OCR Specification focus:

‘Define electrophile as an electron-pair acceptor; show electrophilic addition mechanisms with curly arrows and relevant dipoles; apply Markownikoff’s rule via carbocation stability trends.’

Alkenes undergo characteristic reactions based on the presence of a π-bond, which is more reactive than a σ-bond, allowing addition reactions with species that accept electron pairs. This section explores the nature of electrophiles, how electrophilic addition proceeds, and why Markownikoff’s rule governs product distribution in unsymmetrical additions.

Introduction

Electrophilic addition arises from alkene π-bond reactivity, enabling electron-pair-accepting species to attack the C=C bond. Mechanisms rely on curly arrows, dipoles, and carbocation stability.

Electrophiles and the Reactivity of the C=C Bond

Alkenes contain both a σ-bond and a π-bond within the C=C double bond, with the π-bond positioned above and below the plane of the carbon atoms. The π-electrons are more exposed, making the bond the primary site of attack by species attracted to electron density.

When discussing reaction mechanisms, an electrophile must be clearly defined because it is central to understanding the entire process.

Electrophile: A species that accepts an electron pair.

The definition highlights that electrophiles are electron-pair acceptors, contrasting with nucleophiles, which donate electron pairs. Electrophiles may be positively charged (e.g. H⁺), polar molecules with δ⁺ regions, or molecules that become polarised in the presence of an alkene.

The π-bond breaks during the reaction, allowing two new σ-bonds to form, which stabilises the molecule. Because σ-bonds have higher enthalpy than π-bonds, the process is energetically favourable. Curly arrows are used to show electron-pair movement from the π-bond towards the electrophile, illustrating the bond-forming step.

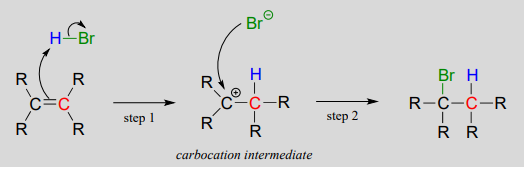

Electrophilic addition of HBr to an alkene proceeds through protonation forming a carbocation, followed by attack from Br⁻. Curly arrows show electron movement in each step. The diagram labels electrophile and nucleophile roles clearly. Source

Curly Arrows and Relevant Dipoles in Electrophilic Addition

The OCR specification requires students to show curly arrows, meaning arrows must originate from electron pairs or bonds and point towards electron-deficient centres. It is also necessary to show relevant dipoles, which often form when a non-polar halogen approaches the alkene.

Why Dipoles Form

Alkenes induce temporary dipoles in halogen molecules because the approaching π-electrons repel the halogen’s electron cloud. This generates a δ⁺–δ⁻ separation, making the molecule momentarily electrophilic.

Essential Mechanistic Features

Students should recognise the following features in an electrophilic addition mechanism:

The curly arrow from the π-bond to the electrophile

A dipole shown on the attacking molecule when appropriate

Formation of a carbocation intermediate

Attack of the intermediate by a negative ion

Final formation of an addition product with two new σ-bonds

Because electrophilic addition always involves electron-pair movement, curly arrows must be placed precisely to show correct mechanistic flow.

