OCR Specification focus:

‘Use water in ethanol with AgNO3 to compare rates of hydrolysis of different carbon–halogen bonds via precipitate formation; relate to bond enthalpy.’

Hydrolysis of haloalkanes using water and silver nitrate provides an essential method to compare reaction rates. Observing silver halide precipitates helps relate mechanisms to carbon–halogen bond enthalpies.

Hydrolysis of Haloalkanes Using Water and Silver Nitrate

Hydrolysis with aqueous silver nitrate in ethanol is a core experimental technique used to compare how quickly different haloalkanes undergo nucleophilic substitution. The method focuses on the relation between precipitate formation, carbon–halogen bond strength, and rate of hydrolysis, as outlined by the OCR specification. Water acts as the nucleophile, while ethanol functions as a mutual solvent to ensure the haloalkane and water mix effectively.

Practical Setup of the Hydrolysis Experiment

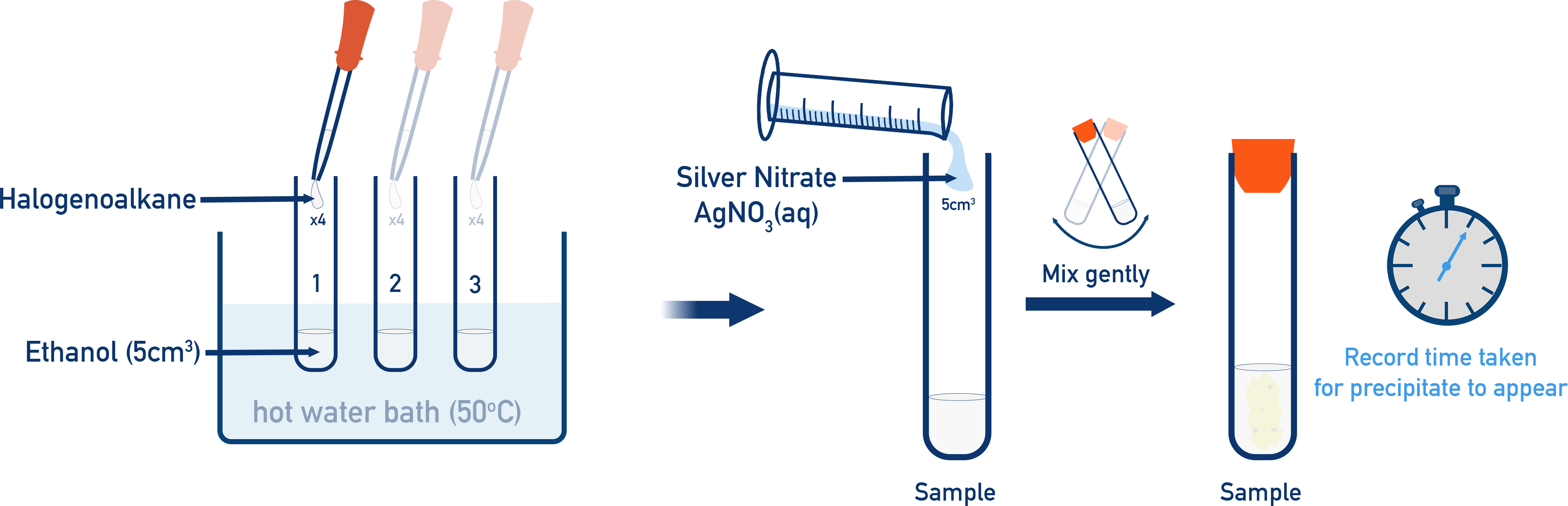

In practice, equal volumes of each haloalkane are warmed with ethanol and aqueous silver nitrate in a thermostated water bath, and the time to first precipitate is recorded.

