OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain low reactivity of alkanes by high σ-bond enthalpies and very low bond polarity; connect microscopic bonding to macroscopic inertness.’

Alkanes exhibit notably low chemical reactivity owing to their strong σ-bonds and extremely weak bond polarity, resulting in limited interactions with most reagents under normal conditions.

Low Reactivity of Alkanes: Core Concepts

Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons containing only C–C and C–H σ-bonds, and understanding why they are largely inert requires linking molecular bonding to macroscopic behaviour. Two microscopic features dominate: high σ-bond enthalpies and very low bond polarity. These characteristics limit opportunities for bond attack or rearrangement, making alkanes generally unreactive except under specific, often extreme, conditions such as combustion or radical substitution initiated by ultraviolet radiation.

The Role of Strong σ-Bonds

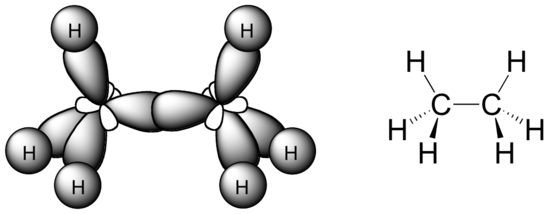

The σ-bonds in alkanes arise from direct, end-on overlap of orbitals, producing highly stable and low-energy bonding interactions. Because σ-bonds concentrate electron density directly along the internuclear axis, breaking them requires considerable energy input.

Bond enthalpy: The energy required to break one mole of a specified bond in the gaseous state.

In alkanes, every C–C and C–H bond is a σ-bond, formed by end-on overlap between orbitals on the bonded atoms.

A diagram of the ethane molecule showing sp³–sp³ and sp³–1s orbital overlaps forming strong σ‑bonds. The visual highlights the tetrahedral arrangement around carbon atoms in saturated hydrocarbons. Source

C–C and C–H σ-bonds have high bond enthalpies, meaning they resist homolytic or heterolytic cleavage. This stability limits reaction pathways that depend on the availability of weaker or more easily polarised bonds. The lack of significant strain or reactive functional groups further reduces the likelihood of spontaneous reactions, even when alkanes are exposed to moderately reactive species.

Lack of Bond Polarity and Its Consequences

Reactivity in organic chemistry often depends on the presence of polar bonds, which create partial charges that guide electrophiles and nucleophiles toward specific reaction sites. In alkanes, however, both carbon and hydrogen have similar electronegativities, resulting in very low bond polarity. This lack of charge separation makes alkanes unattractive targets for electron-rich or electron-poor reagents.

Electronegativity: The ability of an atom to attract electrons in a covalent bond.

