OCR Specification focus:

‘Discuss environmental concerns from organohalogens; recognise benefits of CFCs versus environmental impact and the role of scientific evidence in legislation.’

Alcohols and haloalkanes contribute to several environmental issues, particularly when volatile or persistent compounds enter the atmosphere. This section explores how organohalogens affect environmental systems and how scientific understanding guides regulation and policy development.

Environmental Concerns of Organohalogens

Organohalogens are organic compounds containing halogen atoms such as chlorine, fluorine or bromine. Their widespread use has brought both technological advantages and significant environmental challenges.

Organohalogens: Organic compounds containing at least one halogen atom bonded to a carbon atom.

Organohalogens persist in the environment because the carbon–halogen bond—particularly C–Cl and C–F—is relatively strong. This prevents rapid degradation, allowing the compounds to accumulate and disperse across ecosystems. Many such compounds, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and certain pesticides, have been historically valued for their stability, yet this same stability contributes to long-term ecological effects.

Key environmental issues associated with organohalogens

Persistence and bioaccumulation: Slow degradation means these substances can remain in soils, water and the atmosphere for decades.

Transport through food webs: Lipophilic organohalogens, such as some polyhalogenated pesticides, accumulate in fatty tissue and biomagnify.

Toxicity concerns: Several organohalogen compounds display carcinogenic, teratogenic or endocrine-disrupting properties.

Atmospheric reactions: Some haloalkanes undergo photochemical reactions, releasing radicals that participate in ozone-destroying processes.

Benefits and Drawbacks of CFCs

CFCs were developed in the twentieth century as replacements for toxic refrigerant gases such as ammonia. Their practical advantages led to rapid global adoption.

Benefits that contributed to widespread use

Non-toxic, making them safer than earlier refrigerants.

Non-flammable, reducing industrial and domestic safety risks.

Chemically stable, allowing long equipment lifespans with minimal breakdown.

These same characteristics, however, enabled CFCs to reach the stratosphere intact, where ultraviolet radiation breaks them down into radicals.

Environmental impact of CFCs

Once in the stratosphere, UV photolysis causes C–Cl bond cleavage, generating chlorine radicals (Cl•). These radicals catalyse the destruction of ozone. Although this subsubtopic does not require radical equations, students should recall that a single chlorine radical can destroy thousands of ozone molecules before being removed from the atmosphere.

The depletion of the ozone layer increases transmission of harmful UV-B radiation to Earth’s surface.

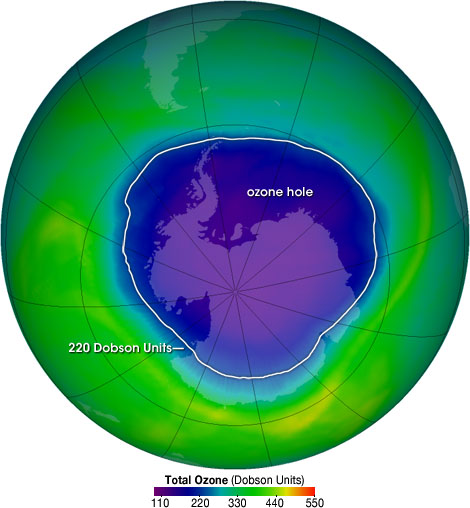

This map shows total column ozone over Antarctica, highlighting the ozone hole where levels drop below 220 Dobson Units. Although it includes detailed data beyond OCR requirements, it visually demonstrates how scientists monitor ozone depletion. Source

Consequences include:

Greater incidence of skin cancer and cataracts in humans.

Reduced phytoplankton productivity, disrupting marine food chains.

Damage to plant tissues, affecting crop yields.

Degradation of materials such as polymers.

One important distinction is that not all organohalogens are equally harmful. Many compounds do not reach or survive in the upper atmosphere, and some are tightly regulated or replaced with safer alternatives.

Scientific Evidence and Environmental Legislation

Role of scientific research

By the 1970s and 1980s, atmospheric studies demonstrated declining ozone concentrations over Antarctica. Correlations with CFC emissions, supported by laboratory data and atmospheric modelling, provided strong evidence of their role in ozone depletion.

