OCR Specification focus:

‘Deduce repeat units from monomers and vice versa; discuss benefits and issues of processing waste polymers, including energy recovery, feedstock use, detoxification, and biodegradable/photodegradable alternatives.’

Alkenes form addition polymers through reactions of their C=C bonds, creating long-chain molecules central to modern materials. Their environmental impact requires understanding polymer formation, waste processing and sustainability strategies.

Addition Polymers and Repeat Units

Addition polymers form when many alkene molecules, known as monomers, add together without the loss of small molecules. The polymer backbone consists of saturated C–C bonds, giving stability and chemical resistance. This stability contributes to durability but also to persistence in the environment, making polymer waste management an essential topic in modern chemistry.

Identifying Monomers and Repeat Units

Students must be able to deduce a polymer’s repeat unit and identify the monomer from which it is formed.

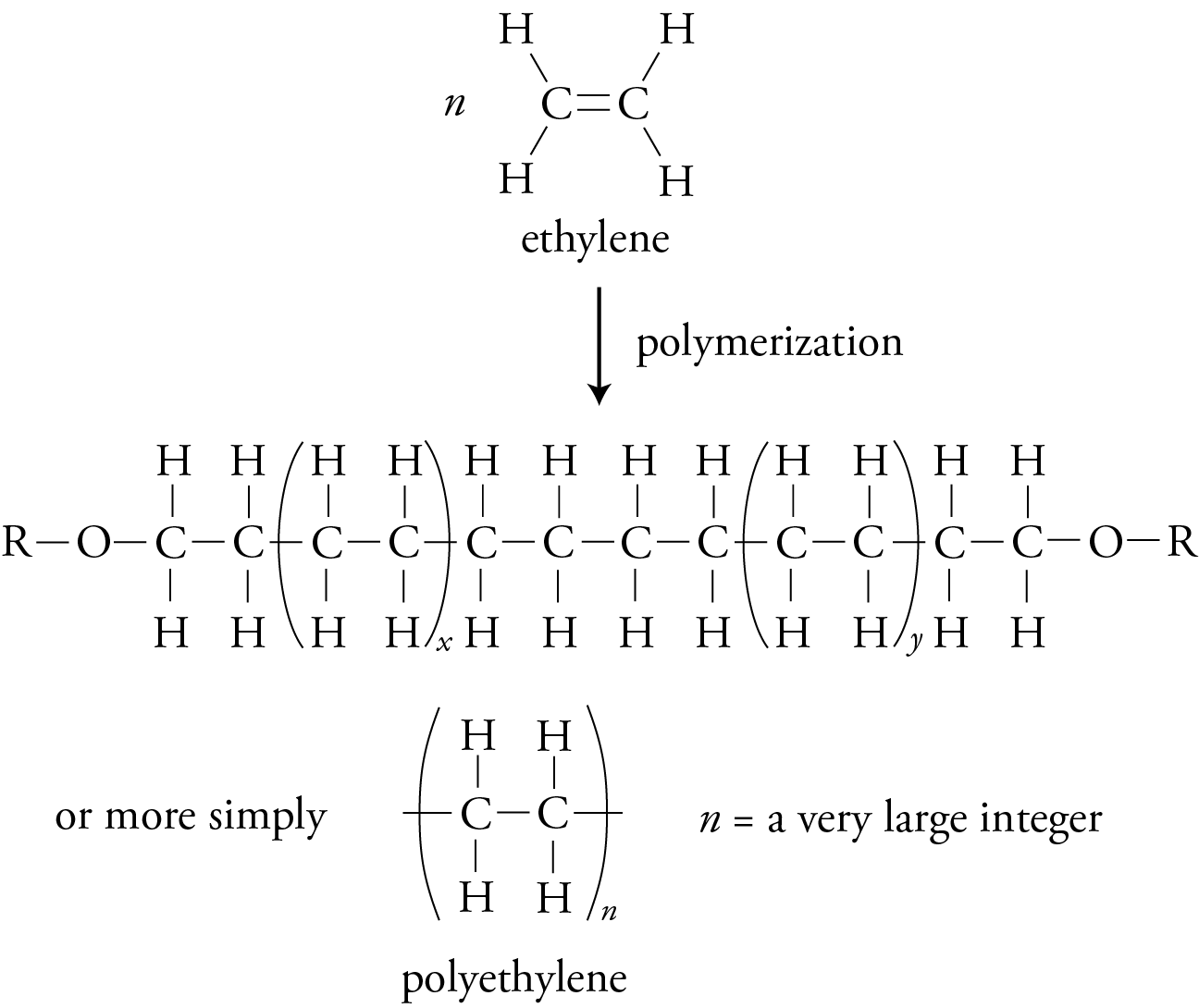

Diagram of the addition polymerisation of ethene to form poly(ethene), showing monomers, repeat unit brackets and the use of n to indicate many repeating units. This visual reinforces how a simple alkene forms a long-chain polymer. The image contains no extra detail beyond the A-Level requirement for recognising monomer–polymer relationships. Source

The repeat unit is the smallest structural segment of a polymer chain that recurs along its length. Recognising this link between structure and reactivity is key to understanding how a polymer's properties arise from its molecular architecture.

