OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe hydrolysis of haloalkanes by aqueous alkali as a nucleophilic substitution forming alcohols; outline practical conditions.’

Hydrolysis of haloalkanes with aqueous alkali is a key nucleophilic substitution reaction in organic chemistry, producing alcohols under specific practical conditions that reveal trends in reactivity.

Hydrolysis of Haloalkanes by Aqueous Alkali

Hydrolysis of haloalkanes using aqueous alkali is an essential reaction in organic synthesis and mechanisms. It involves breaking the carbon–halogen (C–X) bond and replacing the halogen with an –OH group, forming an alcohol. The reaction proceeds through nucleophilic substitution, in which a nucleophile attacks an electron-deficient carbon.

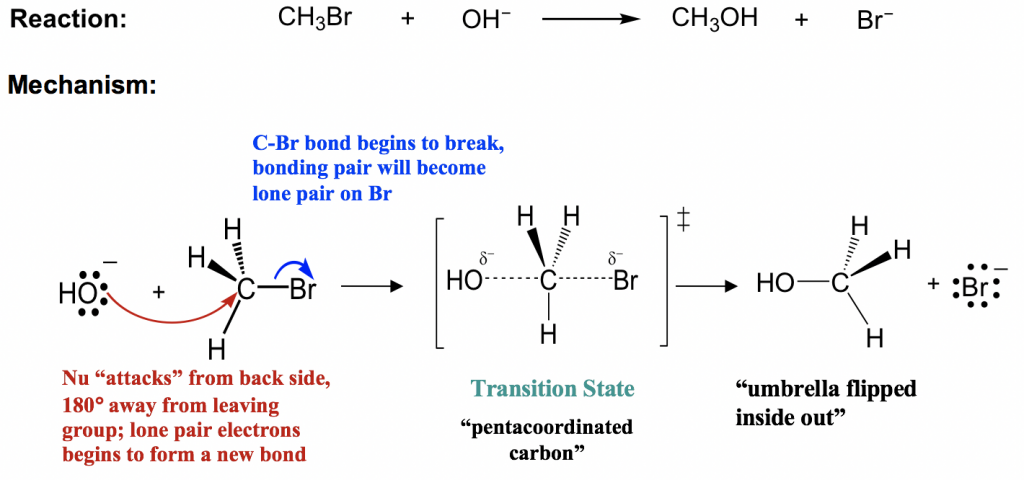

This diagram shows the Sₙ2 nucleophilic substitution of bromomethane by hydroxide ion, forming methanol and bromide. Curly arrows depict electron-pair movement and the breaking and formation of bonds. The image includes a transition state and partial charges, which exceed OCR requirements but aid conceptual understanding. Source

When the term nucleophile is first introduced, provide a definition so students can apply it confidently.

Nucleophile: A species that donates an electron pair to an electron-deficient atom to form a new covalent bond.

This reaction is central to understanding the reactivity of haloalkanes and forms the basis for trends in substitution mechanisms studied later in organic chemistry.

Role of the Aqueous Alkali

Aqueous alkali refers to solutions such as aqueous sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or aqueous potassium hydroxide (KOH). These provide hydroxide ions (OH⁻), which act as the nucleophile. Because the reaction requires aqueous, not alcoholic, conditions, the substitution pathway is favoured.

Key points about aqueous alkali in hydrolysis:

Provides a strong source of OH⁻ ions for nucleophilic attack.

Ensures the substitution reaction dominates rather than elimination.

Helps control temperature and reaction rate during hydrolysis.

The Nucleophilic Substitution Process

Hydrolysis of primary haloalkanes with aqueous alkali occurs via nucleophilic substitution, replacing the halogen with an –OH group. Although the OCR specification does not require a full mechanistic treatment here, students should understand the conceptual steps involved.

The reaction converts:

A haloalkane (R–X)

into

An alcohol (R–OH)

with the halide ion (X⁻) released.