Scientific validation drives policy formation. Data must be reproducible, peer-reviewed and internationally recognised to underpin global agreements. Atmospheric chemists, remote sensing technologies and long-term monitoring stations all contributed to confirming the mechanism of ozone loss and the contribution of CFCs.

A key lesson for A-Level Chemistry is how chemical evidence informs environmental decision-making, showing the direct link between chemistry knowledge and public policy.

The Montreal Protocol and regulatory action

In 1987, global consensus led to the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty that phased out production of CFCs and several other ozone-depleting substances.

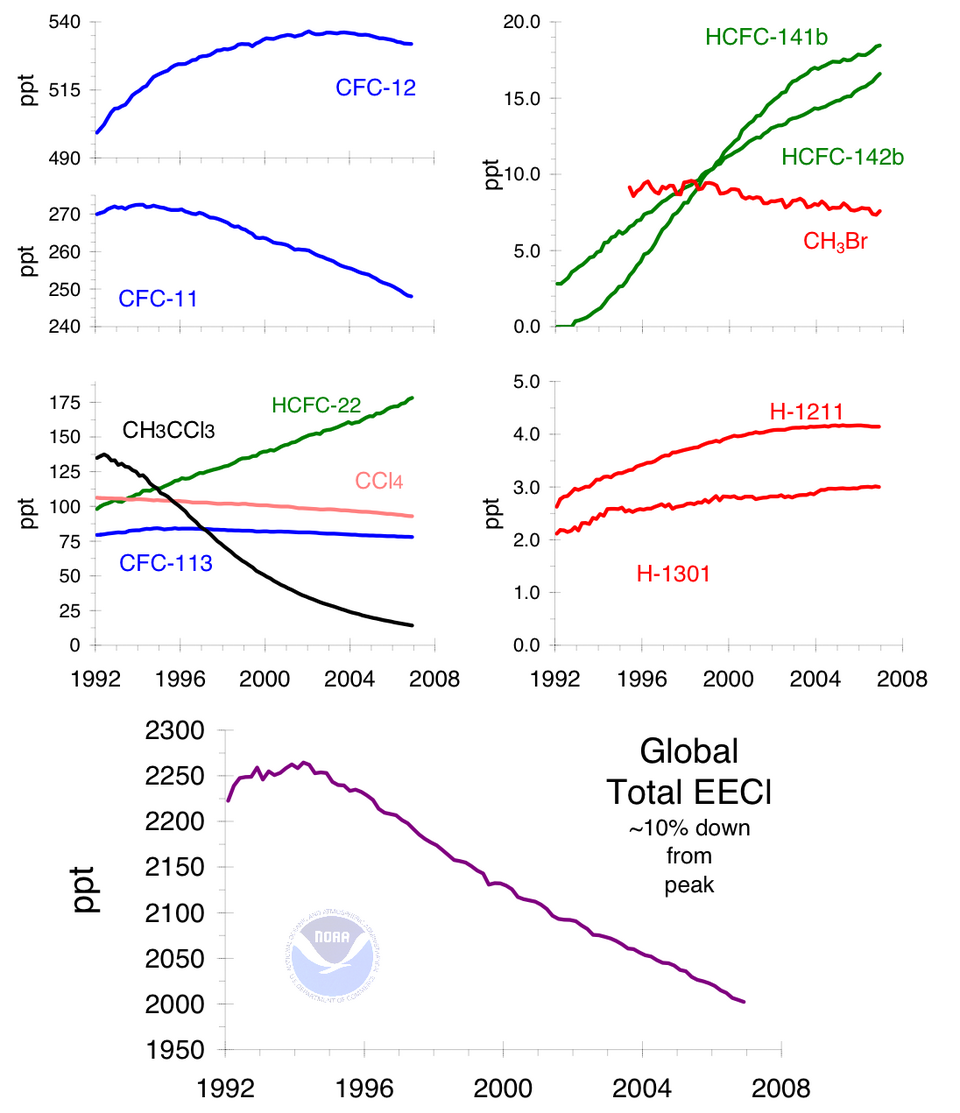

This figure displays atmospheric trends of major ozone‑depleting gases and the combined equivalent effective chlorine. The downward trend illustrates the impact of Montreal Protocol regulations, though the multiple subgraphs include more compounds than those specified by OCR. Source

This remains a landmark example of science-driven cooperation. Subsequent amendments strengthened restrictions and introduced timetables for eliminating additional halogenated compounds.