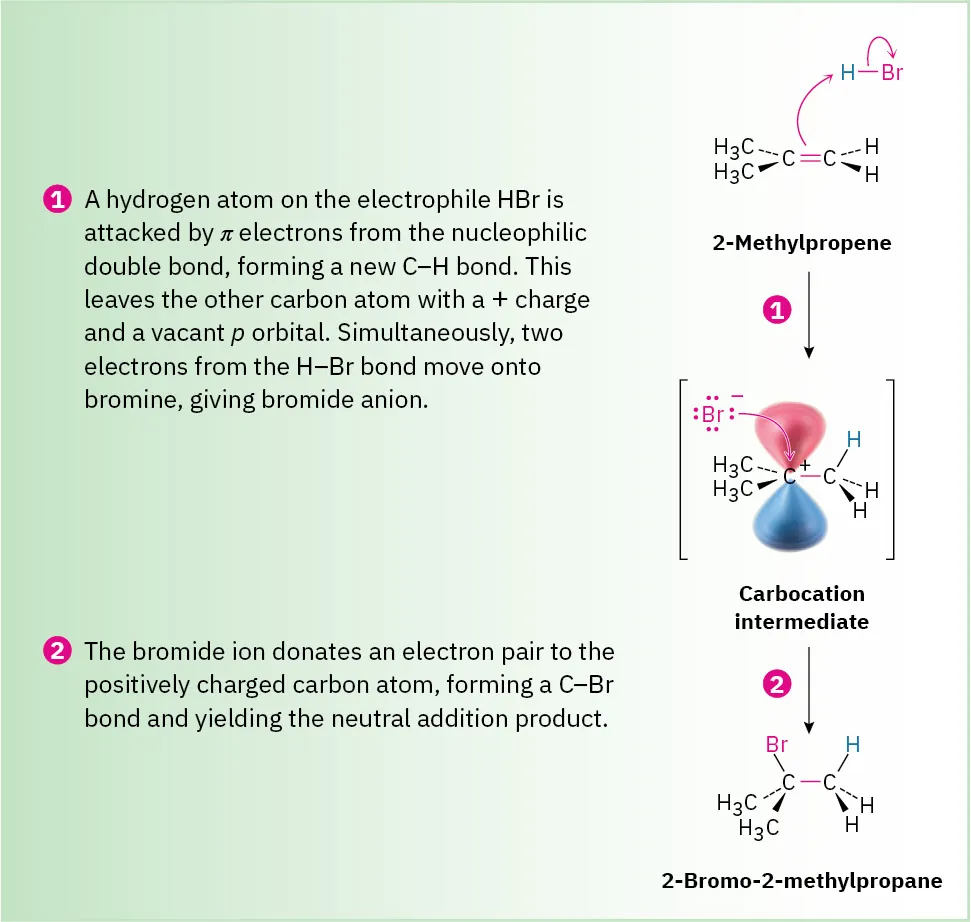

Formation of the Carbocation Intermediate

During electrophilic attack, one carbon of the double bond forms a new bond to the electrophile. This step breaks the π-bond and generates a carbocation, a positively charged carbon species.

Carbocation: An ion containing a positively charged carbon atom.

A carbocation’s stability determines which product forms most readily.

This mechanism shows protonation of the alkene to produce a tertiary carbocation, followed by nucleophilic attack from Br⁻. Curly arrows illustrate all electron-pair movements. The figure aligns with OCR requirements for depicting stepwise electrophilic addition. Source

Markownikoff’s Rule and Carbocation Stability

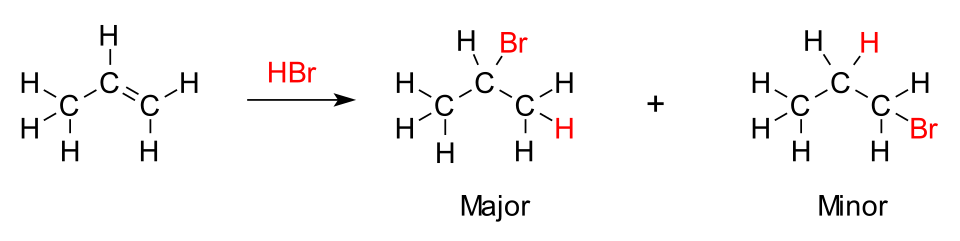

Markownikoff’s rule provides a predictable outcome when an unsymmetrical electrophile, such as HX, adds across an unsymmetrical alkene. The rule states that the hydrogen atom bonds to the carbon with the greater number of hydrogen atoms already attached, while the halide bonds to the more substituted carbon.

Markownikoff’s rule: In electrophilic addition of HX to an unsymmetrical alkene, the H attaches to the carbon with more hydrogens, forming the more stable carbocation.

This rule reflects the underlying principle of carbocation stability.

The image demonstrates Markovnikov addition of HBr to propene, with H bonding to the carbon already bearing more hydrogens and Br attaching to the more substituted carbon. This reflects formation of the more stable secondary carbocation. The figure remains focused strictly on regiochemistry relevant to the syllabus. Source

The major product always forms via the more stable carbocation intermediate, because its lower energy leads to a faster, more favourable pathway.