Repeat unit: The smallest section of a polymer that repeats along the entire chain and represents the arrangement originating from the monomer.

A polymer’s repeat unit is typically shown in square brackets with an “n” to indicate a large number of repeating segments. When deducing monomers from a polymer, the process involves identifying where the C=C bond would have been present before polymerisation. This requires careful examination of the polymer backbone to locate the original unsaturated carbon atoms. A brief normal sentence must follow to ensure clarity before any further formal definition.

Polymerisation from Alkenes

Addition polymerisation involves breaking the π-bond of the alkene monomer and forming new σ-bonds between carbon atoms. The mechanism is not required at this level for all polymers, but understanding that the driving force is the reactivity of the π-bond is essential. Common polymers arising from this process include poly(ethene), poly(propene), poly(chloroethene) and polystyrene, each displaying characteristic physical properties linked to the monomer structure.

Sustainability Challenges and Waste Polymer Processing

Waste polymer disposal is a major environmental issue due to the chemical inertness and long degradation times of synthetic polymers.

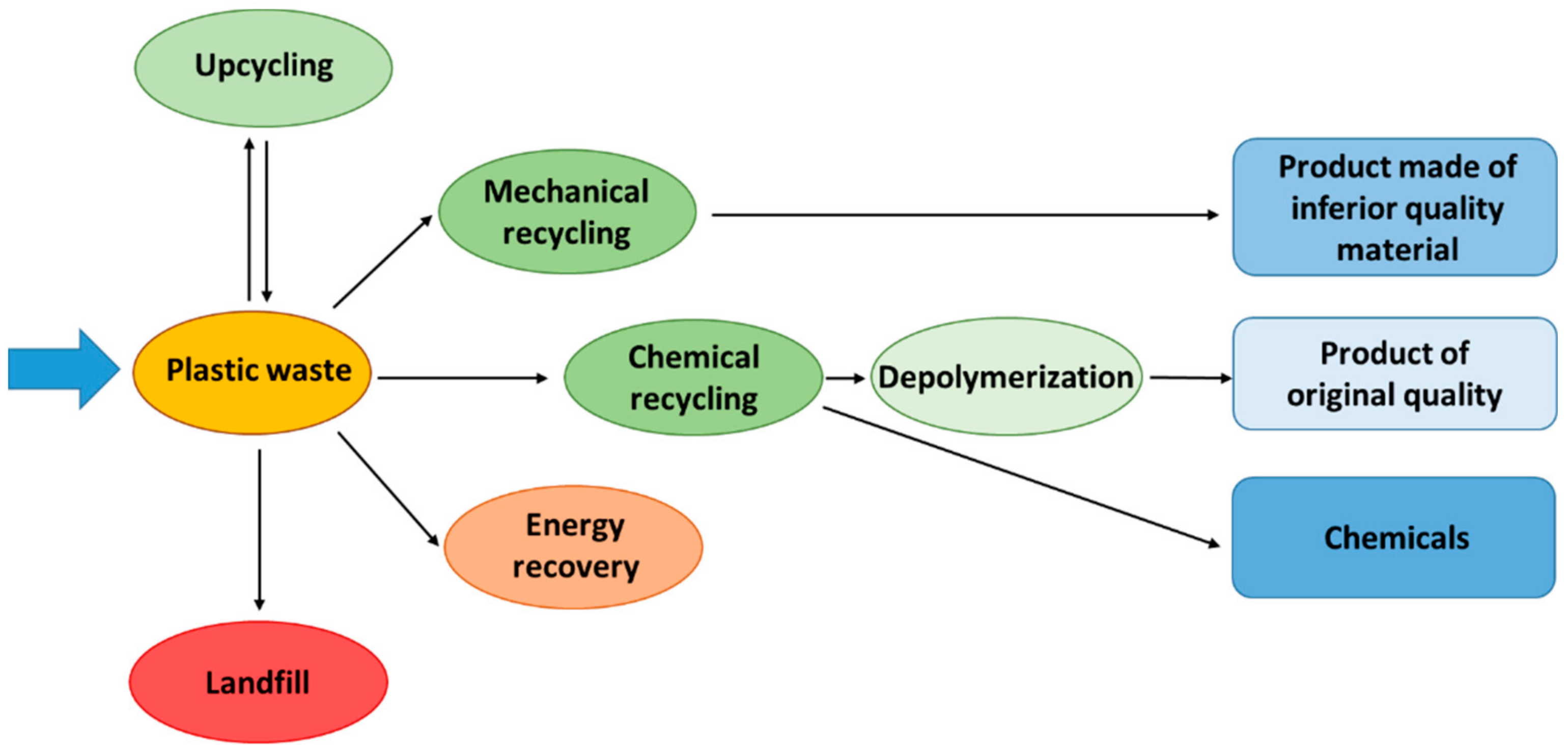

Schematic diagram of major plastic waste management routes, including mechanical recycling, chemical/feedstock recycling, energy recovery and landfill. This supports the discussion of sustainable processing options for polymers. The figure includes some extra detail on specific recycling technologies but the core routes are directly relevant. Source

These materials often accumulate in landfill and contribute to pollution if not properly managed. The specification emphasises understanding a range of processes that address these challenges.

Mechanical Recycling

Mechanical recycling involves sorting, cleaning and remelting plastics to form new polymer products. Although it reduces waste, many polymers degrade slightly during each processing cycle, limiting the number of times they can be reused. Contamination of polymer waste streams also reduces the efficiency and quality of recycled material. This highlights why additional and complementary methods are necessary for sustainable polymer management.