Experimental set-up for measuring the rate of hydrolysis of haloalkanes using ethanol and aqueous silver nitrate in a 50 °C water bath. Each haloalkane–ethanol mixture is pre‑warmed, then mixed with warm AgNO₃(aq) and gently shaken, and the time for the silver halide precipitate to appear is recorded. The diagram includes additional operational detail beyond the OCR specification but illustrates the same underlying method. Source

Haloalkane Reactivity and the Role of Bond Enthalpy

Hydrolysis rate is primarily determined by the C–X bond enthalpy, where X is the halogen. The weaker the C–X bond, the easier it is for water to attack and substitute the halogen. This leads to measurable differences in reaction speed when comparing chloro-, bromo-, and iodoalkanes.

Bond enthalpy: The energy required to break one mole of a specified bond in the gaseous state.

After this definition is introduced, it becomes clear that compounds with lower bond enthalpies hydrolyse more rapidly. For haloalkanes, the trend follows the order: C–I < C–Br < C–Cl, meaning iodoalkanes hydrolyse fastest and chloroalkanes slowest.

A key learning objective is to connect these enthalpy trends directly to observed laboratory results, making hydrolysis with water and AgNO3 a valuable comparative method.

Practical Setup of the Hydrolysis Experiment

The hydrolysis reaction involves dissolving the haloalkane in ethanol, adding aqueous silver nitrate, and recording the time taken for a silver halide precipitate to appear. The formation of this precipitate indicates that the halide ion has been released from the haloalkane.

Why Ethanol Is Required

Ethanol is a co-solvent, enabling both the haloalkane (organic) and water (aqueous) components to mix thoroughly. Without ethanol, the reagents form separate layers and hydrolysis would be significantly hindered.

Step-by-Step Outline

Students must be able to describe and interpret the procedural steps:

Add a measured volume of haloalkane to ethanol.

Warm gently in a water bath if required.

Add aqueous AgNO3, which provides Ag⁺ ions.

Observe for precipitate formation, indicating halide release.

Compare time taken for each haloalkane tested.

The halide ions formed during hydrolysis react with Ag⁺ to generate distinctive coloured precipitates:

AgCl: white

AgBr: cream

AgI: yellow

Silver chloride forms a white precipitate, silver bromide forms a cream precipitate, and silver iodide forms a yellow precipitate as the halide ions are released during hydrolysis.

Silver halide precipitates formed when chloride, bromide and iodide ions react with aqueous silver ions. From left to right the tubes show AgCl (white), AgBr (cream) and AgI (yellow), matching the colour trends described in the notes. The image focuses on precipitates only and does not depict the ethanol co‑solvent or the hydrolysis step. Source

The Chemical Process During Hydrolysis

The hydrolysis reaction occurs through nucleophilic substitution, where water donates an electron pair to the carbon atom bonded to the halogen. This results in cleavage of the C–X bond and formation of an alcohol.

Nucleophile: An electron-pair donor that attacks an electron-deficient carbon atom.

A normal sentence is inserted here to maintain correct formatting before the next equation block.

Haloalkane Hydrolysis: R–X + H₂O → R–OH + H⁺ + X⁻

R–X = Haloalkane

R–OH = Alcohol formed

X⁻ = Halide ion released

Interpreting Observations and Linking to Bond Enthalpy

The rate at which each haloalkane produces turbidity from precipitate formation mirrors the energy required to break its C–X bond. Lower bond enthalpy leads to faster hydrolysis because less energy is required for the halogen to depart.

Relationship Between Reactivity and Precipitate Formation

Students should understand how observations correspond to theoretical expectations:

Iodoalkanes: Fastest hydrolysis; rapid yellow precipitate.

Bromoalkalkanes: Moderate rate; cream precipitate forms after a short delay.

Chloroalkanes: Slowest; white precipitate may take considerably longer.

This pattern reinforces the specification’s requirement to relate hydrolysis rates to C–X bond enthalpies. Because the C–I bond is weakest, its hydrolysis proceeds most rapidly, aligning directly with the observed experimental results.

Importance of Using Water and AgNO3

This method specifically uses water as the nucleophile, contrasting with hydrolysis using aqueous alkali. The use of AgNO3 is essential because silver ions precipitate halide ions immediately, creating a visible marker for reaction progress. The reaction time becomes a comparative tool rather than a direct measurement of reaction kinetics, yet it reliably demonstrates reactivity trends.

