OCR Specification focus:

‘Devise two-stage synthetic routes between functional groups encountered so far, applying given or familiar transformations to reach a target molecule.’

Organic synthesis involves planning logical reaction sequences to convert one functional group into another using known chemical transformations efficiently and selectively under appropriate conditions.

Understanding Two-Stage Synthetic Routes

Two-stage synthetic routes involve converting a starting functional group into a target functional group through two consecutive reactions, each using reagents and conditions specified within the OCR A-Level Chemistry syllabus. Students are expected to recognise suitable intermediates and select reactions already encountered in Module 4.

A successful route requires:

Identification of the starting functional group

Identification of the target functional group

Selection of a sensible intermediate that can be formed and then transformed

Use of appropriate reagents and conditions for each stage

What Is a Synthetic Route?

Synthetic route: A planned sequence of chemical reactions used to convert a starting compound into a desired product via one or more intermediates.

Between each stage, the functional group must change in a chemically realistic way. Reactions must be familiar and syllabus-approved, such as oxidation, reduction, substitution, elimination, or hydrolysis.

Identifying Starting Materials and Targets

The first step in devising a route is analysing the functional groups present in both the starting compound and the target molecule. This determines what transformations are needed.

Key considerations include:

Whether the carbon skeleton stays the same

Whether oxidation level increases or decreases

Whether a functional group needs to be replaced or rearranged

For example:

Alcohol → carboxylic acid involves oxidation

Haloalkane → alcohol involves hydrolysis

Alcohol → alkene involves elimination

Recognising these links allows the selection of an appropriate intermediate that bridges the two stages.

Choosing a Suitable Intermediate

The intermediate must be:

A compound that can realistically be formed from the starting material

Capable of being converted into the final product using known reactions

Common intermediates include:

Alcohols (central to many routes)

Haloalkanes

Alkenes

Aldehydes or ketones

Alcohols are especially important because they can undergo oxidation, substitution, elimination, and combustion, making them versatile intermediates.

Before choosing reagents, plan the route by working backwards from the target functional group to a plausible intermediate, then convert that intermediate to the required starting material.

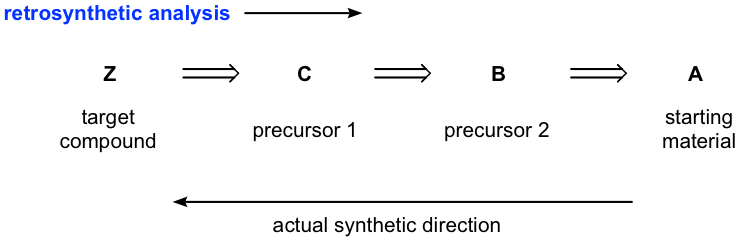

This diagram illustrates retrosynthetic analysis, where the target molecule is simplified stepwise to plausible precursors. The forward synthesis is then written in the opposite direction using appropriate reagents and conditions. Source

Applying Familiar Transformations

Only transformations already encountered in the specification should be used. These include:

Oxidation Reactions

Primary alcohols oxidised to aldehydes or carboxylic acids

Secondary alcohols oxidised to ketones

Tertiary alcohols resist oxidation

Oxidation reactions often use acidified potassium dichromate(VI), with conditions determining the final product.

Substitution Reactions

Alcohols converted to haloalkanes using halide ions and acid

Haloalkanes hydrolysed to alcohols using aqueous alkali

These reactions allow movement between alcohols and haloalkanes depending on the desired outcome.

Elimination Reactions

Alcohols dehydrated to form alkenes

Requires heat and an acid catalyst such as phosphoric acid

Elimination is useful when introducing unsaturation before further reactions.

One common two-stage pattern is alcohol → alkene → product, using dehydration to create an alkene intermediate that can be transformed in the next step.

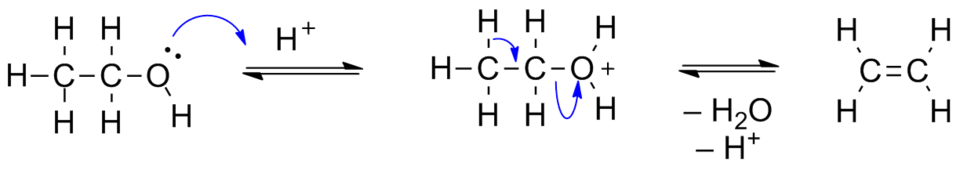

This scheme shows dehydration of an alcohol to form an alkene under acidic conditions. Curly arrows indicating electron movement are included as extra detail beyond OCR requirements, but the functional group change is the key focus. Source

Writing Two-Stage Routes Clearly

Routes should be written as two separate steps, each clearly labelled with reagents and conditions. The intermediate must be shown or named between the steps.

For clarity:

Each stage should show one reaction arrow

Reagents should be written above the arrow

Conditions such as heat, reflux, or catalyst should be included where required

Students are not required to include mechanisms unless explicitly asked elsewhere.

Avoiding Common Errors

When devising routes, several common mistakes should be avoided:

Using reactions not in the specification

Attempting to change more than one functional group in a single step

Choosing an intermediate that cannot undergo the second reaction

Forgetting essential conditions such as aqueous or alcoholic solvents

Routes must be chemically sensible and based on realistic laboratory chemistry.