Feedstock (Chemical) Recycling

Feedstock recycling breaks polymers into smaller organic molecules through chemical processes such as pyrolysis or cracking. These smaller molecules can then be used as raw materials for producing new polymers or other chemical products. This method overcomes issues associated with repeated mechanical recycling because the polymer is fully broken down to simpler substances.

Feedstock recycling: The chemical processing of polymers to produce smaller molecules that can act as raw materials for new chemical synthesis.

Feedstock recycling is particularly valuable for mixed or contaminated plastic waste that cannot undergo efficient mechanical recycling. It allows the recovery of high-purity feedstock materials, contributing to a circular approach to polymer use.

Energy Recovery

Another option is energy recovery, where waste polymers are burned under controlled conditions to release thermal energy. Because many polymers are derived from hydrocarbons, they possess high calorific values. The heat released can be used to generate electricity or supply industrial heating. Although this method reduces waste volume significantly, it must be carefully managed to minimise harmful emissions and ensure complete combustion.

Removal of Toxic Additives and Detoxification

Some polymers contain additives such as plasticisers, stabilisers or flame retardants that can pose environmental hazards. Processing methods may include detoxification, which involves removing or neutralising harmful substances before recycling or disposal. These additives can complicate recycling because they may be chemically bound to or mixed within the polymer matrix. Understanding detoxification helps ensure that processing routes remain safe and environmentally sound.

A brief normal sentence follows to maintain coherence before introducing any further formal concepts.

Biodegradable and Photodegradable Polymers

Biodegradable and photodegradable polymers aim to reduce long-term environmental impact by breaking down more readily after disposal.