A typical mechanism therefore includes:

Initial electrophilic attack forming the most stable carbocation

Subsequent attack by the halide ion (X⁻)

Production of a haloalkane following addition across the former C=C bond

The specification emphasises that students should apply Markownikoff’s rule using carbocation stability trends, rather than memorising product structures without reasoning.

Electrophilic Addition Mechanisms: Key Steps

Although different electrophiles participate in electrophilic addition, the underlying pattern remains consistent. Students must be able to represent and explain these steps clearly.

Stepwise Process

Electrophile approaches the alkene, forming or possessing a δ⁺ centre

Curly arrow from the π-bond moves towards the electrophile

Break in the electrophile’s bond (e.g., H–X) forming ions

Carbocation intermediate forms on the more substituted carbon

Nucleophilic attack by the negative ion on the carbocation

Formation of the addition product, containing two new σ-bonds

Importance of Electron Flow

Accurate curly arrows and correct placement of charges ensure the mechanism reflects electron movement realistically. These conventions are essential for communicating organic processes in a standardised, scientific format.

Electrophilic Addition in the OCR Context

The OCR specification requires fluency with:

Identifying and defining electrophiles

Recognising dipoles and polarisation

Drawing complete mechanisms

Showing curly arrows precisely

Applying Markownikoff’s rule with carbocation stability

Relating electron movement to observed products

Understanding these mechanistic principles prepares students to analyse and predict outcomes for a wide range of electrophilic addition reactions encountered throughout organic chemistry.

FAQ

Electrophile strength depends on how electron-deficient the reactive centre is. Species with a full positive charge, such as H+, are generally stronger electrophiles than polar molecules with only a partial positive charge.

Halogen molecules become stronger electrophiles when highly polarised, either naturally or through interaction with the alkene’s π-electrons.

A weaker bond within the electrophile, such as the H–Br bond compared with H–Cl, can also increase reactivity because it breaks more easily during addition.

Markownikoff’s rule applies only when the mechanism proceeds through a carbocation intermediate. If a different mechanism operates, such as a concerted process, the regiochemistry may not follow the rule.

Additions involving peroxide-induced radical mechanisms also bypass carbocation formation, causing anti-Markownikoff products to dominate.

Alkenes with symmetrical environments also show no Markownikoff preference because both carbons of the C=C bond behave identically.

Polar protic solvents stabilise carbocations, often accelerating steps involving carbocation intermediates. They can also solvate anions, influencing the likelihood of nucleophilic attack.

Non-polar solvents may slow the reaction by providing less stabilisation to ionic species.

In some additions, the solvent can act as a nucleophile if sufficiently reactive, producing an alternative addition product.

The approach of the alkene’s π-electrons repels the electron cloud in the halogen molecule, producing an instantaneous dipole. Larger halogen atoms polarise more easily because their electron clouds are more diffuse.

The distance between the alkene and halogen, the temperature, and the alkene’s electron density all influence how readily this dipole forms.

Rearrangements occur when a carbocation intermediate shifts to form a more stable carbocation, typically through hydride or alkyl shifts.

Rearrangements alter the position of the positive charge, allowing nucleophilic attack at a different carbon and producing a structural isomer of the expected product.

These processes occur only when the rearranged carbocation is significantly more stable than the initially formed carbocation.

Practice Questions

Define the term electrophile and explain why alkenes react readily with electrophiles.

(2 marks)

1 mark: Electrophile defined as an electron-pair acceptor.

1 mark: Explanation that alkenes react readily because the π-bond is electron-rich and attracts electrophiles.

Hydrogen bromide reacts with propene to form a mixture of products.

(a) Describe the mechanism for this reaction, including all curly arrows and intermediate species.

(b) Explain why the major product forms according to Markownikoff’s rule.

(5 marks)

(a) Mechanism (3 marks total)

1 mark: Curly arrow from the C=C π-bond to the hydrogen atom of HBr.

1 mark: Correct formation of the carbocation intermediate (secondary carbocation on the middle carbon).

1 mark: Curly arrow from Br⁻ to the carbocation to form the product.

(b) Explanation of Markownikoff’s rule (2 marks total)

1 mark: Hydrogen adds to the carbon already bonded to more hydrogens.

1 mark: This forms the more stable carbocation intermediate (secondary more stable than primary), leading to the major product.