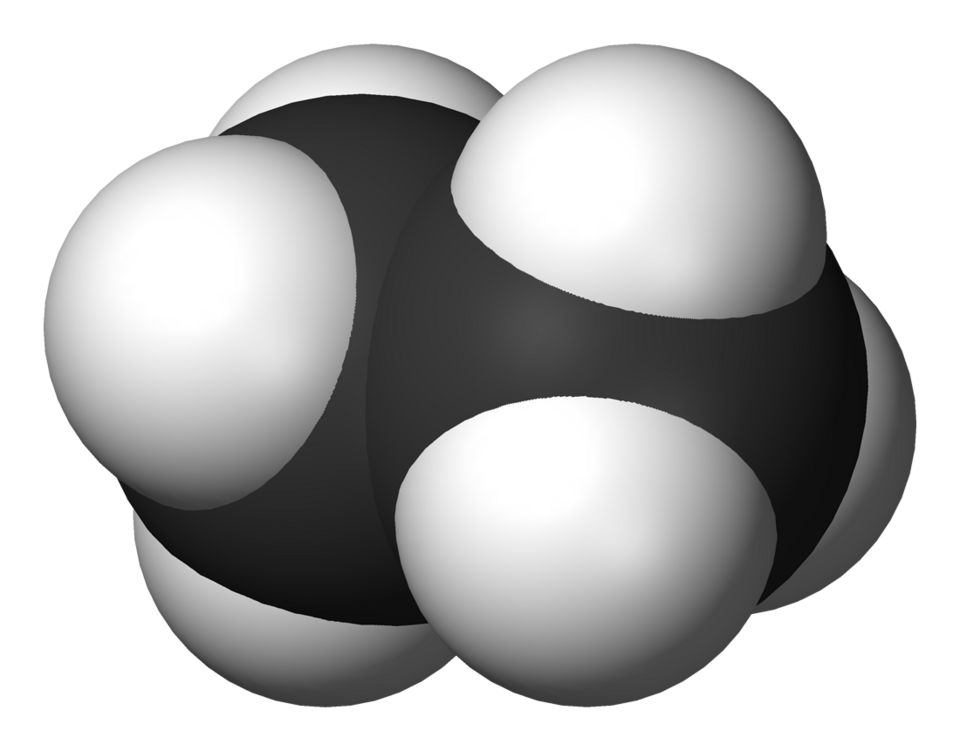

The tetrahedral arrangement of these σ-bonds around each carbon atom spreads electron density evenly, so there are no strongly positive or negative regions in an alkane molecule.

A space‑filling model of ethane illustrating its uniform electron distribution and lack of polar regions. This reinforces the concept that alkanes are non‑polar and chemically unreactive toward polar reagents. Source

Because alkanes do not exhibit significant polarisation, reagents cannot easily distinguish between carbon atoms or identify regions of electron density suited for attack. This uniformity explains why alkanes do not undergo reactions such as electrophilic addition, nucleophilic substitution, or nucleophilic addition under standard conditions. Their general inertness is therefore rooted in both bond strength and electronic symmetry.

A brief gap exists between these two factors and the macroscopic behaviour of alkanes, which manifests as low chemical reactivity in laboratory and industrial contexts.

Connecting Microscopic Bonding to Macroscopic Inertness

Alkanes’ persistent stability can be understood by examining how molecular structure influences observable behaviour. Their combination of strong σ-bonds and minimal polarity yields several consequences that directly produce their characteristic low reactivity.

Limited Interaction with Electrophiles and Nucleophiles

Most common organic reactions involve electrophiles (electron-pair acceptors) or nucleophiles (electron-pair donors). Without polar bonds or electron-rich functional groups, alkanes fail to offer suitable reaction sites.

Electrophiles cannot locate regions of significant electron density.

Nucleophiles find no partially positive carbon centres to attack.

Transition states requiring polarisation are not stabilised.

As a result, reactions typical of alkenes, carbonyls, or halogenoalkanes do not occur.

Resistance to Mechanistic Pathways

Many organic mechanisms rely on induced dipoles, resonance stabilisation, or heterolytic bond cleavage. Because alkanes lack these features, they resist mechanistic processes such as:

Electrophilic addition — requires a polarised multiple bond.

Electrophilic substitution — requires a delocalised aromatic ring.

Nucleophilic substitution — requires a polar C–X bond (where X is typically a halogen).

Nucleophilic addition — requires a polar π-bond, usually in carbonyl groups.

This selectivity helps explain why alkanes are often used as inert solvents in laboratory experiments where reactivity must be minimised.

Energy Considerations in Reactivity

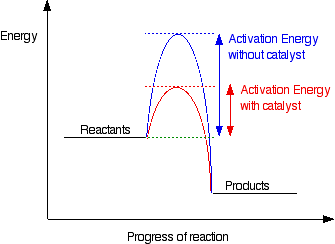

High σ-bond enthalpies make bond cleavage energetically demanding. Even when reagents could theoretically attack an alkane, the activation energy for the process is prohibitively high.

Activation energy: The minimum energy required to begin a chemical reaction by enabling bond breaking or bond formation.

To react, an alkane molecule must reach a high activation energy so that at least one strong σ-bond can be broken during a collision with another particle.

