape is maintained. (1 mark)