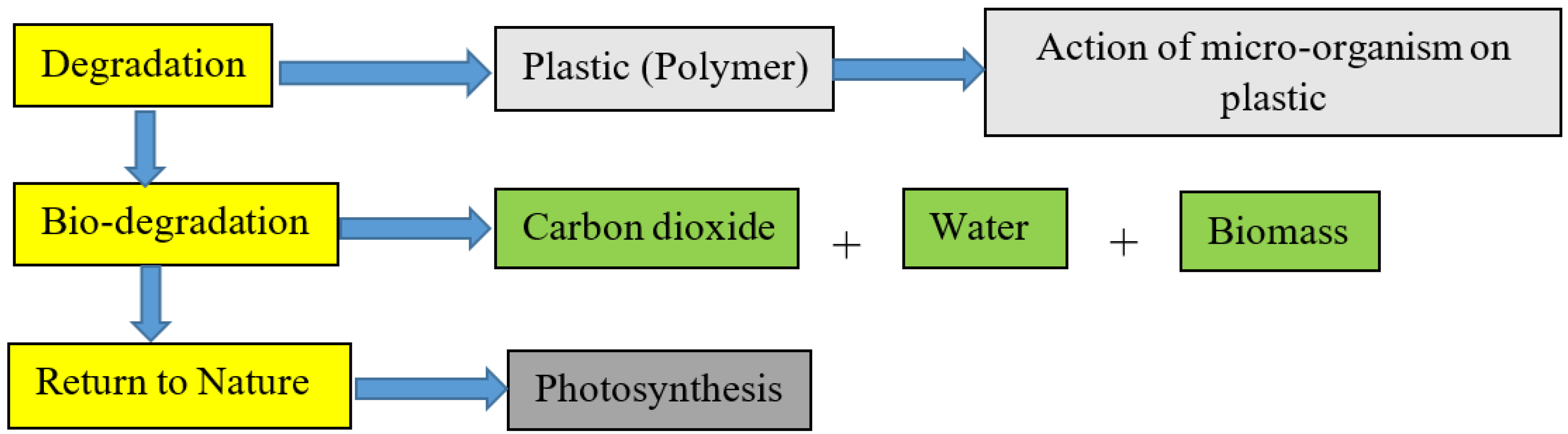

Diagram illustrating biodegradation, where micro-organisms break polymers into carbon dioxide, water and biomass that re-enter natural cycles through photosynthesis. This supports the explanation of biodegradable polymers and their environmental role. The figure contains some detail specific to starch-based films but the core degradation stages are fully relevant. Source

Biodegradable polymers are designed to be decomposed by microorganisms into natural products such as carbon dioxide, water and biomass. Their breakdown rate depends on environmental conditions including temperature, moisture and microbial activity.

Photodegradable polymers incorporate bonds or additives sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) light. When exposed to sunlight, these polymers undergo chain scission, resulting in smaller fragments that degrade more easily. These materials provide alternatives for applications where long-term durability is unnecessary, such as agricultural films or certain packaging.

Biodegradable polymer: A polymer capable of being broken down by living organisms into environmentally benign products.

Biodegradable and photodegradable polymers offer promising solutions, but they require specific conditions for effective degradation. Their use may not fully eliminate environmental concerns unless disposal environments support the necessary biological or photochemical processes.

Designing for Sustainability

Advances in polymer chemistry increasingly focus on sustainable design, which includes selecting monomers from renewable resources, incorporating degradable linkages and developing more efficient recycling technologies. Understanding these strategies enables chemists to create polymer systems with reduced environmental impact while maintaining desired material properties.

FAQ

Chemical recycling is preferred when polymers are too contaminated or degraded for remelting. Polymers with complex additives or mixed waste streams are also more compatible with feedstock methods.

Polymers that can be thermally cracked into useful hydrocarbons, such as poly(ethene) and poly(propene), are particularly suitable because their structure yields valuable feed molecules.

Polymers with strong C–C backbones, high crystallinity or bulky side groups resist degradation because microorganisms and light struggle to access reactive sites.

Hydrophobicity further reduces microbial activity. In contrast, polymers containing ester or amide linkages degrade more readily due to the presence of hydrolysable bonds.

Landfills often lack oxygen, moisture and adequate microbial diversity, all of which are required for efficient biodegradation.

In addition, compacted waste and low temperatures reduce microbial metabolism. As a result, many biodegradable polymers remain intact far longer than intended.

The availability of UV light is the primary factor, meaning degradation is faster in exposed environments and slower in shaded or buried conditions.

Polymer thickness, pigment content and the presence of UV-absorbing additives also influence breakdown rates by either accelerating or blocking UV penetration.

Additives known as pro-oxidants can be incorporated to promote chain scission when exposed to heat or light, creating smaller fragments more accessible to microbes.

Some additives introduce weak bonds into the polymer matrix, lowering activation energy for degradation. Others improve moisture absorption, increasing microbial colonisation and breakdown efficiency.

Practice Questions

Poly(propene) can be recycled through mechanical recycling.

State two limitations of mechanical recycling that affect the quality or usefulness of the recycled polymer.

(2 marks)

Any two of the following:

Loss of polymer strength or quality after repeated heating and remoulding (1 mark)

Contamination of polymer waste reduces effectiveness of recycling (1 mark)

Not all polymers can be mechanically recycled together; separation is required (1 mark)

Limited number of recycling cycles before material becomes unusable (1 mark)

(Max 2 marks)

Biodegradable and photodegradable polymers are increasingly used as alternatives to traditional plastics.

Explain how each type of polymer breaks down and discuss one advantage and one limitation of using degradable polymers in waste management.

(5 marks)

Up to 5 marks awarded as follows:

Explanation of degradation processes

Biodegradable polymers are broken down by microorganisms into carbon dioxide, water and biomass (1 mark)

Photodegradable polymers contain bonds/additives that break under UV light, forming smaller fragments that degrade more easily (1 mark)

Advantages

Reduced long-term environmental impact due to faster breakdown compared with traditional polymers (1 mark)

Limitations

Require specific environmental conditions (microbial activity, moisture, UV light) to degrade effectively; may not break down in landfill (1 mark)

Breakdown into smaller fragments may still cause pollution if conditions are insufficient (1 mark)

(Max 5 marks)