An energy profile diagram illustrating the activation energy barrier that must be overcome for a reaction to proceed. The catalysed pathway shown is additional information beyond the syllabus but remains standard A‑Level context. Source

Because activation energies are so large, alkanes generally do not react at room temperature or under mild heating. Only under vigorous conditions—such as combustion or UV-initiated radical processes—can enough energy be supplied to overcome these barriers.

When Alkanes Do React: Conditions Needed

Although alkanes are largely inert, certain reactions do occur under specific circumstances. These reactions highlight the underlying reasons for low reactivity by demonstrating the need for extreme conditions.

High-Temperature Combustion

Alkanes burn exothermically in excess oxygen, but the initiation of combustion requires a spark or flame to supply sufficient energy to break initial σ-bonds. Once started, the reaction becomes self-sustaining due to heat released from new bond formation in CO₂ and H₂O.

Radical Substitution under UV Light

In the presence of halogens and ultraviolet light, alkanes undergo radical substitution, a mechanism dependent on homolytic bond fission. UV radiation provides the required energy to generate radicals, enabling a reaction pathway that bypasses the need for polarity or low bond enthalpy.

Initiation: Homolytic fission forms radicals.

Propagation: Radicals react with alkanes to generate new radicals.

Termination: Radicals combine, ending the chain process.

These highly specific conditions reinforce the idea that alkanes are unreactive unless substantial energy is supplied or radical pathways become available.

Summary of Key Factors Behind Low Reactivity

High σ-bond enthalpy makes bond breaking energetically demanding.

Very low bond polarity prevents electrophiles and nucleophiles from targeting the molecule.

Lack of functional groups limits accessible reaction pathways.

High activation energies restrict reactions under normal laboratory conditions.

FAQ

Heterolytic fission requires a polar bond so that one atom can take both electrons. Alkanes have extremely weakly polar C–C and C–H bonds, offering no natural direction for electron movement.

Stronger σ-bonds also make heterolytic cleavage energetically unfavourable, so such reactions typically require harsh conditions or do not occur at all.

Alkanes possess repetitive C–C and C–H bonding, creating a uniform electron distribution and minimal variation in reactive sites.

Because every carbon atom in a straight-chain alkane experiences a similar local environment, reagents cannot select a preferred carbon for attack, reducing specificity and reactivity.

Their non-polar nature means they do not interact strongly with reactants or catalysts. This prevents interference with polar or charged intermediates.

Alkanes also have relatively stable boiling points, making them practical for controlled-temperature reactions.

Cycloalkanes may contain angle strain or torsional strain, which weakens bonds and increases reactivity relative to open-chain alkanes.

Straight-chain alkanes lack such strain, keeping σ-bonds at ideal tetrahedral angles and maximising stability.

UV radiation supplies energy sufficient to induce homolytic fission, generating radicals that can initiate chain reactions.

This bypasses the need for polarity or electrophilic attack, providing a unique pathway for alkane reactivity not available under normal thermal conditions.

Practice Questions

Explain why alkanes are generally unreactive towards electrophiles.

(2 marks)

1 mark each for any of the following, up to 2 marks:

Alkanes contain C–C and C–H bonds that have very low polarity, so electrophiles are not attracted to them.

There are no regions of high electron density in alkanes for electrophiles to attack.

Alkanes show very low reactivity under standard laboratory conditions.

Discuss the microscopic bonding features responsible for this low reactivity and explain how these features link to the macroscopic behaviour of alkanes.

Your answer should refer to bond enthalpies, bond polarity and activation energy.

(5 marks)

Award marks for the following points, up to 5 marks:

States that alkanes have strong σ-bonds with high bond enthalpies, making bond breaking energetically difficult (1 mark).

Recognises that C–C and C–H bonds are almost non-polar due to similar electronegativities of carbon and hydrogen (1 mark).

Explains that the absence of polarity means electrophiles and nucleophiles cannot easily identify reactive sites (1 mark).

States that high activation energy is required to initiate reactions because of strong σ-bonds and lack of polarisation (1 mark).

Links these microscopic features to observed macroscopic inertness, e.g., alkanes do not react readily unless exposed to UV light or high temperatures (1 mark).