General Hydrolysis of Haloalkanes: R–X + OH⁻ → R–OH + X⁻

R = Alkyl group, no units

X = Halogen atom (Cl, Br, I), no units

In this representation, the hydroxide ion substitutes the halogen directly, producing an alcohol. The reaction is usually carried out under controlled heating conditions to speed up the process.

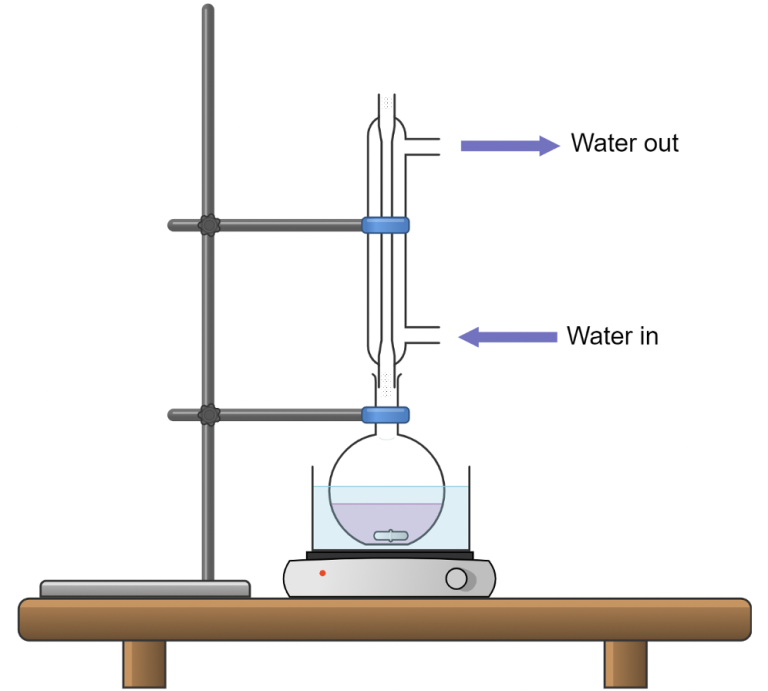

This diagram shows a typical reflux setup with heating and condensation equipment used to prevent the loss of volatile reagents during hydrolysis. Vapours rise, condense in the water-cooled condenser, and return to the flask, allowing sustained heating. The clamp, hotplate, and bath are standard laboratory details beyond the OCR specification. Source

A single clear sentence here helps reinforce how the equation links to practical substitution.

Practical Conditions for Hydrolysis

OCR requires students to be able to outline practical conditions, meaning the key laboratory requirements must be understood. The major conditions for hydrolysis with aqueous alkali include:

Reagent: Aqueous NaOH or KOH.

Solvent environment: Typically a mixture of water and ethanol to ensure the haloalkane dissolves and the nucleophile remains effective.

Heating: Gentle heating under reflux to maintain reaction rate without loss of volatile reactants.

Time: Sufficient heating time to allow complete substitution.

Key laboratory notes:

Reflux prevents loss of unreacted haloalkane.

Ethanol acts as a co-solvent for haloalkanes that are poorly soluble in water.

Using concentrated alkali is not required; moderate concentration is effective.

Factors Influencing the Hydrolysis Process

The hydrolysis rate depends strongly on the C–X bond strength, although trend analysis is formally covered in a later subsubtopic. At this stage, students should recognise that the bond must be broken during hydrolysis, and weaker bonds hydrolyse more readily.

Other influencing factors include:

Haloalkane structure: Primary haloalkanes hydrolyse more cleanly via substitution.

Solvent effects: Aqueous environments stabilise developing charges and promote substitution.

Temperature: Higher temperatures increase kinetic energy and reaction rate.

Observing the Formation of Alcohols

The specification requires that students understand the formation of alcohols, not that they perform analytical confirmation, but knowing how the presence of the product could be verified helps conceptual clarity.