Linking Routes to Functional Group Properties

Understanding functional group behaviour helps justify route choices. For example:

Alcohols are reactive due to the polar O–H bond

Haloalkanes undergo nucleophilic substitution because of the polar C–X bond

Alkenes undergo addition reactions due to the C=C bond

These properties explain why certain transformations are feasible within two stages.

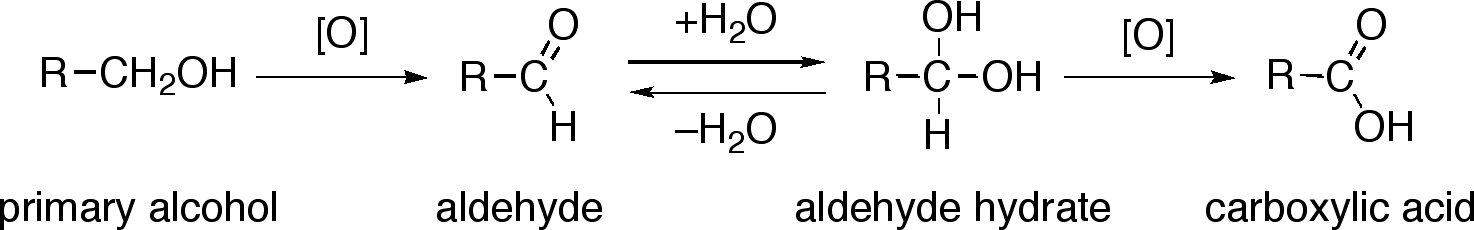

In two-stage planning, oxidation can be used to move between primary alcohols, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids, with conditions chosen to control how far oxidation proceeds.

This diagram summarises oxidation of a primary alcohol through an aldehyde to a carboxylic acid. The aldehyde hydrate shown is extra detail beyond OCR requirements but helps explain why aqueous conditions allow further oxidation. Source

Using Given Information in Assessments

In examinations, additional reactions or reagents may be provided. These can be incorporated into routes even if not memorised, provided they are clearly stated in the question.

Students should:

Carefully read all supplied reaction information

Integrate new reactions logically with known transformations

Maintain clear, stepwise routes with justified intermediates

This skill demonstrates an ability to apply chemical knowledge flexibly rather than relying on memorisation alone.

Scope of Two-Stage Routes in OCR Chemistry

Two-stage routes are limited to functional groups encountered so far in Module 4, including alcohols, haloalkanes, alkenes, aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids. More complex synthesis planning is developed later but builds directly on these foundational skills.

Mastering two-stage routes strengthens understanding of reaction chemistry, reinforces functional group interconversion, and prepares students for integrated organic synthesis questions across the specification.

FAQ

The decision depends on which functional group must be present for the second reaction to occur.

If a later reaction requires an alcohol (e.g. oxidation or dehydration), substitution to form the alcohol must come first.

If oxidation would destroy or prevent a later substitution, oxidation should be delayed until the final stage.

Always choose the order that keeps the intermediate chemically stable and reactive under the required conditions.

Alcohols are highly versatile and can undergo several syllabus-approved reactions.

They can:

Be oxidised to aldehydes, ketones, or carboxylic acids

Be dehydrated to form alkenes

Be substituted to form haloalkanes

This flexibility makes alcohols suitable “junction points” when planning efficient two-stage routes.

Yes, more than one valid route may exist.

For example, a carboxylic acid could be formed via:

Alcohol → aldehyde → carboxylic acid

Haloalkane → alcohol → carboxylic acid

As long as both steps use known reactions and correct conditions, alternative intermediates are acceptable in exam answers.

Reaction conditions determine how far oxidation proceeds.

For primary alcohols:

Gentle heating and distillation favour aldehyde formation

Heating under reflux promotes further oxidation to carboxylic acids

Incorrect conditions may lead to over-oxidation, producing the wrong final functional group.

Reagents should be specific enough to show clear chemical understanding.

For example:

“Aqueous sodium hydroxide” is better than “alkali”

“Acidified potassium dichromate(VI)” is better than “oxidising agent”

Precise naming helps examiners identify the intended reaction and award marks accurately.

Practice Questions

A student wants to convert a primary alcohol into a carboxylic acid using a two-stage synthetic route.

(a) Name a suitable intermediate formed in the first stage.

(b) State the type of reaction used in the second stage to form the carboxylic acid.

(2 marks)

(a) Suitable intermediate named

Aldehyde

Award 1 mark

(b) Correct reaction type stated

Oxidation

Award 1 mark

Devise a two-stage synthetic route to convert a haloalkane into a carboxylic acid.

Your answer should:

Name the intermediate formed

State the reagents and conditions used in each stage

Identify the type of reaction occurring in each stage

No reaction mechanisms are required.

(5 marks)

Stage 1: Conversion of haloalkane to alcohol

Correct intermediate identified as an alcohol

Award 1 markCorrect reagents and conditions stated (e.g. aqueous sodium hydroxide, heat/reflux)

Award 1 markReaction type correctly identified as nucleophilic substitution or hydrolysis

Award 1 mark

Stage 2: Conversion of alcohol to carboxylic acid

Correct reagents and conditions stated (e.g. acidified potassium dichromate(VI), heat under reflux)

Award 1 markReaction type correctly identified as oxidation

Award 1 mark

Maximum 5 marks