Key features of the regulatory approach include:

Precautionary action: Limiting substances even when some uncertainties remained.

Development of alternatives: Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) initially replaced CFCs, though later concerns about global warming potential prompted further evaluation.

Ongoing monitoring: Satellite data and atmospheric measurements continue to check recovery progress of the ozone layer.

Broader Environmental Considerations

Apart from ozone depletion, organohalogens raise additional environmental concerns that extend beyond the atmosphere.

Climate impact

Some haloalkanes, including HFCs and HCFCs, are potent greenhouse gases. Their strong absorption of infrared radiation contributes to global warming. Recognition of these effects has motivated development of newer refrigerants with lower global warming potential.

Aquatic and terrestrial contamination

Haloorganics used in industry or agriculture may enter water systems, leading to contamination of rivers and groundwater. These pollutants resist biodegradation and may require advanced treatment processes such as activated carbon filtration or specialised oxidation methods.

Waste management challenges

Incineration of halogenated waste can produce toxic by-products, including hydrogen halides and dioxins, unless conducted under controlled high-temperature conditions. This reinforces the need for strict disposal guidelines.

Balancing benefits with risks

Regulation does not imply that all organohalogens must be eliminated. These compounds play crucial roles in medicine, materials science and electronics. The challenge is to balance societal benefits with environmental integrity. Policies now encourage:

Safer molecular design (e.g., shorter atmospheric lifetimes).

Responsible use and containment.

Replacement of hazardous compounds with greener alternatives.

Improved chemical monitoring and environmental assessment.

Understanding these considerations equips students to evaluate the role of organohalogens in modern society while interpreting how chemical knowledge shapes environmental action.

FAQ

Organohalogens often have low polarity and high chemical stability, meaning they do not break down easily in water or soil.

Their volatility enables some of them, such as CFCs, to diffuse through the atmosphere until they reach the stratosphere.

Persistent compounds also tend to dissolve into fats rather than water, increasing their tendency to bioaccumulate in living organisms.

Fluorine radicals react quickly with water and form HF, removing them from the radical cycle.

Chlorine radicals, however, remain active for far longer and participate in repeated catalytic destruction of ozone.

This difference in atmospheric behaviour explains why CFCs containing chlorine, rather than fluorine, are the primary concern for ozone loss.

Safer alternatives are designed to have shorter atmospheric lifetimes so they degrade before reaching the stratosphere.

They may form radicals that rapidly react with common atmospheric species, limiting long-range environmental impact.

Many contain hydrogen atoms, allowing breakdown by lower-atmosphere reactions that traditional CFCs resist.

Monitoring stations regularly measure the concentration of halogen-containing gases in the troposphere and stratosphere.

Satellite systems track global ozone distribution and detect regional depletion patterns.

These datasets are combined with computer models to evaluate trends, predict recovery and detect the effects of new industrial chemicals.

Some organohalogens used in agriculture and manufacturing dissolve into fatty tissues rather than water.

As they persist, they build up in organisms and become more concentrated at higher trophic levels.

This can expose predators, including humans, to levels far greater than found in the environment, increasing potential health risks.

Practice Questions

Explain why chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) pose an environmental risk despite being chemically stable in the lower atmosphere.

(2 marks)

1 mark – CFCs reach the stratosphere because they are unreactive/chemically stable in the lower atmosphere.

1 mark – UV radiation breaks CFCs to form chlorine radicals that catalyse ozone depletion.

Discuss how scientific evidence led to international legislation controlling the use of organohalogen compounds such as CFCs. In your answer, refer to:

the type of data scientists collected

how this evidence supported the proposed mechanism of ozone depletion

how this resulted in policy actions such as the Montreal Protocol.

(5 marks)

Award marks for any five valid points:

1 mark – Scientists collected atmospheric measurements showing declining ozone concentrations, particularly over Antarctica.

1 mark – Laboratory studies demonstrated that UV photolysis of CFCs releases chlorine radicals.

1 mark – Evidence linked these radicals to catalytic cycles that destroy ozone.

1 mark – Modelling and monitoring data supported the relationship between CFC emissions and ozone depletion.

1 mark – This scientific consensus prompted international action, leading to the Montreal Protocol and later amendments regulating CFCs and related organohalogens.