Characteristic indicators that hydrolysis has occurred:

The disappearance of the organic haloalkane layer during heating.

Formation of a homogeneous mixture if the alcohol produced is miscible.

Detection of halide ions (e.g., by precipitation reactions) in further qualitative analysis.

These observations connect the theoretical substitution process to laboratory reality.

Reaction Pathway Summary

To reinforce the OCR specification requirement, the essential process of hydrolysis with aqueous alkali can be summarised using a structured outline:

Step 1: Haloalkane dissolves in aqueous alkali (ethanol often added to aid mixing).

Step 2: OH⁻ nucleophile approaches the δ⁺ carbon of the C–X bond.

Step 3: The C–X bond breaks, releasing a halide ion.

Step 4: The new C–O bond forms, producing an alcohol.

Step 5: Reaction mixture is heated under reflux to ensure completion.

A short sentence here emphasises that these steps align directly with OCR’s requirement to describe hydrolysis and identify the formation of alcohols.

Importance for Organic Synthesis

Hydrolysis of haloalkanes provides a straightforward route to alcohols, which serve as valuable intermediates in synthesis pathways involving oxidation, substitution, and elimination. Understanding this reaction allows students to link functional-group transformations across the organic chemistry modules.

The reaction’s simplicity, reliability, and clear mechanistic logic make it foundational in developing competency in synthetic reasoning for A-Level Chemistry.

FAQ

Polar solvents stabilise charged species, including hydroxide ions and the transition state in nucleophilic substitution.

This increased stabilisation lowers the activation energy, allowing hydrolysis to proceed more quickly.

Water also helps dissolve both the haloalkane (with ethanol added if needed) and the hydroxide ions, enabling more frequent successful collisions.

Increasing hydroxide concentration increases the rate because more nucleophiles are available for collision with the electron-deficient carbon.

At very low concentrations, hydrolysis may become slow enough that competing processes such as elimination (in hot, alcoholic conditions) become more significant.

Aqueous alkali ensures a sufficiently high concentration of hydroxide to favour substitution.

Tertiary haloalkanes form stable carbocations more readily due to electron-donating alkyl groups, so they hydrolyse mainly via a different substitution pathway.

Primary haloalkanes lack this stabilisation, meaning hydroxide must attack directly, consistent with the mechanism relevant to this subsubtopic.

Halide ions can be detected using aqueous silver nitrate after acidification with dilute nitric acid.

Chloride forms a white precipitate.

Bromide forms a cream precipitate.

Iodide forms a yellow precipitate.

These tests confirm that the carbon–halogen bond has been broken during hydrolysis.

Haloalkanes are generally immiscible with water, so ethanol helps dissolve both reactants into a single phase, allowing effective nucleophilic attack.

Ethanol is chosen because it does not interfere significantly with the substitution reaction under aqueous conditions and does not promote elimination as strongly as pure alcoholic solvent.

Practice Questions

A student heats 1-bromopropane with aqueous sodium hydroxide.

State the type of reaction taking place and name the organic product formed.

(2 marks)

Marking points:

Type of reaction: nucleophilic substitution. (1 mark)

Organic product: propan-1-ol. (1 mark)

Haloalkanes undergo hydrolysis when heated with aqueous alkali.

Explain, with reference to nucleophiles and the carbon–halogen bond, how hydrolysis occurs in a primary haloalkane.

Outline the practical conditions required for this reaction and state one observation that indicates the reaction has taken place.

(5 marks)

Marking points:

Identification that hydroxide ions act as nucleophiles that donate an electron pair. (1 mark)

Recognition that the nucleophile attacks the electron-deficient carbon attached to the halogen. (1 mark)

Statement that the carbon–halogen bond breaks, releasing a halide ion and forming an alcohol. (1 mark)

Practical conditions: heating under reflux with aqueous alkali, often in a water/ethanol mixture. (1 mark)

Correct observation, e.g., disappearance of organic layer or detection of halide ions in follow-up tests. (1 mark)