Additional Key Points for Examination

Students should be able to communicate that:

The experiment provides comparative, not absolute, hydrolysis rates.

Precipitate colour identifies the halogen originally present.

Ethanol ensures miscibility and does not participate in the reaction.

The mechanism itself is not required for this subsubtopic, but the concept of nucleophilic substitution remains fundamental.

These concepts together give a comprehensive understanding of hydrolysis with water and AgNO3, directly satisfying OCR A-Level Chemistry learning requirements for this subsubtopic.

FAQ

Ethanol is miscible with both water and haloalkanes, creating a single homogeneous phase. This ensures that water, the nucleophile, has consistent access to the haloalkane molecules.

Other common organic solvents such as hexane or cyclohexane are immiscible with water, which would separate into layers and slow the hydrolysis reaction significantly.

Ethanol also does not interfere chemically with Ag⁺ ions, avoiding unwanted side reactions.

Increasing temperature increases the kinetic energy of molecules, resulting in more frequent and energetic collisions between water molecules and the carbon–halogen bond.

Higher temperature also accelerates the formation of silver halide precipitates, making rate comparisons clearer.

However, excessively high temperatures may cause premature precipitation of Ag⁺ or evaporation of volatile haloalkanes, so controlled heating (normally around 50 °C) is used.

Silver nitrate decomposes slowly in light, forming fine deposits of silver that can contaminate the solution.

Such contamination may cause faint turbidity or unintended precipitates, making it harder to accurately determine the onset of haloalkane hydrolysis.

Keeping the solution in amber bottles or dark storage helps maintain purity for reliable rate comparisons.

Although bond enthalpy is the dominant factor, several secondary factors may affect hydrolysis rates:

Solubility of the haloalkane in the ethanol–water mixture

Steric hindrance around the carbon–halogen bond (more relevant for secondary and tertiary haloalkanes)

Purity of reagents or presence of stabilisers in commercial haloalkane samples

These influences are minor for simple primary haloalkanes but can become more significant with substituted structures.

Initial precipitate formation is easy to observe and provides a consistent comparative point across different haloalkanes.

Monitoring the full extent of the reaction would require quantitative analysis, as precipitate density does not scale linearly with amount of halide produced.

Using the time to first visible precipitate allows rapid, reliable comparison without complex equipment or extended reaction monitoring.

Practice Questions

A student heats 1-bromobutane, 1-chlorobutane and 1-iodobutane separately with ethanol and aqueous silver nitrate.

Explain why a yellow precipitate appears fastest in the reaction mixture containing 1-iodobutane.

(2 marks)

1 mark: The C–I bond has the lowest bond enthalpy / weakest carbon–halogen bond.

1 mark: Therefore, it breaks most easily, so hydrolysis occurs fastest / halide ions are released more quickly.

A student investigates the hydrolysis of three primary haloalkanes using water in ethanol with aqueous silver nitrate.

The student records the time taken for the first appearance of a precipitate in each reaction.

Explain why this method can be used to compare rates of hydrolysis and why the results follow the trend:

1-iodoalkane > 1-bromoalkane > 1-chloroalkane.

In your answer, refer to the role of bond enthalpy, the function of ethanol, and the formation of silver halide precipitates.

(5 marks)

1 mark: Hydrolysis releases halide ions, which react with Ag⁺ to form silver halide precipitates, so precipitate formation indicates the reaction has occurred.

1 mark: Time taken for the precipitate to form acts as a measure of relative hydrolysis rate.

1 mark: Ethanol acts as a co-solvent allowing haloalkane and water to mix; without it, they form separate layers.

1 mark: The C–X bond enthalpy determines hydrolysis rate; the weaker the bond, the faster the nucleophilic attack by water.

1 mark: C–I has the lowest bond enthalpy, then C–Br, then C–Cl, so iodoalkanes hydrolyse fastest and chloroalkanes slowest.